‘It means everything’: Residents fear loss of community post offices to the coronavirus

- Share via

PHILADELPHIA — For some of the 2,000 or so year-round residents of Deer Isle, Maine, the fraying American flag outside the post office this spring was a reminder of the nation’s mood.

The flag was in tatters. It twisted in the wind from a single hook. But it was stuck in the up position, so the postmistress hadn’t been able to replace it.

“I was thinking what a metaphor it is for our country right now,” community health director René Colson Hudson said. “It was really important that the flag be replaced, as a symbol of hope.”

Colson Hudson, a former New Jersey pastor who moved to coastal Maine a few years ago, posted an online plea April 23 that sparked a community thread. Should someone scale the flagpole? Could the local tree-trimmer help? Did they need a bucket truck?

By week’s end, a secret helper had gotten the flag down. Postmistress Stephanie Black soon had the new one flying high.

Colson Hudson, 54, had rarely visited her post office when she lived in suburban New Jersey. But in Deer Isle, people exchange small talk in the lobby, announce school events on the bulletin board and pick up medications and mail-in ballots — while postal workers keep an eye on everyone’s well-being.

“Here,” she said, “it is the center of community.”

The financially imperiled post office, under attack by President Trump, has become a potent symbol for a Democratic Party looking for unifying causes.

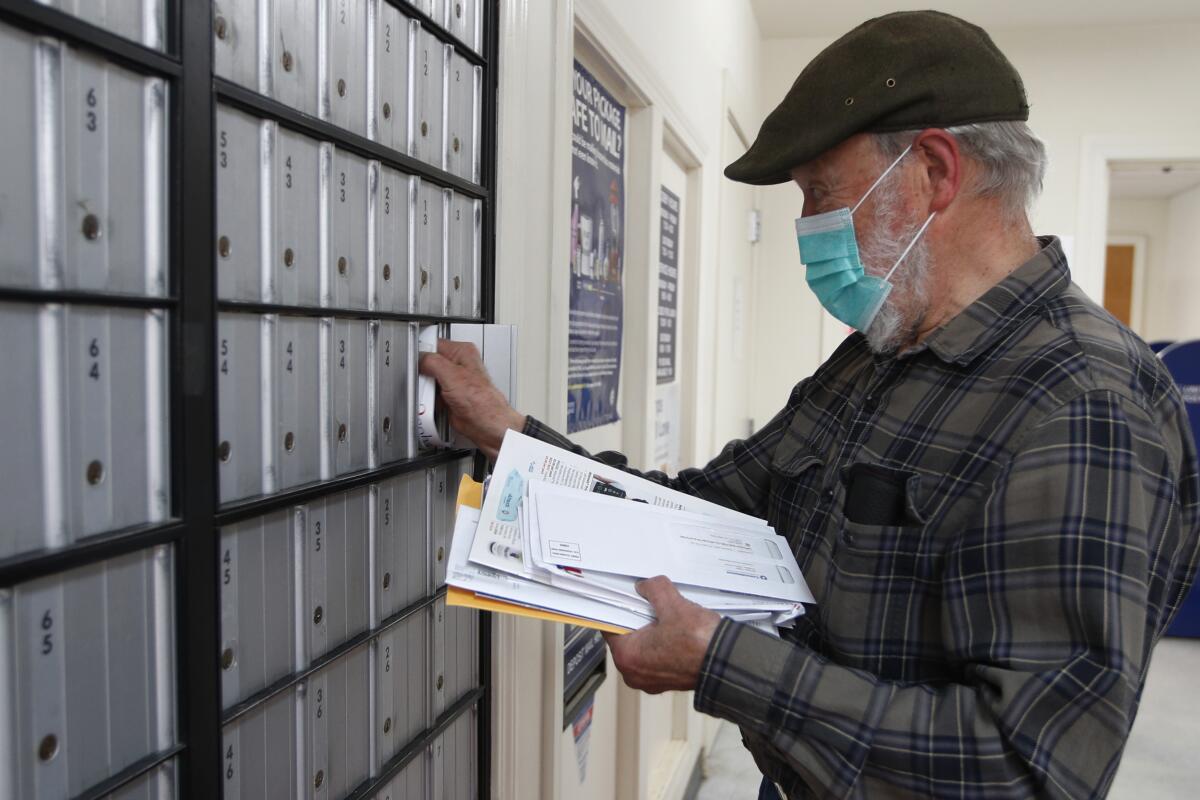

Many of the nation’s 630,000 postal employees are facing new risks during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they sort mail or make daily rounds to reach people in far-flung locales. More than 2,000 of them have tested positive for the virus, and a union spokesman says 61 workers have died.

For most Americans, mail deliveries to homes or post boxes are their only routine contact with the federal government. It’s a service they seem to appreciate: The agency consistently earns “favorability” marks that top 90%.

Yet it’s not popular with one influential American: President Trump, who has threatened to block the U.S. Postal Service from coronavirus relief funding unless it quadruples the package rates it charges large customers like Amazon, owned by Jeff Bezos. Bezos also owns the Washington Post, whose coverage rankles Trump.

“He is willing to sacrifice the U.S. Postal Service and its 630,000 employees because of petty vindictiveness and personal retaliation against Jeff Bezos,” Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) said last week. “That would be a tragic outcome.”

Postal Service officials, bracing for steep losses due to the coronavirus outbreak, warn that they’ll run out of money by September without help. They reported a $4.5-billion loss for the quarter ending March 31 — on $17.8 billion in revenue — before the full effects of stay-at-home orders sank in.

Some in Congress want to set aside $25 billion from the nearly $3-trillion relief program to keep the mail flowing. But with Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin pushing Trump’s priorities, the Postal Service has so far landed just a $10-billion loan.

“The Postal Service is a joke,” Trump told reporters in the Oval Office on April 24. “They’re handing out packages for Amazon and other internet companies and every time they bring a package, they lose money on it.”

The United States Postal Service is facing nearly $150,000 in fines after the heat-related death of a Woodland Hills mail carrier last summer.

Historically, the Postal Service has operated without public funds, ever since a crushing 2006 law required it to pre-fund 75 years of retiree benefits. It’s been around longer than the nation itself, with a rich history that includes Benjamin Franklin‘s tenure as the first postmaster general.

This month, the USPS Board of Directors appointed Republican fundraiser Louis DeJoy to the post. He succeeds Megan Brennan, a career postal worker who is retiring.

The president insists higher package rates could ease the Postal Service’s financial troubles. But most financial analysts disagree. They say customers would turn to UPS or FedEx.

Packages typically account for 5% of the Postal Service’s volume but 30% of its revenue. And package revenue has actually gone up during the coronavirus restrictions. Still, it hasn’t been enough to restore profitability, battered during the internet age by the decline of first-class mail.

Mark Dimondstein, president of the American Postal Workers Union, with 200,000 members, fears the Trump administration wants to destabilize the agency and then sell it off.

With more than 35 million Americans suddenly out of work, he wonders why anyone would put “600,000 good, living-wage jobs” at risk. Those Postal Service jobs have moved generations of Americans, especially African Americans and other minorities, firmly into the middle class.

Yet Trump, Dimondstein said, wants to privatize the operation when “here you have the post office serving the people of this country in maybe a deeper way than we ever have.”

On Henrietta Dixon’s mail route in North Philadelphia, every house has a story. Dixon seems to know them all.

Alvin Fields moved back to his block of two-story row homes after 40 years of working for Verizon. Jason Saal, 40, lives in an abandoned factory he bought for an art studio, but now hopes to make industrial-grade masks there.

Sharae Cunningham is also making masks, but the hand-sewn kind, some with African prints she sells for $6.

All said they would miss the Postal Service if it collapsed.

“It’s nice to have mail delivered by a letter carrier,” said Saal, who mailed out two boxes of masks through Dixon one recent morning and gave her several free ones. “It’s the person that you see, a government worker, every day, Monday to Sunday.”

They agreed that the neighborhood, one of Philadelphia’s poorest, would benefit from the kind of expanded services — such as low-fee check cashing and Wi-Fi — that’s the norm in European post offices and might help U.S. ones to survive.

“That’d be a great service. A lot of people need to cash checks,” said Cunningham, 40, who helps care for chronically ill parents, four children and a grandchild.

A few miles south of Deer Isle, Postmistress Donna DeWitt walks down to a boat dock each morning to retrieve her plastic bins from the 7 a.m. mail boat and carts them up to the tiny Isle au Haut Post Office a few hundred feet away.

With no bridge to the mainland and Wi-Fi and cellphone service on the island spotty, mail service is essential to the 70 or so year-round residents, who mostly work in the fishing and lobster trades.

“I don’t think you’d find most of the old-timers, for instance, paying their bills online. They depend on the mail for all of their business transactions,” said George Cole, the volunteer president of Isle au Haut Boat Services, a nonprofit that brings the mail over on the 45-minute trip from Stonington.

In rural Fayette County, W.Va., Susan Williams fondly recalls postmistresses who left homemade pumpkin roll out for customers, posted a note in the lobby when someone died and kept her mail-order geraniums alive.

Williamson Memorial Hospital did not treat any COVID-19 patients, but the coronavirus wreaked a devastating financial blow, causing ER visits to plummet.

“If I thought these plants were going to arrive while we were away, she would just open the boxes and water them for us,” said Williams, a retired journalist and teacher who lives in Falls View, about 35 miles east of Charleston.

With no home delivery there, she treks two miles to Charlton Heights to get her mail, trying to arrive after it gets put up at 10:30 a.m. and before the post office closes at noon. On a recent day in late April, her box held her mail-in ballot for the presidential primary. She planned to return it the next day.

“It means everything,” Williams said of the Postal Service.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.