Birdwatching includes bird-listening. How to connect with nature by recording birdsong

- Share via

If you were old enough to buy CDs in the ’90s, you may remember listening stations at superstores that featured music by some of nature’s noisiest creatures: birds. These CDs blended classical music like Brahms’ lullaby with the plaintive call of a loon, or smooth jazz coupled with the howls of wolves (“Jazz Wolf,” anyone? It was a 1993 classic). Sometimes the composers even threw in a frog ribbit or cricket chirp in this golden age of nature mashups. I would put on the headphones at the listening station and chuckle at the sound of a barn owl hooting to Beethoven’s Fifth, wondering who the target audience was.

If you prefer your nature sounds unadorned, consider recording them yourself. Maybe you’re thinking, “Why bother, when I can go to All About Birds and hear those sounds anytime?” The answer is as simple as you want it to be: Because you need something to keep you interested while hiking, because recording bird sounds captures memories, because you like audio journaling, because you want to contribute to research — or because birdsong can be as ephemeral as the bloom of a morning glory, and you want to hold onto it. If you’re inclined to set your bird sounds to smooth jazz later, that’s your prerogative.

Whether it’s the high-pitched squawk of a dramatically gray, black and white Clark’s nutcracker at Mammoth Lakes, or the fairy tale music of a Swainson’s thrush singing from your garden bird feeder, these sounds are as varied as human voices — and there’s a charm to studying them on your own.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientist Lance Benner, who captures radar imaging of asteroids in his day job, regularly records birds while hiking and mountain biking. Benner says he has been fascinated by bird vocalizations since he was a child, when he first learned the calls of birds such as northern cardinals, barred owls and common loons.

“Some bird songs are utterly magical,” Benner says. “I love listening to them and love preserving brief moments in time with recordings.”

Recording bird sounds is how Benner and many others learn them, tuning into what birds may be nearby without being able to see them. “I grew up in New England, where it can be hard to see forest birds in the spring and summer after the leaves come out. If you learn the songs, you can identify many, many more species than visually.”

As far as recording equipment, Benner is fond of both simple solutions like his iPhone and more complicated equipment. When using his iPhone, he turns to his Voice Memos app or Voice Record Pro; the latter can perform simple audio editing and conversion to different file formats. There are also bird-specific iPhone apps that record, including Song Sleuth and Bird Genie, which can identify up to around 200 species.

Is it really possible to get a decent recording from your phone? “It most certainly is,” Benner says. You can also extract sound files from the audio of a video, including on an SLR camera. Sounds haven’t been as good, Benner says, as from sound recorders, but these devices are “surprisingly capable.”

Benner imports the mp4 files from his iPhone into Audacity or Raven Lite, where he can more closely examine and edit them. For an Android phone recording, he recommends RecForge II. You can also plug an external microphone into your phone for better recordings.

If you’d like to increase the quality of your recordings and have a few hundred bucks to divert to your outdoor budget, you can use a separate recorder with an external microphone, which reduces background noise. Your best option for recording low-frequency sounds, like those from owls, mourning doves and grouse, is a shotgun microphone. These long, barrel-shaped microphones absorb sound from a specific direction. You can get them at any Best Buy or major electronics stores, as well as online from a variety of retailers, including B&H Photo Video and Sweetwater.

Benner typically uses a Sound Devices MixPre-3 recorder and an old Olympus LS-10 recorder that’s no longer available for purchase, with an 18-inch Sennheiser ME67 shotgun microphone (no longer available, but you can try a variety of other mics, including the 10-inch Sennheiser MKE 600 shotgun microphone) while hiking. A windscreen over the mic helps filter out wind.

When seeking to capture sensitive sounds coming from multiple directions, he has also used an omni directional Sennheiser ME62 with a Telinga Parabolic dish.

If you’re looking to record at night (owls and other nocturnal birds, particularly) or at other times when you won’t be near your equipment, consider an open acoustic device called a sound logger, like the AudioMoth or Song Meter Mini, which can automatically record at specified intervals for up to several weeks. Benner discreetly straps these sound loggers to trees far from the trail so they’re not vandalized, leaving them out for a couple days up to a month, and then transfers the files from the SD card to his hard drive to check them. They’re particularly useful, he says, in recording the early morning birdsong called the dawn chorus in the chaparral habitat, and mid- and high elevations in the San Gabriel mountains.

If your recordings are coming out fuzzy or you can’t quite hear the birds, Benner says to get closer and try to record in quieter areas. Don’t talk, don’t shuffle your feet and try not to record in rain, near rushing water or in windy conditions. You may be able to crouch behind a car or a building in order to block out some of the undesired sounds. Play back recordings to check them, and if birds aren’t audible, try recording again. It may be easier to obtain good recordings when you’re alone as opposed to when you’re in a group. Turn on the low-cut filter, which removes unwanted low-frequency sounds like the hum of a nearby engine or building HVAC system, and turn up the sensitivity and gain, which controls how loudly your birdsong is recorded.

Sharing your recordings is part of the fun — and a great way to contribute to both an international hobby and an important field of research. Benner says that important conservation changes have been made due to bird recordings, like the decision to restore bird habitat in the Devil’s Gate Dam restoration project after recordings of an endangered species, the least Bell’s vireo, were made at Hahamongna Watershed Park in Pasadena. Declining species, like spotted owls, may be hard to see, but recordings may help document the numbers of the species.

“There’s an acute need to obtain more sound recordings of many species, of the dawn chorus and sounds at night,” Benner says. He uses recordings of red crossbills to understand the populations of that species, a type of finch, that occur in Southern California and in the Sierra Nevada. “There are at least 12 populations of red crossbills in North America, and the best way to identify them, by far, is by sound,” Benner says. “In 2011 and 2012, we discovered that the red crossbills in this area are types 2 and 3. None of the others have been documented here yet.”

To share his findings with the world, Benner converts his avian audio files to mp3s and uploads them to two sites: eBird and Xeno-Canto. eBird files go into the Macaulay Library of sounds at Cornell University, where they exist like museum specimens in archival formats and are used by researchers for academic papers and conservation planning, including site and habitat management and informing law and policy. Xeno-Canto, a Dutch archive, is for everyone, including hobbyists; anyone can download files, and it’s easier to search for files than on eBird.

To learn more about how to record birds, watch Benner’s introductory talk for Los Angeles Birders, as well as his follow-up talk on advanced sound equipment for recording birds.

3 things to do

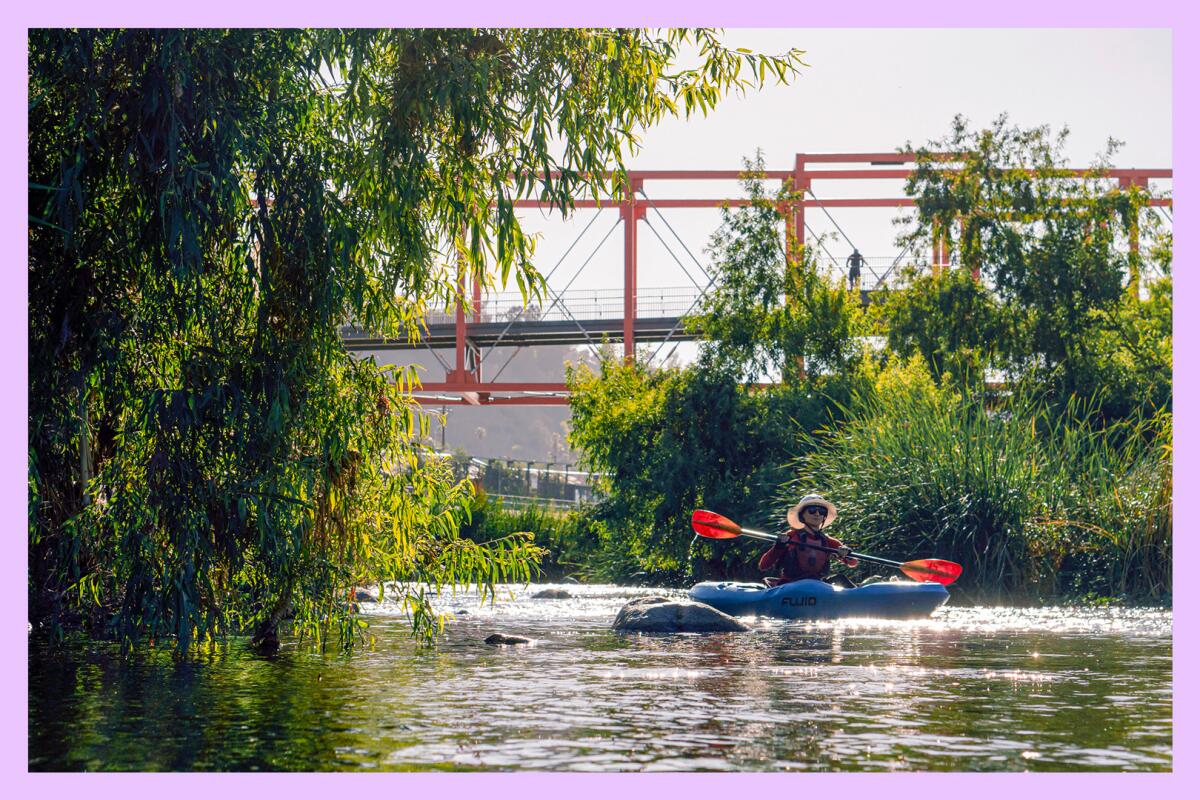

1. Tour the L.A. River by kayak. If you’d rather paddle Elysian Valley than bike its path, join nonprofit L.A. River Expeditions for an easy 1.5-mile kayak experience through the area’s Class I rapids from 11:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Sept. 2. Paddling experience is recommended. After a brief hike to the launch spot and a safety lesson, you’ll set off to see birds, plants and cityscapes. You’ll also face the challenge of navigating gentle rapids, rocks and sandbars. In shallow waters, you’ll go through the motions of standing up, walking, carrying your kayak, sitting down and paddling again. The kayaks provided have a weight limit of 215 pounds. Tickets cost $75, and are available here.

2. Hang with KCRW at its HQ. The NPR affiliate, which you can hear at 89.9 FM, is throwing a big party at its Santa Monica headquarters from 7 to 11 p.m. Saturday. It’ll feature the easy, breezy vibes of French band Pearl & The Oysters, plus KCRW DJs Francesca Harding and Anthony Valadez. Entry is free with RSVP, but KCRW members get priority entry at the door and access to the quicker member line at the bar, plus $1 off all drinks and discounted merchandise. There will be food trucks too, so come hungry. Find more info here.

3. See Earth’s minerals sparkle. Caught the rockhounding bug? Meet with fellow treasure hunters at Pasadena Lapidary Society’s 63rd Gem & Mineral Show, coming up at the Arcadia Masonic Center. You’ll be able to see and purchase gems, minerals, crystals, jewelry, geodes, fossils, slabs and rough rock and lapidary supplies. Plus, there’ll be demonstrations, exhibits, a raffle, a silent auction and grab bags and prizes for the kids. The show runs from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Aug. 26 and from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Aug. 27. Admission and parking are free.

The must-read

Speaking of those who collect rocks and minerals for fun, they’re facing a fresh challenge to their old hobby. Rockhounding was, according to Times staff writer Louis Sahagún, “pretty much born in Southern California in the 1930s, with the advent of Route 66, and it enabled people in their Model Ts to venture into the desert and explore dirt roads and look for rocks and minerals.” In rockhounding’s heyday in the 1950s, Sahagún notes that as many as 2 million homes had lapidary equipment, which was used to polish and cut rocks into curiosities like bolo ties, bookends and crystal balls.

Now, one of the hot spots for collecting in our area, Mojave Trails National Monument, where you’ll find agate, quartz and jasper, may soon be off-limits. When the U.S. Bureau of Land Management finalizes its management plan this year, it may choose to classify rock collecting as a form of mining, the latter which is regulated on public lands. But rockhounding is not mining, hobbyists and mineralogists insist. Lisbet Thoresen, a mineralogist, makes a good point: “How are students going to learn to be geologists if not in nature’s own classroom?”

Rockhounds are asking the BLM to make an exception for the Mojave Trails National Monument, which Sahagún calls the “Valhalla of rockhounding” in his interview with Lisa McRee of “L.A. Times Today” (the video is at the bottom of the article). The exception could then be used as a guide to allow rockhounding at other public sites. Sahagún says rockhounds make another good point about hunting at the national monument: “Why is it OK to shoot a deer in a monument and drag it home, and not take a piece of agate off the ground?’

For those who argue that rockhounding might deplete our natural supply of rocks and minerals, that’s unlikely, according to Sahagún. With the current BLM rules, you’re allowed to take up to 25 pounds of rocks, minerals and semiprecious gemstones per day, or 250 pounds per year, for personal use, but most rockhounders are searching for uniqueness, not heavy troves of rocks. If it’s for something other than personal use, such as landscaping or selling, collectors need a permit to do so on public land. Rockhounding is generally prohibited in all national parks.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

Are you heading out to see the Perseids this weekend? Check out Matt Pawlik’s guide on where to catch the best of this year’s showy showers. Aug. 12 and 13 are the best days for seeing up to 100 meteors per hour. You won’t want to miss this year’s display, which will be easier to see with a less full moon than last year.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.