Moscow, city of fire and ice

- Share via

MOSCOW — Once I came to Moscow to cover an urban ballooning expedition. In winter. But when the balloonists came face to frigid, wind-lashed face with the winter here — well, we never got off the ground.

And so, as icy gales scoured the city, I strolled near the Moskva River until I faced a vast, low-hovering cloud, lighted from within, scented with chlorine and cigarettes. Occasionally, a near-naked Muscovite would emerge, dripping, and wander off to look for a towel and his pants.

This, I learned, was central Moscow’s only heated outdoor public swimming pool, full of sloshing Russians. Later, I heard it had once been the site of a church, and there were rumors of some kind of curse. But to me, in early 1990, with the Soviet Union on the verge of collapse and Moscow full of features that I couldn’t begin to understand, this one made me smile. I wanted to jump in — another idea that never got off the ground.

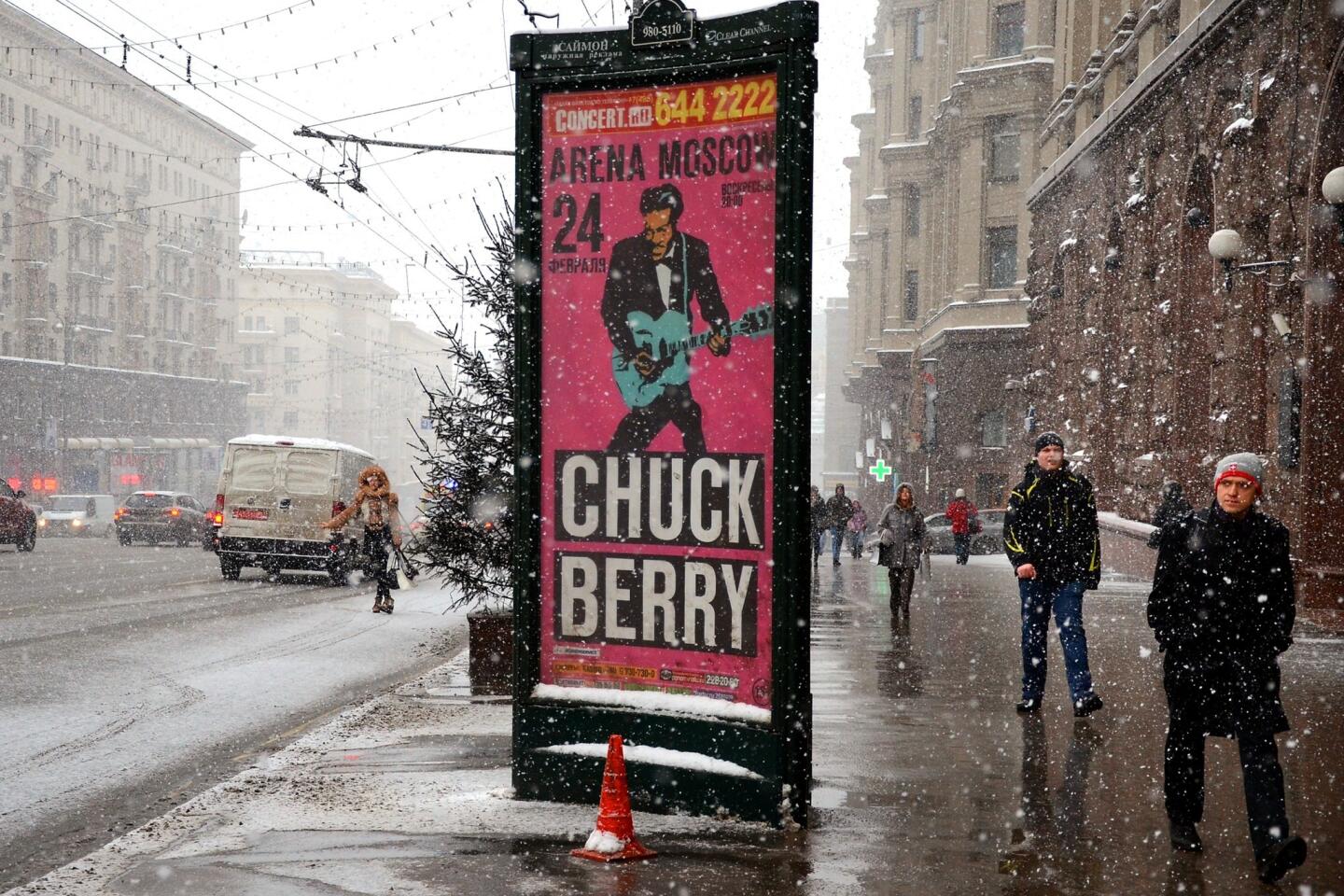

Then last winter, on my way to a pre-Olympics assignment in Sochi, Russia, I landed again in Moscow, pelted by snow, numbed by wind. It was different. It was better.

For a tourist, anyway. Moscow, draped in snow and twinkling with unevenly distributed material wealth, is an amazing spectacle, whether or not you came of age during the Cold War. Besides all the new money, the westward cultural tilt and the wacky theme restaurants that have turned up in post-Soviet days, the city remains rich with architecture and art that go back centuries. And the Muscovites are so good at winter! One afternoon I watched a woman in a fur hat cross an icy sidewalk, hop over a slushy gutter and hail a taxi with all the elegance of a figure skater on a freshly prepped rink.

This is not to say that Russia is easy in any season. Many travelers are repelled by the anti-gay “propaganda” law adopted by the country’s legislators in 2013. Others are wary of terrorism in the run-up to the Olympics. More on the law and terrorism at https://www.lat.ms/1hFpU3u.

Then there’s the red tape. In trip planning, I heard nyet so often that I had to visit San Francisco (to get my journalist visa in time from the Russian Consulate there) and Beverly Hills (because Aeroflot would let me change my ticket only if I came to its office).

And then, once you arrive, you confront some of Europe’s stiffest prices and a legion of cashiers and waiters who want nothing to do with your American Express card.

Still, if you go, wintry Moscow will open your eyes. Before I update you on the swimming pool (yes, I went back) and before the Olympics begin in Sochi on Friday (and run through Feb. 23), here are a few questions and answers about a city where no snow-making equipment has ever been necessary. As we go, bear in mind what my translator and guide, Svetlana Gaikovich, told me on our first day:

“Moscow is not Russia. Moscow is a small country within Russia. A showcase.”

Do I have to start in Red Square like every other tourist?

Yes. Stand out front and gawk at the domes and turrets and statues of St. Basil’s Cathedral, which dates to the 16th century. Pay for a tour behind the walls of the Kremlin next door, where three more cathedrals wait, including the 15th century Assumption Cathedral, whose interior — martyrs on the pillars, Christ on the iconostasis — makes St. Basil’s gaudy exterior look like a blank slate.

Across the square from the Kremlin you have GUM, an arcade-style, three-level, 1890s department store formerly run by the government. Now GUM is a retail fantasy land, privately owned since 2005 by a group led by the ubiquitous luxury retailer Bosco di Ciliegi.

Only an oligarch could pay the prices at the GUM Tiffany and Burberry shops, but that’s not so different from Fifth Avenue in New York. And the holiday lights and displays are about as remarkable. What you won’t find on Fifth Avenue is GUM’s Stolovaya 57, a bustling restaurant that mimics a 1957 Soviet factory cafeteria all the way down to its plates of “herring in a fur coat.” (That’s herring and potatoes with beets and carrots. Better than it sounds.)

If you can afford it, sleep in one of the new or redone hotels near the square. Since 2007, Ritz-Carlton has been on a site once dominated by a grim Intourist hotel. In late 2011, the Intercontinental Hotel Tverskaya replaced the former Minsk Hotel. The old Hotel Moskva, a landmark that was built in the 1930s and razed in about 2004, has been replaced by a new Hotel Moskva, run by Four Seasons, due to open in mid-2014.

I stayed at the Hotel Metropol, an Art Nouveau landmark built in 1901. Every day, heading down to fortify myself at the breakfast buffet, I passed pictures of previous guests such as Vladimir Lenin, George Bernard Shaw, Bertolt Brecht and Michael Jackson.

Why am I hearing Louis Armstrong?

That’s the sound of the Red Square winter skating rink, a block from the Metropol. “What a Wonderful World” was playing as I stepped up. In the center of the ice, a couple was kissing. (All this, by the way, is two snowball tosses from Lenin’s Mausoleum.)

But don’t do all your skating in Red Square. Head instead to Gorky Park, which is so much more than a 1981 detective novel by Martin Cruz Smith. It’s 300 acres along the river, redesigned in 2011 to banish that bedraggled-old-fairgrounds feeling. In winter there are ice sculptures, light displays, playfully decorated Georgian food huts, hockey games, art installations, wedding parties and mini-slopes for snowboarders. The skating rink and linked paths cover more than 4 acres. If there’s a better place to insinuate yourself among hordes of happy Russians, I haven’t found it yet.

Will they keep me warm?

No. Your warmest option in Moscow is the ornately appointed Sanduny Baths, the oldest bathhouse in the city, about a mile from Red Square, where I half-melted a pair of glasses. (It would have been wiser to leave them outside the sauna.)

Another option is an 18th century mansion now known as Café Pushkin. It used to be a pharmacist’s home and office. The upstairs “library” area, appointed with bookshelves, globes and waiters who hover, is where plutocrats break bread with politicians. My lunch there was the biggest splurge of my trip (almost $150 for two people), but the mushroom soup and salmon-stuffed dumplings were terrific.

You said something about art. It’s not all icons, is it?

Well, icons are basically all Russian artists did from the 11th to 18th centuries, so you’ll see plenty at the State Tretyakov Gallery, along with brilliant later portraits and landscapes. In the New Tretyakov, at a separate location, there’s a statue garden of cast-off Soviet heroes (many Lenins, one Brezhnev, no Stalins).

But the surprise, art-wise, is Red October, a bohemian neighborhood that has arisen since 2006 in a former Red October chocolate factory across the river from the Kremlin. Tenants include the Lumière Brothers Center for Photography (opened 2010); Red October Gallery (opened 2012); Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design; and several nightclubs and restaurants, including a hipster café called Produkti, whose tattooed and perforated patrons could slouch into any coffeehouse in Eagle Rock.

Look up. What’s that enormous metal thing rising over Red October and the river?

It’s a sculpture of Peter the Great, father of the Russian navy and czar of Russia from 1682 to 1725. It’s taller than the Statue of Liberty (more than 300 feet) and was unveiled in 1997. The nicest thing I can say is that it’s really big.

And across the river ... . Wait. What happened to the big, round pool?

Remember how we used to hear of Soviet big shots appearing and disappearing from official photos as their fortunes rose and fell? Well, before it ever held a swimming pool, that plot of land held the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, completed in 1883 to commemorate Russia’s resilience during Napoleon’s attack and retreat in the early 19th century. It was a central figure in the Moscow skyline, the exterior topped by five golden domes, the interior walls crowded with frescoes.

Then came the revolution. Russia’s atheist government blew up the cathedral on Dec. 5, 1931 — leveled it — and started laying plans to raise a statue of Vladimir Lenin 1,600 feet tall — big enough to make today’s Peter the Great look like a Disney dwarf.

But then came the Great Patriotic War (World War II), which killed more than 20 million Russians. By the time it was over, nobody was ready to put up a 1,600-foot Lenin. And so in 1958, that massive pre-construction hole in the ground was converted into a big, round swimming pool — the pool I saw in 1990.

The end. Right?

Wrong. In the early 1990s, as the Soviet Union was falling apart, church leaders started lobbying to have the pool filled in and the church rebuilt. Finally the government said yes. Donations poured in. Construction went up. By 2000 the cathedral was born again, 338 feet tall.

The snow was falling hard and fast when I arrived at the site last winter. I spent a minute outside, sniffing for chlorine, before stepping inside under the vibrant frescoes and those five golden domes.

Clearly, Russia’s leaders and the Russian Orthodox Church are getting along better these days. In fact, that’s why the women of Pussy Riot staged their protest/prayer/performance in this church on Feb. 21, 2012 — to decry Vladimir Putin’s power.

I’m staying out of that conversation. For a stranger who drops by every 24 years or so, the cathedral is striking enough as a 338-foot-high reminder of how far a society can shift in a single generation — and then shift again. Who can be sure what this real estate will stand for, spiritually, culturally, politically, in another generation?

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.