Nerve agents, poison, window falls: Many Kremlin foes have been attacked or killed

- Share via

TALLINN, Estonia — The attacks can be exotic — poisoned by drinking polonium-laced tea or touching a deadly nerve agent — or more conventional if still brutal, such as getting shot at close range. Some victims take a fatal plunge from an open window.

Over the years, Kremlin political critics, turncoat spies and investigative journalists have been killed or assaulted in a variety of ways.

None had been known to perish in an air accident. But on Wednesday, a private plane carrying Wagner mercenary boss Yevgeny Prigozhin, who staged a brief rebellion in Russia, plummeted tens of thousands of feet into a field after breaking apart.

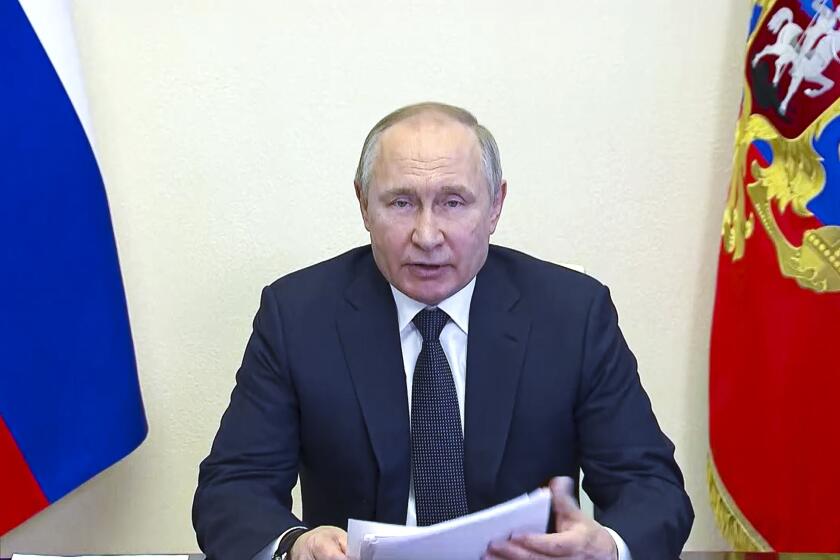

Assassination attempts against foes of Russian President Vladimir Putin have been common during his nearly quarter-century in power. Those close to the victims and the few survivors have blamed Russian authorities, but the Kremlin has routinely denied any involvement.

There also have been reports of prominent Russian executives dying under mysterious circumstances, including falling from windows, although whether they were deliberate killings or suicides is sometimes difficult to determine.

Some prominent cases of documented killings or attempted killings:

Attacks on political opponents

In August 2020, opposition leader Alexei Navalny fell ill on a flight from Siberia to Moscow. The plane landed in the city of Omsk, where Navalny was hospitalized in a coma. Two days later, he was airlifted to Berlin, where he recovered.

His allies almost immediately said he was poisoned, but Russian officials denied it. Labs in Germany, France and Sweden confirmed that Navalny was poisoned by a Soviet-era nerve agent known as Novichok, which he alleged had been applied to his underwear. Navalny returned to Russia and was convicted this month of extremism and sentenced to 19 years in prison, his third conviction with a prison sentence in two years on charges that he says are politically motivated.

Putin finally speaks about Russian mercenary Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin, who is presumed to have died in a plane crash after staging a failed coup.

In 2018, Pyotr Verzilov, a founder of the protest group Pussy Riot, fell severely ill and also was flown to Berlin, where doctors said poisoning was “highly plausible.” He eventually recovered. Earlier that year, Verzilov had embarrassed the Kremlin by running onto the field during soccer’s World Cup final in Moscow with three other activists to protest police brutality. His allies said he could have been targeted because of his activism.

Prominent opposition figure Vladimir Kara-Murza survived what he believes were attempts to poison him in 2015 and 2017. He nearly died from kidney failure in the first instance and suspects poisoning, but no cause was determined. He was hospitalized with a similar illness in 2017 and put into a medically induced coma. His wife said doctors confirmed that he was poisoned. Kara-Murza survived, and his lawyer says police have refused to investigate. This year, he was convicted of treason and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

The highest-profile killing of a political opponent in recent years was that of Boris Nemtsov. Once deputy prime minister under President Boris Yeltsin, Nemtsov was a popular politician and harsh critic of Putin. On a cold February night in 2015, he was gunned down by assailants on a bridge adjacent to the Kremlin as he walked with his girlfriend — a killing that shocked the country. Five men from the Russian region of Chechnya were convicted, with the gunman receiving up to 20 years, but Nemtsov’s allies said their involvement was an attempt to shift blame from the government.

Former intelligence operatives

In 2006, Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, a former agent for the KGB and its post-Soviet successor agency, the FSB, felt violently ill in London after drinking tea laced with radioactive polonium-210, dying three weeks later. He had been investigating the shooting death of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya as well as the Russian intelligence service’s alleged links to organized crime. Before dying, Litvinenko told journalists that the FSB was still operating a poisons laboratory dating from the Soviet era.

A British inquiry found that Russian agents had killed Litvinenko, probably with Putin’s approval, but the Kremlin denied any involvement.

Germany says proof of Soviet-era nerve agent was found in tests on Alexei Navalny, an opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Another former Russian intelligence officer, Sergei Skripal, was poisoned in Britain in 2018. He and his adult daughter Yulia fell ill in the city of Salisbury, in England, and spent weeks in critical condition. They survived, but the attack later claimed the life of a British woman and left a man and a police officer seriously ill.

Authorities said they both were poisoned with the military-grade nerve agent Novichok. Britain blamed Russian intelligence, but Moscow denied any role. Putin called Skripal, a double agent for Britain during his espionage career, a “scumbag” of no interest to the Kremlin because he was tried in Russia and exchanged in a spy swap in 2010.

Slain journalists

Numerous journalists critical of authorities in Russia have been killed or suffered mysterious deaths, which their colleagues in some cases blamed on someone in the political hierarchy. In other cases, the reported reluctance by authorities to investigate raised suspicions.

Anna Politkovskaya, the newspaper journalist for Novaya Gazeta whose death Litvinenko was investigating, was shot and killed in the elevator of her Moscow apartment building Oct. 7, 2006 — Putin’s birthday. She had won international acclaim for her reporting on human rights abuses in Chechnya. The gunman, from Chechnya, was convicted of the killing and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Four other Chechens were given shorter prison terms for their involvement in the murder.

Yuri Shchekochikhin, another Novaya Gazeta reporter, died of a sudden and violent illness in 2003. Shchekochikhin was investigating corrupt business deals and the possible role of Russian security services in the 1999 apartment house bombings blamed on Chechen insurgents. His colleagues insisted that he was poisoned and accused the authorities of deliberately hindering the investigation.

Facing stiff resistance in Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin is using language that recalls the rhetoric of Stalin’s show trials of the 1930s.

Yevgeny Prigozhin and his lieutenants

Wednesday’s plane crash that is presumed to have killed Prigozhin, the chief of the Wagner private military company, and some of his top lieutenants came two months to the day after he launched an armed rebellion that Putin labeled “a stab in the back” and “treason.” While not critical of Putin, Prigozhin had slammed the Russian military leadership and questioned the motives for going to war in Ukraine.

On Thursday, a preliminary U.S. intelligence assessment found that the crash, which killed all 10 people aboard, was intentionally caused by an explosion, according to U.S. and Western officials. The officials spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to comment. One said the explosion fell in line with Putin’s “long history of trying to silence his critics.”

In his first public comments on the crash, Putin appeared to hint that there was no bad blood between him and Prigozhin. But former Kremlin speechwriter-turned-political analyst Abbas Gallyamov said: “Putin has demonstrated that if you fail to obey him without question, he will dispose of you without mercy, like an enemy, even if you are formally a patriot.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.