In a time of pandemic, another rural hospital shuts its doors

- Share via

WILLIAMSON, W.Va. — The red “Emergency” sign glowed above the empty ER waiting room as Loretta Simon walked to the front door and posted a notice that Williamson Memorial Hospital was shutting down.

It was just after 1:15 a.m. The emergency room beds were vacant. The last staff on duty were clocking out. Soon she would switch off the heart monitor in the nurses’ station and watch its screen fade to black.

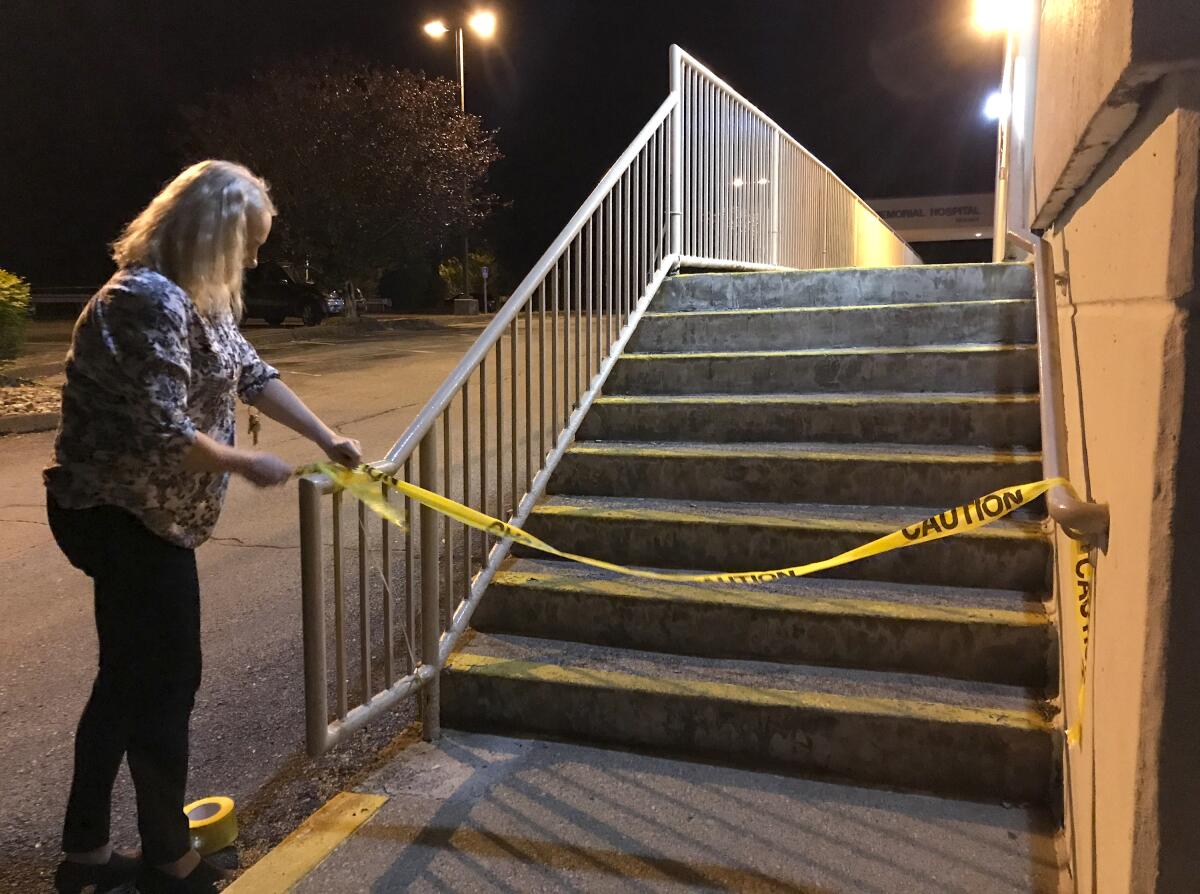

As the 48-year-old chief nursing officer stepped outside to block the ER entrance with yellow caution tape, she thought of all the people she had treated in her 25 years at the hospital: elderly patients who had suffered strokes, coal miners injured underground or laboring to breathe with black lung disease, patients of all ages who had overdosed on opioids and methamphetamines.

She wasn’t sure when, or even if, the emergency room would open again.

While big hospitals in places such as New York City, Detroit and New Orleans have been overwhelmed with a massive surge of COVID-19 cases, Williamson Memorial is one of hundreds of rural hospitals across the nation that have suffered from an altogether different crisis: a massive drop in patients.

The struggling 76-bed hospital in this rugged Appalachian coal country town of 2,800 residents was forced to close down last month after the global coronavirus pandemic hit just as administrators were trying to climb out of bankruptcy and work out a deal for another hospital to take over.

The only hospital in Mingo County, a remote pocket of West Virginia, Williamson Memorial did not treat any patients with COVID-19 — so far, the county of 23,400 residents has confirmed just three cases and one death. But the hospital’s net revenue was slashed in half as administrators halted nonessential procedures and visits to the emergency room plummeted from about 800 to 300 a month.

And so this former mining town, nestled in a narrow valley surrounded by hills of poplar and oak, has lost the hospital that served its people for more than a century.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Simon said. “It’s hard not to feel a little defeated that we have all these people in our hospital who have all this skill, who know how to take care of patients. But yet when the need is going to hit, we’re not going to be here.”

It’s a pattern that is likely to play out across the nation as COVID-19 unsettles the precarious finances of hundreds of small rural hospitals. Already, more than 170 have closed in the last 15 years, according to the University of North Carolina’s Rural Health Research Program. Last year, 18 shut their doors — the most since 2000 — and 12 have shuttered in the first four months of this year.

“It’s hard to envision a scenario in which we do not see a lot more hospitals closing,” said Alan Morgan, chief executive of the National Rural Health Assn., noting that in February, the nonprofit group identified more than 400 hospitals at risk for closure. “Things have only gotten significantly worse.”

According to a recent report by the American Hospital Assn., hospitals and health systems across the nation face unprecedented financial challenges in the coming months, with an estimated loss of more than $200 billion from COVID-19 expenses from March to June.

After cancelling all outpatient and elective procedures, which account for 70% to 80% of revenue, Morgan said, many hospitals are furloughing and laying off staff. In April, the healthcare sector lost 1.4 million jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, with nearly 135,000 hospital workers laid off across the country.

::

For many Williamson residents, the closure of their hometown hospital raises the unwanted prospect of traveling two miles across the Tug Fork River to the 148-bed Tug Valley ARH Regional Medical Center in Kentucky. Some West Virginians are wary of making that trip; they say their insurance companies do not cover out-of-state visits and they worry they might incur higher bills. Also, they point out, they cannot easily get to the hospital when the river floods.

Five years ago, the West Virginia Health Care Authority blocked ARH from purchasing Williamson Memorial, arguing that transferring services to a Kentucky facility could cause Mingo County residents “serious problems” in obtaining care.

The nearest in-state hospital is a 35-minute drive away.

Some residents here hope that Williamson Memorial, after going through a succession for-profit owners, can be resurrected.

Already, a local physician and entrepreneur, Dr. Donovan “Dino” Beckett, who trained at the Williamson hospital as a medical student and worked for the hospital for more than 15 years, has swooped in to purchase the hospital’s assets.

But Beckett, the owner of a federally qualified health and wellness center, is not sure he will be able to reopen the facility as a full-service hospital with an emergency room. His plans rest on how soon the U.S. can curb the spread of the virus.

“It just depends on how quickly the United States gets back to normalcy,” he said. “That’s what creates a little anxiety for me.… The uncertainty of what’s going on in the world right now creates a lot of angst that maybe it’s too difficult to pull off.”

The closure of Williamson Memorial has left many in this shrinking town wondering about its future. Just last month, Norfolk Southern eliminated 35 jobs at the city’s rail yard, built in 1901 to service the region’s coal mines.

“I’ve always said if you lose your community hospital, tumbleweeds are next,” said Mayor Charles Hatfield, who served as the hospital CEO until it declared bankruptcy.

With 100 full-time staff, the hospital served as an economic engine for the city. It was the main employer, Hatfield said, contributing more than $100,000 a year in property taxes and about a third of the city’s business and occupation tax revenue.

“The railroads left the area, the mines are shutting down,” said Cathy Hardin, a 66-year-old pharmacy technician at Hurley Drug Co., as she strolled down the city’s deserted main street wearing a face mask and blue latex gloves. “It’s just something else to feel sad about. Our town has no future.”

Closing the hospital not only puts stress on local restaurants and stores, but also makes it harder for Williamson to attract tourism and diversify its economy.

“What you are doing is setting up the future of a county to die, because companies don’t come to places where you don’t have a healthy workforce and a good medical infrastructure,” said Debrin Jenkins, executive director of the West Virginia Rural Health Assn. “It sets up this kind of Mobius loop of people getting sicker, young people moving away, and older people staying here that are sicker and poor.”

Like many rural hospitals facing financial collapse, Williamson Memorial’s problems began long before COVID-19.

Perched high up on a wooded hill overlooking this proud town that touts itself as “the heart of the billion-dollar coalfields,” Williamson Memorial has struggled in recent decades as the coal industry has become more mechanized and faced stiffer competition from natural gas and renewable energies.

In its peak in the 1930s, Williamson was a bustling hub of 9,400 residents with a thriving downtown that boasted a grand five-story Neoclassical-style hotel, theater and department store. While the hotel is still there, some stores are boarded up and many have been replaced by lawyers’ offices and pawn shops.

As well-paying jobs dried up and the town’s population dwindled, the hospital found itself treating a higher ratio of patients without health insurance or relying on government programs, such as Medicaid or Medicare, that do not fully reimburse treatment costs.

Working at the hospital, Loretta Simon witnessed the shifts in the community firsthand.

A decade after joining the hospital as a nurse in the childbirth unit, she had to switch to case management in the mid 2000s as fewer babies were born and the hospital shut down its obstetrics department.

Then the opioid crisis came. Between 2006 and 2016, two downtown pharmacies in Williamson dispensed more than 20 million opioid pills, thrusting the city into newfound fame as the opioid capital of America. Overdoses became a weekly, sometimes daily, routine in the ER.

A year after taking over the hospital in 2018, Williamson-based Mingo Health Partners filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, attributing its financial struggles to low reimbursement rates and “general difficulties of delivering healthcare in Mingo County.”

According to Gene Preston, who took over as CEO in October, the company worked over the last six months to overhaul a flawed billing system, streamline by cutting services like cardiology and oncology, and obtain interim financing to carry the hospital through early summer, when another hospital system could take over. But the coronavirus derailed his plans — not just by causing revenue to plummet, but by burdening other health systems that were interested in acquiring or partnering with the hospital and forcing them to postpone any agreement.

“We had no choice,” Preston said of the closure.

::

While West Virginia was the last state in the nation to report a confirmed case of COVID-19 and is now, after more than 1,400 cases and over 60 deaths, seeing a decline in cases, it is particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.

Mingo County, in particular, has an older, poorer and sicker population than that of most counties in the state, with high rates of heart disease, obesity, hypertension and diabetes. Many former coal miners have chronic lung disease.

“Any one of these risk factors would be a problem, but when a closure hits these rural communities that have a disproportionate share of multiple chronic health issues, it’s just horrific,” Morgan said. “It’s a tinderbox.”

In Williamson, Karen Reynolds, 65, a retired Mingo County teacher who lives a stone’s throw from the facility, said it was discomforting to look out at night and see darkness where it stands. Suffering from limited lung capacity as well as diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis, she feared traveling to a bigger hospital.

“It’s scary to think something like that is happening and we can’t go up the hill to the hospital,” Reynolds said. “We trust the people on the hill.”

Her husband, Jeffrey, 55, a former principal of Williamson High School, said he worried the facility would not reopen as a full-service hospital.

“It’s one thing to lose a grocery store. It’s one thing to lose a car dealership,” he said. “But when you’ve lost a hospital, you don’t just lose jobs and economic capacity. You lose the capacity to care for your citizens. That’s a big deal for us.”

Already, the closure of a hospital on the other end of the state has faced strong criticism from locals who say it is putting residents at risk.

Two weeks after Fairmont Regional Medical Center in northwest West Virginia closed in March, emergency responders decided to try to revive a 54-year-old Fairmont man with COVID-19 symptoms after he went into cardiac arrest rather than transport him to the nearest hospital half an hour away. The man died.

“I wonder if the hospital was open, could the outcome have been different?” said Michael Angelucci, who leads the Marion County Rescue Squad and is a Democratic member of West Virginia’s House of Delegates. “Could we have given this man a saving chance?”

Angelucci has urged West Virginia’s Republican governor, Jim Justice, to issue an executive order requiring Alecto Healthcare, the California-based for-profit chain that owns the hospital, to keep the facility open.

“We have a 100-bedroom hospital that is sitting empty while we have patients getting sick,” Angelucci said. “Not having a hospital in a time of a pandemic is unthinkable.”

For many Williamson Memorial workers, the medical threats posed by the virus feel less real than their new reality of unemployment.

As scores of nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists and physicians assistants filed into the ER to say goodbye before it closed, few wore protective masks. Many wiped away tears as they huddled in the nurses station — ignoring a sign urging them to stay six feet apart — to receive a ceremonial last call from the emergency dispatcher.

After leaning in to hug a nurse, Loretta Simon giggled.

“I’m not really practicing social distancing,” she said.

Waiting for her last shift to end in a hospital without patients, Jessica Browning, a 29-year-old physicians assistant, said she had no clue how long she would be able to keep up with her monthly $1,100 mortgage and $1,200 car payments.

Her next-door neighbor had already been laid off from the nearby hospital in Kentucky, so there was no chance of working for it. The hospital 35 minutes away was not hiring.

While Browning had heard of temporary assignments helping COVID-19 patients in Louisiana, she said, the assignments lasted 21 days, followed by a two-week quarantine, and she couldn’t imagine spending that much time away from her 3-year-old, Maeleigh.

“I think this really shows the problem with hospitals in general,” Browning said. “That we’re in a pandemic and so many healthcare professionals are being laid off.”

Simon nodded.

Waiting for coronavirus cases to spread, while closing down the hospital, just felt wrong.

“It almost feels like the barrier is just the financial situation,” Simon said. “We’re what I would call a rich country, compared to most, and our healthcare should be a priority.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.