Speed touring India’s Taj Mahal & Golden Triangle

- Share via

Agra, India — The sane traveler makes a simple calculation when planning a getaway: The longer it takes to get there, the longer the stay required to make it worthwhile. By that definition, my friends and I are not sane travelers. ¶ We did Peru’s Machu Picchu over a long weekend in 2003. We used another long weekend in 2005 to see Iguazú Falls from the Argentine and Brazilian sides. We trekked to the ancient city of Petra in Jordan last year — and were back home by week’s end.

There was no place in the world, we figured, that couldn’t be conquered in a few days by a group of determined middle-aged suburban fathers with wanderlust, carry-on luggage and the ability to power through jet lag.

No place, that is, except perhaps India.

Oh, how we wanted to see the Taj Mahal. We talked about it frequently, over drinks in South America, in the Middle East and at our homes in the foothills near Los Angeles. But even with the best airline connections, a fast driver and little sleep, the Taj was a good 36 hours of travel from Los Angeles. And even if we were crazy enough to do it all in less than a week, would we even remember it?

In late December, one of my fellow travelers sent around an e-mail challenge: “I have a taste for tandoori. Are we on?”

It was all the push we needed.

Our plan was to explore India’s Golden Triangle, the 430-mile tourist route from Delhi to Jaipur to the Taj Mahal in Agra and back to Delhi. With air travel, we would cover about 14,430 miles and spend five days on the ground.

Along for the ride were my regular travel companions, Richard Goetz and Steve Stathatos, and another friend from our first trip to Peru, Stan Blumenfeld. Our trip had the hearty endorsement of our spouses, none of whom wanted to endure such a long journey at such a quick pace.

Right away, a glitch

As we left for the airport on a Sunday morning in late February, we went through our usual preflight competition to determine who had squeezed the most stuff into the smallest bag. Stan won, though just barely; all of us easily fell within the carry-on limit.

On arriving at the American Airlines terminal at LAX shortly after 7 a.m., we got a sharp reminder of how vulnerable a quick journey is to even a small hiccup. The terminal was a nightmare of unmoving queues, due to weather cancellations the previous day.

Passengers like us, with carry-on baggage and confirmed tickets, had to wait with those passengers rebooking and buying tickets. We found a supervisor, but by then our flight had left. She booked us standby on the next flight to Chicago — our last chance to make our connection to New Delhi. Steve called his travel agent, and, as if by magic, an airport fixer named Anna appeared at our gate to make sure all four of us cleared the wait list. As we boarded, Steve gave Anna a spontaneous, grateful hug.

As our plane descended toward a night landing in Delhi, the pilot spoke over the intercom. The weather in Delhi, he said, was 72 degrees and “smoke.” Like the landing, his forecast was right on target — a mild night and air thick with smoke from cooking fires.

We headed straight for the Imperial, approaching the landmark hotel on a private driveway lined with two dozen king palms. The hotel was built in the waning days of British rule in the 1930s, and Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and Lord Mountbatten met frequently there to discuss the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

We settled into soft leather chairs in the 1911 Bar (named for the year that King George V declared his plan to move the capital of India from Calcutta to a “new” Delhi) and gazed at the stained-glass roof, feeling a bit wobbly from the trek. Tall, frosty glasses of beer steadied us, though.

We were up early the first morning to meet our driver, Prakash Chandra, and city guide, and soon our comfortable, six-seat SUV was nosing its way into the cacophonous streets of Delhi. As one of my companions wryly observed, the honking horn seemed to be India’s national anthem.

When we were arranging our trip, a tour operator quoted us $3,150 per person for a ground package matching our itinerary. But we did the trip for about $1,500 per person, using a Los Angeles travel agent to book the same hotels directly and a Delhi travel agent, recommended by a friend, to book the car, driver and guides.

Our first stop was Old Delhi and Jama Masjid, India’s largest mosque, built in 1656. We climbed a narrow, circular stairway to the top of one of the minarets, marveling at the view of the Red Fort, the 17th century palace built by Shah Jahan, and the merchants selling raw lamb from street-side stands in Old Delhi below.

We emerged from the mosque and hopped onto waiting bicycle rickshaws, and our drivers weaved through the Spice Market, expertly — but barely — avoiding wooden carts loaded with rice, spices and flowers — the sustenance of this city of 14 million.

It was a challenge to snap photographs of one another as our rickshaws dodged traffic. We ended up with excellent photos of the backs of our heads; I later dubbed our group “The Bald Spots.”

We had picked a good time of year to visit Delhi, before the punishing heat of spring, which is followed by the summer monsoons. The weather in late February was cool at night and in the 60s and 70s during the day.

As the afternoon warmed up, we took a walk through India’s bloody history, starting with Gandhi Smriti, the colonial house where Gandhi was staying in 1948 when he was assassinated by a lone gunman as he walked to prayers. Gandhi’s last steps are marked on a narrow path through the quiet garden.

Then we headed to Indira Gandhi‘s home, where the prime minister was shot in 1984 by two of her Sikh bodyguards while walking to an interview. The spot where she fell, beneath a canopy of trees, is marked behind a gate on the compound.

The simple white bungalow is now a museum, crowded with Indian tourists when we visited, where one can see her office and sitting room as well as the sari and shoes she was wearing when she died. Also on display are the sneakers and tattered tunic her son Rajiv was wearing when he was killed by a female suicide bomber in 1991.

By evening we had reached information overload and we sleepwalked through a meal at the trendy restaurant Veda, near Connaught Place, the former commercial district of the Raj. We retired to our rooms, pulled up the Porthault linen and quilted bedspreads and fell asleep.

Closer look at Delhi

We approached our second day in Delhi with a little less ambition and thus began to absorb a sense of the city’s split personality.

There were roundabouts and broad boulevards but also narrow, winding streets. The roadways were choked with natural gas-powered motorized rickshaws and buses, bicycles, SUVs and little Ambassador cars functioning as taxis but also ferrying diplomats and, in one case, a three-star general. The passing scene was no less fascinating: Squatters in tents made of sheets were camped next to homes with grand facades, and neighborhoods of teeming humanity gave way unexpectedly to lush, forested parks.

By nightfall, we were tired and famished. After taking tea in the Imperial’s Atrium, beneath a high dome and serenaded by the splash of an indoor fountain, we headed for Bukhara, a restaurant specializing in the cuisine of the Northwest Frontier, now the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

After a 90-minute wait, we were ushered into a beautiful room of stone walls and dark wooden beams. We perked up when we saw the plateloads of tandoor-cooked chicken and lamb heading for other tables, and decided to try both. The chicken, marinated with cream cheese, vinegar and coriander, was succulent, as was the lamb marinated in Indian spices. But we were nearly reduced to tears by Bukhara’s version of dal — rich, flavor-packed dark lentils that had been simmered overnight with garlic, ginger and tomatoes. We had the overwhelming sense that this was the kind of meal you couldn’t match in an Indian restaurant outside the subcontinent.

Early on Day 3, we headed for the second point on the Golden Triangle, making the five-hour drive southwest to Jaipur, a city ringed by rough-edged hills, topped with walls and forts. Its most striking feature is the old town center known as the Pink City, named for the color it was painted for a 19th century visit from Prince Albert.

We met up with Vikram, our Jaipur tour guide, who warned us about the hawkers who swarmed like bees around tourists. “There are many people selling things here,” he said. “If you show interest, I can’t help you.”

Our first stop was the City Palace, built in the early 18th century by Jaipur’s founder, Maharajah Sawai Jai Singh II. We strolled through the sprawling complex of chambers and pavilions, pausing in the courtyard outside the Moon Palace, home of the current maharajah, where we spotted a young boy playing in a passageway behind the velvet ropes. It turned out he had a reason to be there: He was the 12-year-old crown prince.

One of the challenges of a short trip, especially for shopping-challenged men like us, was finding time to pick up souvenirs for the folks we left at home. Stan’s wife had given him some advice: Watch what Rich does, because he always buys the nicest things for his wife.

Jaipur is known for its semiprecious stones, so we browsed for a long hour at Jewels Emporium, watching Steve try on bracelets and Rich try on necklaces. (“Yes, Rich, that looks lovely on you.”) Stan didn’t follow his wife’s advice; he later bought her a sari and a $2 T-shirt.

We hit the road early the next morning, and the 145-mile stretch of rough two-lane from Jaipur to Agra proved our driver, Prakash, to be a master of the Indian road. That left us free to concentrate on the passing scenery. We sped, and sometimes inched, through roadside communities of al fresco restaurants with plastic chairs, bicycle repair shops and tire stores. Like in a video game, we weaved in and out among goats, monkeys, camels, cows, elephants, carts, tractors, an army cannon and women in saris of stunningly rich colors placing patties of cow dung out to dry, to be burned later as fuel. We passed women pumping water, men urinating, children being bathed in standing water. Ancient forts dotted the hills above.

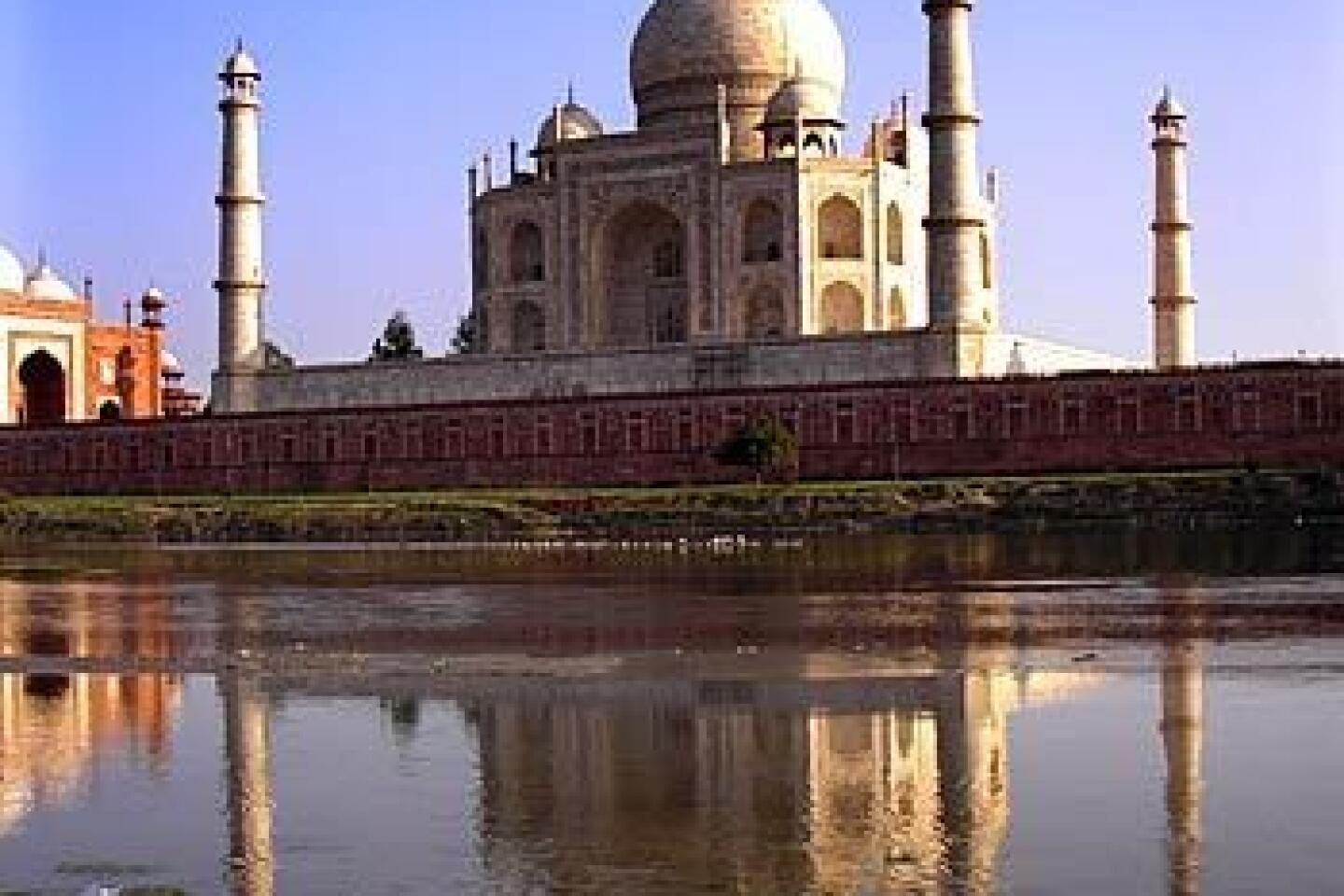

Entering Agra from the west, we headed for the Agra Fort, a vast fortified palace built by the Mogul emperor Akbar. It was at the fort’s drawbridge entrance that we caught our first glimpse of the Taj Mahal, shimmering in the distance on the banks of the Yamuna River.

We had heard that the view from across the river was spectacular in late afternoon, so we drove across a narrow bridge clogged with a wild assortment of rush-hour traffic — tiny, motorized three-wheel rickshaw taxis, men pulling carts of rice. Then we hiked half a mile to the river and stood mesmerized by the Taj and its reflection in the water.

We were joined by a barefoot boy and girl, who wanted us to take their photo in front of the mausoleum, in exchange for a tip. Although I was the only one to oblige, the boy was certain that Stan had secretly snapped his picture. Even when Stan showed him the digital frame, the boy wasn’t fully convinced. (The next day, as we were standing beneath the onion dome of the Taj, Stan impishly aimed his camera back across the river, saying, “I’m going to get a picture of that kid.”)

The marble Taj is an architectural masterpiece, perfectly symmetrical with four minarets and matching mosques on two sides. Because worshipers must face east, only one of the mosques is functional; the other was duplicated for symmetry. The minarets lean slightly but noticeably outward, a design feature meant to prevent them from damaging the central dome in case of earthquake.

Though the monument’s beauty is striking, the legend behind its creation is as captivating. Shah Jahan had the complex built, over 22 years by 20,000 workers, as a mausoleum for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died while giving birth to their 14th child and was entombed beneath the center of the dome. When Jahan died 35 years later, his son placed the tomb next to his wife’s, upsetting the Taj’s symmetry.

Not that it mattered, because from any angle the Taj Mahal is beautiful. Later, we checked into one of the most stunning hotels in the world, the 6-year-old Oberoi Amarvilas. At about $600 a night per room, it seemed outrageously expensive, but it was worth it: Every room opened onto a dead-on view of the Taj, less than half a mile away.

We gathered on one of the rooms’ balconies with a bottle of wine to celebrate our arrival. The hotel’s beautifully landscaped grounds gave way to a thick green forest sweeping to the front of the Taj. As the sun set amid a smoky haze, we felt an overpowering sense of accomplishment.

We toasted our shared desire to see the world and the satisfying journeys that had resulted. Rich told us how he had once assembled a list of things he wanted to see in his life. “I’ve now seen everything I wanted to see as a kid,” he said.

The view was so stirring that we all wished our wives and children could be with us. Steve said his wife would love it — but only if she could be magically transported from Los Angeles to this balcony and returned home the same way.

For us, though, the destination was worth the trek. We wouldn’t spend our lives wishing we had made the journey. In the end, the choice to go quickly or not at all was an easy one.

It wasn’t long before the conversation turned, naturally, to our next adventure. Rich suggested Lhasa, the storied 12,000-foot-high city in Tibet, a 48-hour train ride from Beijing.

In other words, we agreed, a very long weekend.

scott.kraft@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.