Astroworld organizers had extensive medical, security plans. Did they follow them?

- Share via

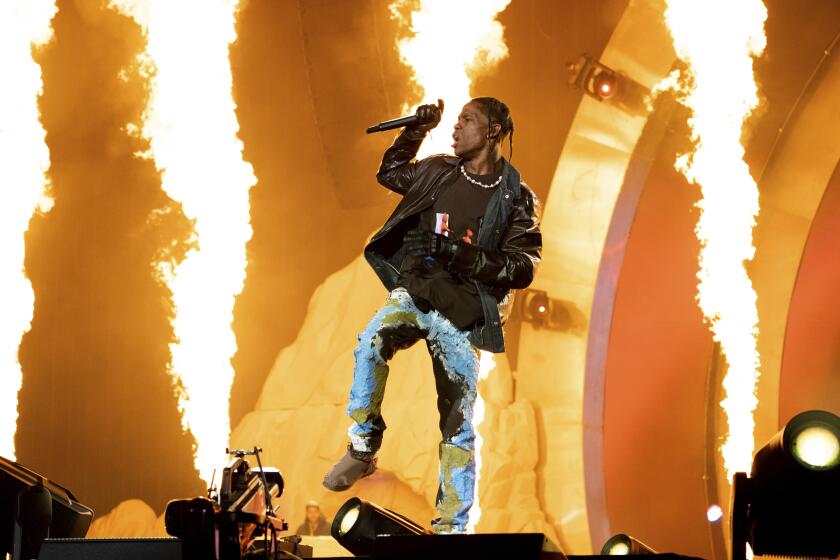

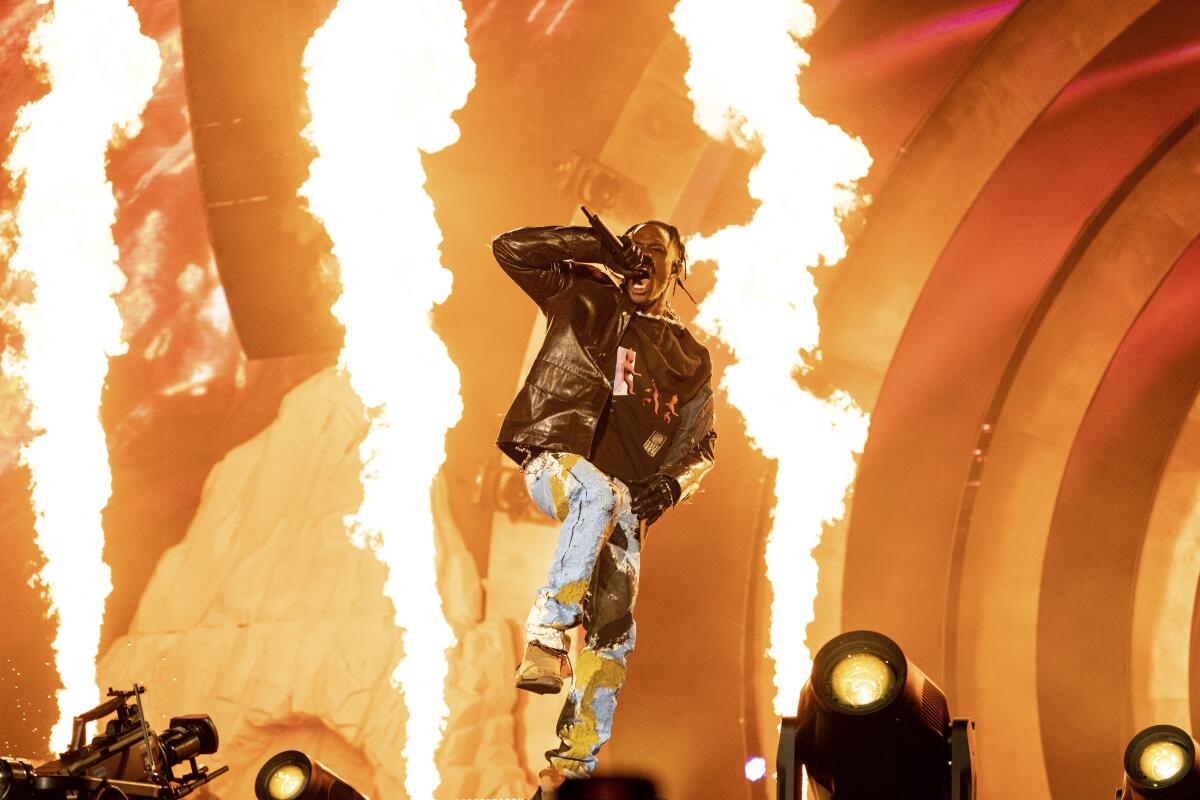

HOUSTON — A half-hour after rapper Travis Scott took the stage at 9 p.m. Friday, someone in the media pit called out for medical aid. In that instant, the Astroworld concert turned dangerous and surreal for Max Morbidelli, a 24-year-old former firefighter who was in the crowd with his sister.

“I jumped the barricade and found a girl who was passed out, supine and very clearly cyanotic, or blue,” said Morbidelli, an Advanced Emergency Medical Technician and graduate student at Auburn University in Alabama. The woman wasn’t breathing, didn’t have a pulse and no medical staff were visible, Morbidelli said. He started CPR.

“The scene was unimaginably chaotic,” he said. “The music was so loud. There were lights flashing. There’s people tapping me on the shoulder asking me questions. It was overwhelming.”

Morbidelli was caught up in unfolding chaos that had actually begun hours earlier when fans breached a barricade at the festival. Police intervened to bring things under control, but when crowds surged again that night, injuries mounted so quickly that medical staff were overwhelmed. Some concertgoers passed out. Others were trampled. A few climbed fences and begged Scott to stop the show, to no avail. By the time he left the stage after 10 p.m., bodies were being carried out on stretchers.

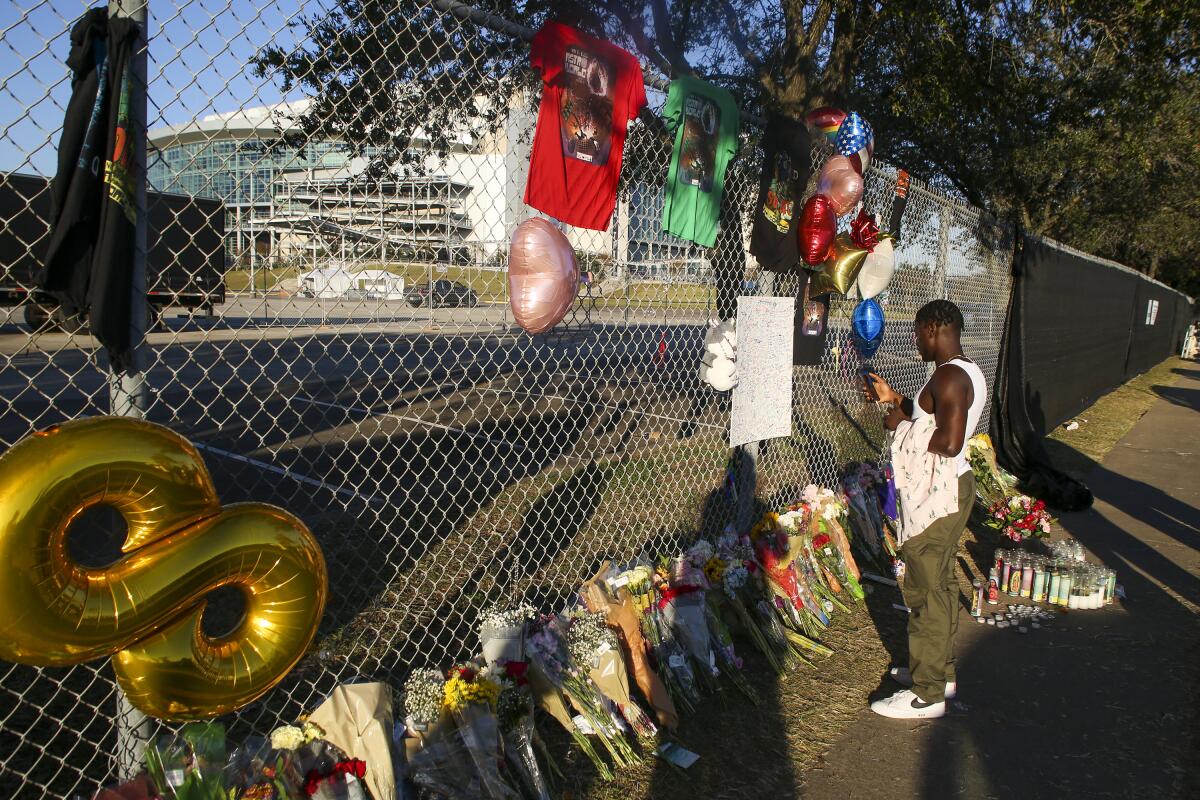

Eight people died, ranging in age from 14 to 27. Two dozen were hospitalized and scores more were injured. On Monday, the Houston medical examiner released the victims’ names, but their autopsies were still pending as local police and fire officials investigate what caused the night to turn deadly. At least one security guard was treated with naloxone for opioid overdose after reporting being pricked in the neck with a needle, Police Chief Troy Finner said, leading police to launch both homicide and narcotics investigations.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed against Scott and Astroworld organizers by those injured in the melee as questions have arisen over why the crowd surged and why it wasn’t contained during a day of unruliness. Some authorities also questioned why Scott continued to perform even as people fell unconscious and at least one ambulance appeared in front of the stage.

Before the concert, organizers had presented Houston police and first responders with two lengthy plans: A medical plan by New York City-based ParaDocs Worldwide Inc., and a security plan by Austin-based promoter ScoreMore Shows addressing potential emergencies.

“Based on the site’s layout and numerous past experiences, the potential for multiple alcohol/drug related incidents, possible evacuation needs, and the ever-present threat of a mass casualty situation are identified as key concerns,” the security plan said.

“The key in properly dealing with this type of scenario is proper management of the crowd from the minute the doors open,” the report stated. “Crowd management techniques will be employed to identify potentially dangerous crowd behavior in its early stages in an effort to prevent a civil disturbance/riot.”

Concert safety consultant Paul Wertheimer has been studying such tragedies since 1979, when he was an on-site investigator the night 11 people were trampled to death at a Cincinnati concert by the Who.

“What caught my attention,” Wertheimer said of the Astroworld plans, “is there’s no mention of crowd management of the audience in front of the stage. It’s not even addressed. Neither is moshing, crowd surfing or stage diving. Neither do the terms ‘crowd crush,’ ‘crowd surge,’ ‘crowd collapse’ or ‘panic’ appear anywhere.”

The medical plan estimated 70,000 would attend the concert, which was permitted for 50,000, according to Houston Fire Chief Samuel Peña. He said the outdoor space at NRG Park where the festival was held adjacent to an arena could have held 200,000, but that the event was permitted using a “more conservative” capacity formula, as if it was being held indoors.

“In that venue, it’s a gray area,” he said of capacity limits. “That’s something that needs to be addressed.”

Peña said it’s not clear how many people attended the concert. He requested a manifest of how many Astroworld tickets were sold, including 34,000 that were scanned, plus VIP and comp tickets. But others were caught climbing the fences to gain illicit entry during the day, he said. He had stationed about a dozen fire staff on site in case of an emergency, but it was Astroworld’s responsibility to protect those in attendance.

“It’s not what we do, to go to these events and set up a first aid station,” Peña said.

ScoreMore and concert organizer Live Nation did not respond to requests for comment Monday. They released a statement saying they had provided video footage to investigators and were cooperating, “to get everyone the answers they are looking for.”

Family and friends gather to mourn the first of eight music fans who died in a crowd surge at hip-hop star Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival in Houston.

ParaDocs Worldwide Inc. released a statement disputing allegations it lacked medical staff and equipment. It said it has been “providing medical care for large venue events” for more than seven years, that their emergency medical staff have a dozen years experience on average and have successfully treated more than 300,000 people.

“We were prepared for the size of the venue and the expected audience with a trained team of medics,” the statement said. “There were ample resources of medication, remedies, treatments and supplies, and the demand and usage did not exceed the onsite stock. From the beginning, the event occurred with a standard course of care throughout the day. The multiple cardiac arrests occurred during the last set in the evening.”

Following the tragedy, Scott released a statement promising to pay for victims’ funerals, assist with the investigation and provide therapy to those affected. Scott said in a video statement on Instagram that he did not realize the extent of the emergency, and noted that he typically stops his concerts so injured fans can reach safety.

“I could just never imagine the severity of the situation,” he said.

But concert attendees said Astroworld security deteriorated within hours of the doors opening around noon on Friday.

Houston Police Chief Troy Finner tweeted that he met with Scott “for a few moments last Friday prior to the main event” and “expressed my concerns regarding public safety.” Finner said Scott’s head of security was also at the meeting, which was “brief and respectful.”

Houston disc jockey Michael Pierangeli, 30, who was attending Astroworld for the third time, arrived shortly before noon and said he noticed people sneaking in.

“A lot of people didn’t have wristbands,” signifying they had tickets, he said.

During afternoon shows, Pierangeli said the crowds felt unsafe.

“The vibe was just off,” he said. “It wasn’t actually mosh pits. People were just pushing each other. Walls were getting made and people were getting sucked in. I’m normally in the mix. I just realized it was too much.”

By 2 p.m, hundreds of fans had breached a VIP entrance, just as they breached an area at the last Astroworld in 2019. But police got the area under control and decided not to shut anything down.

“They made some arrests there and they handled that issue,” Peña said.

Eight people died and 25 were hospitalized after crowds surged at the Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival in Houston on Friday.

At about 4:30 p.m., Morbidelli, the EMT, said he started feeling overwhelmed by the density of the crowd as Houston rapper Don Toliver appeared on a smaller stage.

“I ended up grabbing my sister in a bear hug and pushing our way out of the crowd to a barrier and I lifted her up and over,” he said.

Another man in the crowd said he forced his way to the front of the crowd, where security had to lift him over a fence to escape.

At about 8:30 p.m., a countdown appeared on the concert’s big screen, ticking down the minutes to the show. As the crowd pressed in, Madeline Eskins, 23, an ICU nurse who lives north of Houston, fainted. Her boyfriend got someone to help him lift her up in the air and the crowd surfed her, unconscious, over a fence into a less crowded VIP area where she awoke to find emergency personnel woefully unprepared.

People were trying to hop over the fence. Security guards were dropping off more people — some bleeding from their noses or mouths — and then returning to pluck more people from the crowd.

One young man’s eyes rolled back into his head.

“Has ANYBODY checked a pulse?” Eskins yelled to a security guard, and she heard him say no.

Eskins checked the man’s pulse and shone a flashlight in his eyes: no response. She instructed the security guard to take him out of the VIP area for urgent medical assistance. She saw other security guards bring in bodies, including three in cardiac arrest, she said. A handful of medical staff were on site — not nearly enough to aid the seriously injured, she said.

When she asked for an automated external defibrillator, an electronic pad used to treat heart attacks, a medic said they only had one and gestured to a woman whose

shirt was ripped open as other medics gave CPR.

As Eskins gave CPR to a man struggling to breathe, she asked a member of the event medical staff to check his carotid or femoral pulse, but he didn’t know how.

“Travis acknowledged that someone in the crowd needed an ambulance and was passed out,” Eskins said. “He just kept going.”

The chaos accelerated as Scott took to the stage and launched into his first track: “Escape Plan.”

The on-site investigator at the deadly 1979 Who concert said that festival seating and crowd density may have contributed to the Astroworld tragedy.

“Within the first seconds of the first song, people began to drown — in other people,” Seanna Faith McCarty, 21, a festival-goer from the Houston suburb of Katy, wrote on Instagram. “The rush of people became tighter and tighter.”

Gasping for breath, McCarty and her friend, Taylor Grace, realized they had to get out. But there was nowhere to go. As the shoving became more intense, “people began to choke one another as the mass swayed,” she wrote. “Our lungs were compressed between the bodies of those surrounding us.”

Seeing security just a few feet away in a walkway, McCarty and other festival-goers began to scream.

“Hundreds of people ripped their vocal cords apart screaming for help, but we were not heard,” she wrote. “One person fell, or collapsed … A hole opened in the ground. It was like watching a Jenga Tower topple.”

McCarty said she lost sight of Grace and was pushed away from a rail and into the crowd of people, toward the edge of a sinkhole of people. She looked down at a man’s face — only to lose the face in what she described as a “floor of bodies” with “two layers of fallen people above them.”

At one point, McCarty lost her balance and nearly fell. She yelled to a man, who pulled her up. Eventually she was able to get to the back of the crowd. A man pulled her over a guardrail and she spotted a cameraman on an elevated platform, eyes fixed on the stage.

She climbed a ladder and pointed to the hole, telling him people were dying. He told her to get off the platform. Another man grabbed her arm and told her he would push her off the 15-foot platform if she didn’t get down.

“I was in disbelief,” she wrote. “Here were two people that could actually do something. Had the power to do something. Cut the camera, call in backup, pause something. They did nothing.”

A video of the incident went viral over the weekend.

At the same time, as Morbidelli performed CPR on a breathless woman, two concert medical staff in red shirts appeared with a backboard and no other life-saving equipment. One attempted to take over compressions, he said, but “it was very obvious that he was inexperienced at CPR. He was doing it very shallow and way too fast. One of the bystanders even told him to slow down. Once that happened, the medic yelled to see who knew CPR. And I stepped in and took over again.”

“I wasn’t sure what their plan was, so I just snapped,” Morbidelli said. “I yelled to one of the medics to get ready to put her on the backboard, so she was ready to be moved and we were not wasting any time. We rolled her onto her left side, pushed the backboard under her and rolled her on. And that’s when I realized the backboard had no straps. I was shocked.”

A group of officers in bulletproof vests arrived and attempted to lift the woman on the backboard over a barricade, he said.

“Usually, there’s someone who’s at the head of the patient coordinating the lifting and transport. There was none of that. They balanced her on the barricade. But there was some miscommunication between the people at the head of the backboard and the people at the feet of the board, and the patient fell,” he said. “It was like slow motion. I watched her fall and hit the ground. I just fell to my knees and started crying.”

The woman was later identified as 22-year-old Texas A&M senior Bharti Shahani. She remains in intensive care at Houston Methodist Hospital, a spokeswoman said Tuesday.

“Dropping her like that was an act of pure negligence. That is the worst thing that can happen to anyone in the emergency medical field,” Morbidelli said.

Peña said event medical staff were “quickly overwhelmed.” At 9:38 p.m., he said local officials declared a mass casualty event, sending in SWAT, paramedics and several dozen ambulances to treat concertgoers who had collapsed.

Yet Scott continued to perform.

“Everybody that’s there has a responsibility, even the artist. They have the stage, they have the microphone, they have the attention of the crowd,” Peña said, noting that, “at one point there was a pause, maybe when the ambulance was trying to drive through the crowd,” when Scott could have “turned on the lights and said I’m not going to continue the show.”

Instead, Pierangeli said he watched Drake join Scott onstage as an ambulance parked in the crowd trying to treat the injured.

“Kids were standing atop the ambulance, dancing, while obviously the ambulance is trying to save people,” he said.

Nine-year-old Ezra Blount attended the concert with his father, Treston Blount, who was holding the boy on his shoulders.

“He kept saying he couldn’t breathe, he couldn’t breathe and he passed out,” said Treston Blount’s mother, Tericia Blount, 52, a retired nurse in Humble, Texas.

She said Ezra “got trampled a lot. He’s dealing with a lot of severe injuries at this time. He has swelling in the brain, most of his organs have been damaged, he had cardiac arrest.”

“He’s a survivor. With God’s help, he can pull through,” Blount said. “There are a lot of other people who are still in the hospitals and we’re thinking of them, too.”

Lina Hidalgo, chief executive for Houston’s Harris County which owns NRG Park, arrived at 1:30 a.m. and met with families searching for lost loved ones. She has since called for an independent investigation into what went wrong.

“There should be a more detailed plan somewhere,” she said. “Was there anything more systemic that needed to be done better? Is the plan supposed to be so vague? There needs to be a question of was this tragedy a result of circumstances beyond the control of those involved?”

Hidalgo noted that Astroworld organizers’ plans didn’t show where security guards were deployed or how many were in the crowd.

“I don’t know how quickly everybody knew that people were dying. The plan says people are supposed to be in communication, but were the communication lines open enough?” she asked. “There was a recognition that there had been an incident at the concert. When did they know?”

Hidalgo said she spoke Monday with the county medical examiner, who told her it will take weeks to get toxicology results, determine the victims’ causes of death and whether there was foul play.

“There’s families, all of these people wanting answers: the community, the country. And they deserve them,” she said. “If there’s something that needed to be done better, that needs to be addressed ahead of other events.”

Randall Roberts contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.