From the Archives: The 1942 Battle of L.A.

- Share via

Following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, war jitters swept the Southland. By February 1942, air-raid sirens, searchlights and anti-aircraft guns filled Los Angeles. Blackouts and drills were common.

Then on Feb. 23, 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced and shelled oil installations at Ellwood, north of Santa Barbara.

In a Feb. 24, 1992, Los Angeles Times article, Jack Smith reported what happened next:

It was on the night of Feb. 25, 1942, that Los Angeles experienced the Great Los Angeles Air Raid. It was a night when everyone’s fears apparently were realized — Japan had brought the war to mainland America, and Los Angeles was the target.…

The Great Air Raid began at 2:25 a.m. on that clear moonlit night when the U.S. Army announced the approach of hostile aircraft, and the city’s air raid warning system went into action for the first time in the war.

Suddenly, the night was torn by sirens. Searchlights swept the sky. Gun crews at army posts along the coastline began pumping ack-ack into the moonlight. (In the entire episode, 1,433 rounds would be fired.) …

Thousands of volunteer air-raid wardens tumbled from their beds and grabbed their boots and helmets--those who had helmets — and rushed into the night. Tens of thousands of citizens, awakened by the screech of sirens and the popping of shells, jumped out of bed and, heedless of blackout regulations, began snapping on lights. It was pandemonium. …

Although no bombs were dropped, the city did not escape its baptism of fire without casualties, including five fatalities. Three residents were killed in automobile accidents as cars dashed wildly about in the blackout. Two others died of heart attacks.

Several persons were injured hurrying to their various posts. A radio announcer ran into an awning and suffered a gash over one eye. A police officer kicked in the window of a lighted Hollywood store and cut his right leg.

The toll among air-raid wardens was especially high. (They were said to have acted with valor throughout.) One fell from a wall while looking into a lighted apartment and broke a leg. Another jumped a 3-foot fence to reach a lighted house and sprained an ankle. Another fell down his own front stairs and broke an arm.

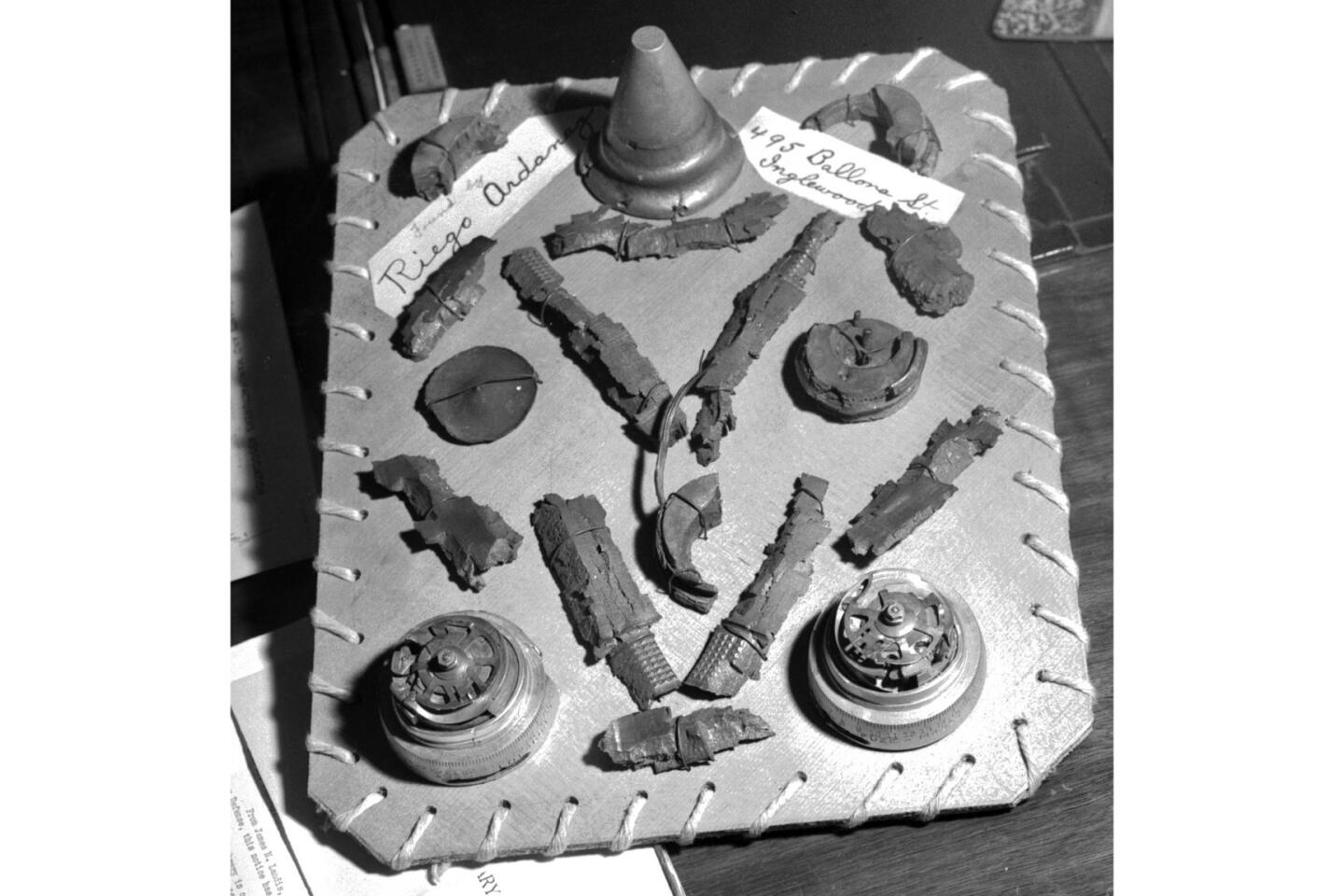

There was scattered structural damage caused by antiaircraft shells that failed to explode in air but did so when they struck the ground, demolishing a garage here, a patio there, and blowing out a tire on a parked automobile.

Exultation was in the air. The city had met its first taste of war with valor. It was exhilarating. But exultation turned to embarrassment the next day when the Secretary of the Navy said there had been no air raid. No enemy planes. It was just a case of jitters.

Embarrassment turned to outrage. The army was accused of shooting up an empty sky. The sheriff was particularly embarrassed. He had valiantly helped the FBI round up several Japanese nurserymen and gardeners who were supposedly caught in the act of signaling the enemy aviators.

The Secretary of War tried to save face by saying that while there were no enemy aircraft in the air, it was believed that 15 commercial planes flown by “enemy agents” had crossed the city. Though no one believed this gross canard, most agreed with the secretary that “it is better to be too alert than not alert enough.”

At war’s end, an Army document explained what had happened: (1) numerous weather balloons had been released over the area that night. They carried lights for tracking purposes, and these “lighted balloons” were mistaken for enemy aircraft; (2) shell bursts illuminated by searchlights were mistaken by ground crews for enemy aircraft.

The Japanese, after the war, declared that they had flown no airplanes over Los Angeles on that date. All the same, it was a glorious night, and I commend its memory to those who think Los Angeles has no history.

Jack Smith’s full 1992 article Stunning Acts of Bravery That Will Live On in Infamy is online.

On Feb. 26, 1942, the Los Angeles Times published a photo page that included a retouched version of the above searchlight photo and seven other images. The retouched version is the iconic image seen worldwide.

Back in 2011, I viewed the two negatives. The non-retouched negative is very flat, the focus is soft and it looks underexposed. Although I could not tell if the negative was the original or a copy negative made from a print, it definitely showed the original scene before a print was retouched.

The second negative is a copy negative from a retouched print. Certain details, such as the white spots around the searchlights’ convergence, are exactly the same in both negatives. In the retouched version, many light beams were lightened and widened with white paint, while other beams were eliminated.

In the 1940s, it was common for newspapers to use artists to retouch images because of poor reproduction. The retouching was needed to reproduce this image. But I wish the retouching had been more faithful to the original.

The Los Angeles Times published another retouched version of the image on Oct. 29, 1945. The white spots near the convergence of the searchlights are larger than in the 1942 version. This print is in the Los Angeles Times’ library and in poor condition.

Additional images are in the March 9, 1942, Life magazine. On page 22 is another photograph of searchlights from the night of the Battle of L.A. On page 19 is a story on the Japanese submarine attack on Feb. 23, 1942. On page 24 is a story on the removal of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast.

In addition, the Los Angeles Examiner archive at the University of Southern California has a couple of additional searchlight photos taken on Feb. 25, 1942.

This post originally was published March 10, 2011, with an update on Feb. 25, 2012.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.