The best part of Joshua Tree may be what you never see. That’s a good thing.

- Share via

There’s a regenerative power in the desert, no matter how bone-chillingly cold it is on a January night.

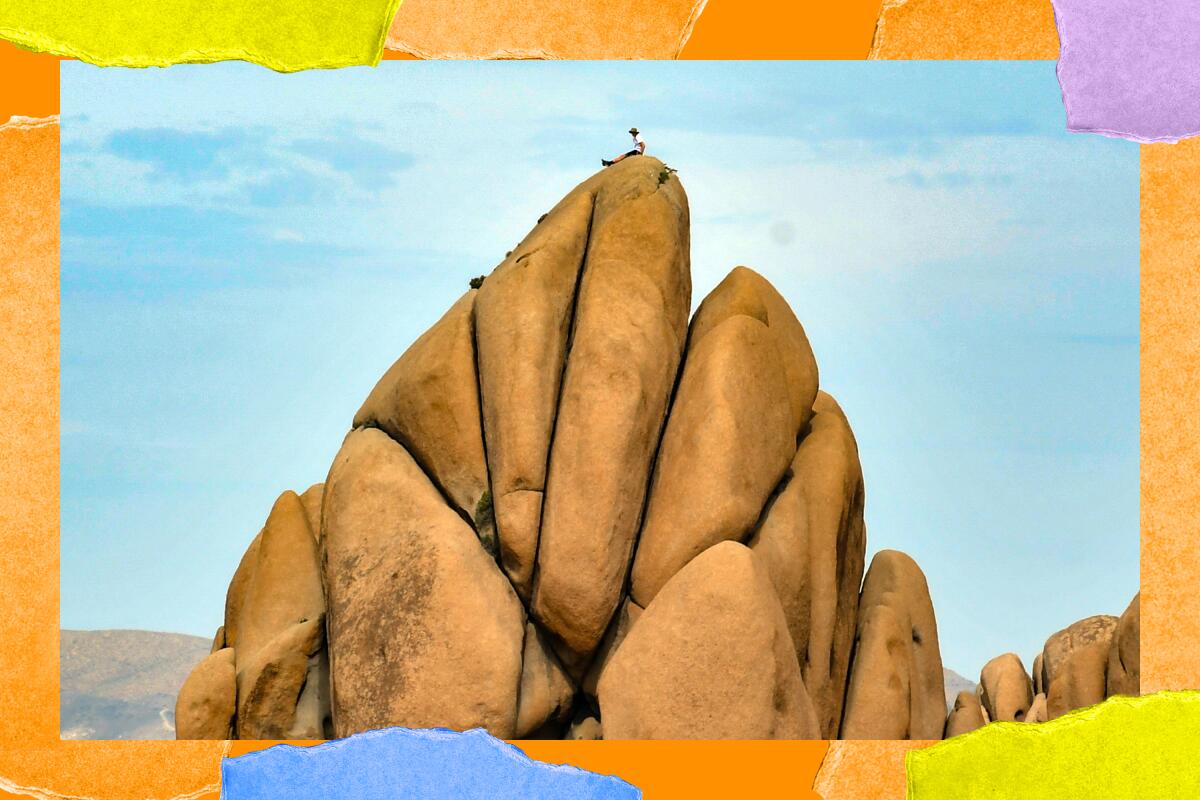

Last weekend, I saw plenty of gorgeous granite — and even climbed it. Jumbo Rocks Campground in Joshua Tree National Park is radiant with inselbergs, or islands of rock formed by erosion, that are millions of years old. The feeling of hiking in the shadows of these behemoths is transformative.

Our group of four included my son, who made the rock formations his personal playground, yelping like a coyote pup as he clambered up them in his Black Diamond full-body harness, his adorably tiny chalk bag strapped to his waist. I shivered in the frigid gusts of wind, but luckily we’d had a rain-free (and delightfully Internet-free) day.

I’d wanted to hike across the sand dunes I had heard about, including some of the 640 Cadiz Valley acres newly protected by the Mojave Desert Land Trust (MDLT). But, as we picked up s’mores ingredients at the Twentynine Palms grocery store, I briefly got online. What I read in the MDLT press release announcing the Mojave Trails National Monument area stopped me in my tracks. “As there is little human disturbance, this special property has ample signs of wildlife, with numerous animal tracks visible in the sandy soil,” the MDLT conservators wrote.

As explorers, we sometimes struggle to exercise restraint. We always want to see what’s over the next peak; we’re compelled to take our trek off-trail to forage a plant or to take a photo of a spectacular view. We were here, we recount to ourselves proudly, browsing our favorite memories on our phones.

But do we need to see the most remote areas? Wildlife is currently vibrant in the Cadiz Valley, but it might not always be (it certainly isn’t at the campgrounds by day, unless you count a few roadrunners zooming by, or a ground squirrel stealing campers’ food). All of these populated campground areas were once wild, and even the Joshua trees face risks.

Lightly treading explorers still bring our bright lights at night, our sound pollution, our movements, and unfortunately, our trash, which blows away with the wind, even when we fully intend to pack out. The area already faces environmental threats; last year, the Biden administration opposed a Cadiz groundwater pumping permit that could harm the water supply of local wildlife, including watering holes for bighorn sheep, frogs, birds and deer.

Dunes are particularly susceptible to our impact. They may look like outsized waves of sand, but they shelter flora and fauna, and hold water like huge sponges. In the Cadiz Dunes Wilderness, herbs like the Borrego milk vetch somehow thrive among the sandy hills. This herb is a charming sage green, bearing a pinkish-purple flower that bursts forward jubilantly in the spring, as if it doesn’t care that it’s surrounded by hundreds of acres of sandy soil.

Appearances can be deceiving, even when it comes to a superbloom. The Borrego milk vetch is actually a rare and endangered native plant that needs to plumb deep into the sand to find water. Milk vetches are glorious little sun-worshipers that cling to life in the harsh desert, and pollinators like bees and butterflies love them. Insects, in turn, provide sustenance to birds. I don’t need to tell the bird-watching readers of this newsletter about the life-giving seed dispersal and pollination performed by Mojave Desert birds, who are short on water and fighting for their lives.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t ever visit remote areas if we do it occasionally and with respect. Knowing our Earth helps us conserve it, and sometimes, that includes a visit. But knowing when not to visit a remote area is equally important, and that involves assessing environmental tolls, listening carefully to rangers and obeying park rules. I try to ask myself if I’m giving back as much to an area as I’m taking, and usually, the math says no. If you do go, here’s how to best preserve the remote areas you visit.

1. Be a prepper. Bring everything you need to survive: sun protection, food, a map and compass, a personal satellite communicator and more water than you think you need. This helps avoid taxing local rescue and emergency teams who have to come and save you if you end up in trouble.

2. Camp on durable surfaces. Instead of forging a new campsite in a wild, remote spot, use existing campsites or hard established surfaces.

3. Pack in and pack out. Keep remote areas as pristine as possible by taking with you everything you brought. Bring a designated trash container and a compost bag, too.

4. Give as much as you get. Help local conservation efforts like the MDLT, also known as the California Desert Land Conservancy, by making a small donation each time you visit.

5. Be a seed keeper. Volunteer at MDLT’s native plant nursery and seed bank, collecting seeds from endangered native plants and tending seedlings. If you can’t volunteer, you can become an official Friend of the Mojave Desert Seed Bank by donating.

When I think back on the weekend we spent in Joshua Tree, I’m happy just knowing that the Cadiz Dunes exist and that the animals there are able to live without much human interference. I don’t feel I have to be the first of my friends to go to such a remote area. Hopefully, we can all visit someday, when the area is thriving and global warming impacts on the flora and fauna have been mitigated or reduced.

3 things to do

1. Fantasize about the future of the final frontier. Bring your future astrophysicists and engineers to this LAist Studios live event at the Crawford Family Forum in Pasadena on Thursday from 7 to 8 p.m., where you’ll be regaled with out-of-this-world stories from M.G. Lord, host of a podcast about the storied genesis of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory itself, and Nagin Cox, JPL Systems Engineer. They’ll also talk about how STEM education is preparing young learners for the final frontier, and how NASA landed in Pasadena. While in-person seats for the event are now sold out, you can attend virtually and pay what you wish. For more information, go here.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

2. Learn about the giants towering above us. If you’ve ever wondered about the giant live oaks towering above your house or your local park, the Theodore Payne Foundation is offering a tree walk-and-talk on Saturday, Feb. 11, from 1 to 3 p.m. Absorb fascinating facts about our tall, oxygen-giving friends with arborist Alison Lancaster, who’ll share her ample knowledge of sycamores, Torrey pines, palo verde, Santa Cruz Island ironwood, and of course, our ever-present oaks. Tickets are $25 for members and $35 for non-members. Go here to buy them and for more information. The January walks are currently sold out, so reserve ahead!

3. Do a Malibu morning hike. One of those Angelenos who only hoofs it to Malibu in summer? Don’t turn your nose up at a winter morning hike through the Charmlee Wilderness Park chaparral to a breathtaking overlook of the park and the ocean. This hike, for ages 6 and up, starts on Saturday at 8:45 a.m. The hiking guide will give details about local native plants, like lupines, oaks, and sticky monkey flowers, and you’ll see birds and insects busy with their morning duties. Be aware that terrain can be uneven here and that there may be some uphill hiking. The event is free, but you’ll want to register as space is limited.

The must-read

We Angelenos are constantly on our feet, doing and seeing, but what happens when your mind says go and your body says no? As we screech into our 40s, some of my triathlete friends and hardcore hiker pals are finding it more mentally than physically challenging to pause and alter their expectations of self. Yes, you can do triathlons at age 72. But if you’re unable to slow your frenetic pace to heal from an injury, or even contemplate life off the “treadmill” of doing, how does that affect your body and mind?

In her advice column at Outside, Blair Braverman reassures a perfectionist athlete who’s struggling with a slow recovery from shoulder surgery for an old injury. The key phrase here to me is “old injury.” So many of us delay surgery for fear it will slow us down. Or we never properly treat an old injury, which pops back up like a Whac-A-Mole later in life. And a lot of us have been taught to work through pain. I didn’t want to stop when I got shin splints running for crew in high school, so my coach had to persuade me. I got hit by a car in my 20s and, because I’m stubborn as a mule, I got back on my bike that instant and biked home. Nor did I want to rest in a sling for six god-awful, boring weeks after fracturing my radial elbow joint roller-skating with my husband at Moonlight Rollerway. I hate resting so much I used to wish (before having a baby!) I didn’t have to sleep. Like the athlete who wrote to Braverman, I’m absolutely hungry to do it all.

Braverman asks the athlete to reframe what being a “tough woman” means to herself, reminding her that it also means “having the courage to make changes, and to take care of yourself, even when it’s really hard.” That “toughness can take the form of patience, or acceptance, or hope” — and it’s not on hold when we rest. In fact, those may be the toughest, and most important, moments of all.

Now, how about two days of silent meditation and 10 hours of sleep? Sound boring to you, too? It’s all about the baby steps.

Happy adventuring,

Check out “The Times” podcast for essential news and more.

These days, waking up to current events can be, well, daunting. If you’re seeking a more balanced news diet, “The Times” podcast is for you. Gustavo Arellano, along with a diverse set of reporters from the award-winning L.A. Times newsroom, delivers the most interesting stories from the Los Angeles Times every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

P.S.

Like so many of you, I’m grieving the victims of the mass shootings in Monterey Park and Half Moon Bay. I know it’s little consolation, but running or hiking helps take my mind away from the ever-present danger of the society we live in — even for just an hour or two. This Saturday, I’m heading out to Eaton Canyon for a trail run (properly covered-up in this cold, natch), with Nature Tails storytime after with my kiddo.

What are you up to this weekend and next week, with the chilly temps and impending rain? Share pics of yourself living large — or photos of yourself resting and recovering so you can hit the trails again soon.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.