Pompeo’s pending visit to Pakistan may have prompted the Taliban to report death of leading militant

- Share via

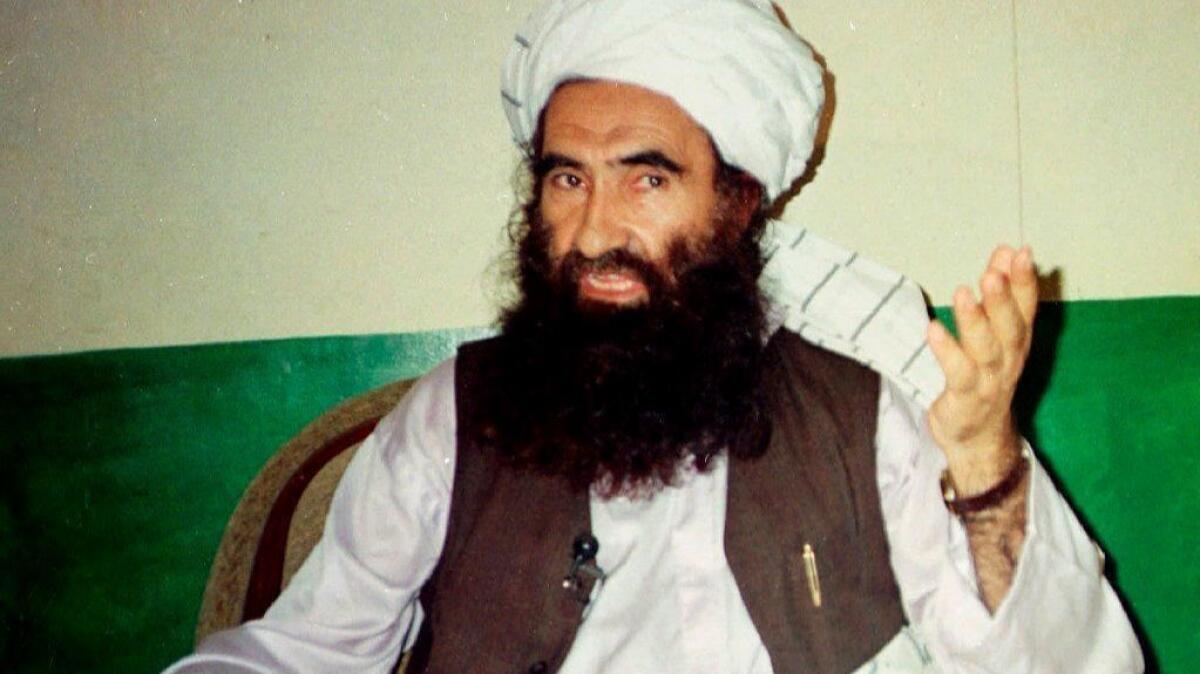

Reporting from Islamabad, Pakistan — Jalaluddin Haqqani, founder of the militant group that has carried out some of the deadliest attacks against U.S.-led coalition forces in Afghanistan, was unofficially reported dead in 2014 and hadn’t been seen publicly since well before that.

Meanwhile, his son had risen into the top ranks of the Taliban.

The Taliban’s announcement Tuesday that Haqqani had died after a long illness confirmed one of the worst-kept secrets of the Afghan war, raising speculation about why the insurgent group decided to go public now.

One explanation could be Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo’s expected arrival on Wednesday in Pakistan, where he will discuss the Trump administration’s efforts to begin direct talks with the Taliban for the first time in the 17-year conflict.

The Haqqani network, as Haqqani’s group is known, is widely believed to enjoy sanctuary in the tribal belt of Pakistan, whose security establishment has long been accused of nurturing the Taliban and other militant groups that wage attacks across the border in Afghanistan.

The Trump administration has withheld hundreds of millions of dollars in security funding in an effort to increase pressure on Pakistan to crack down on militancy and help bring Taliban leaders to the negotiating table.

Pakistan denies that it supports such groups. But analysts said the Taliban could have announced Haqqani’s death at the behest of Pakistan, which has been stung by Trump’s criticism and the loss of U.S. funds.

Rahmatullah Nabil, Afghanistan’s former spy chief, tweeted that the Taliban’s timing suggested Pakistan was “playing as usual.” Many Afghans believe Pakistan is trying to buy time while Taliban insurgents continue to inflict casualties on Afghan forces.

“One reason this announcement has been made now could be to hint to the American public that [the] Haqqanis could possibly be more open to negotiations with U.S. and ending the war in Afghanistan, now that Jalaluddin is officially dead,” said Faran Jeffery, deputy director of Islamic Theology of Counter Terrorism, a British think tank that launches this month.

“It is unlikely that this will prove to be true, but Taliban and their allies probably intended to send that message.”

The news was unlikely to alter the fighting in Afghanistan, which has grown deadlier during Haqqani’s long absence. His son Sirajuddin has risen to become the Taliban’s deputy commander, helping to lead a resurgent militant group that now controls more Afghan territory than at any point since 2001.

In recent months, the insurgents have continued to threaten major cities even as the Trump administration tries for the first time to begin direct talks with the group to end the conflict in Afghanistan.

Haqqani was a former ally of the CIA who had close ties to the Pakistani military establishment and his opposition to U.S. forces since their 2001 invasion of Afghanistan would be seen as “golden chapters of history which future Islamic generations shall forever be proud of,” the Taliban said in a statement.

The statement gave no details of when or where he died, but a source close to the insurgent group — who was not authorized to speak to the media — said he died and was buried in Afghanistan.

Haqqani long enjoyed the support of Pakistani military intelligence, which saw him as an ally in the war against Soviet forces in Afghanistan during the 1980s. The CIA is widely reported to have financed Haqqani during this period as the U.S. deepened its covert Cold War activities in Afghanistan.

A friend of Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden when he was hiding in Afghanistan, Haqqani allied with the Taliban government that took over the country in 1996, serving as its minister for tribal affairs until the 2001 U.S.-led invasion drove the group from power.

His followers quickly became some of the Taliban insurgency’s most effective fighters. They are widely believed to have been behind the 2009 suicide bombing at a U.S. military base in Khost province that killed seven CIA officers and a daylong siege of the U.S. Embassy and North Atlantic Treaty Organization headquarters in Kabul in 2011.

In 2011, Adm. Michael G. Mullen, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called the Haqqani network “a veritable arm” of Pakistani military intelligence. Western officials have long accused Pakistan of supporting Islamist proxies to undermine its neighbors, Afghanistan and India.

After the Taliban’s founding leader, Mullah Mohammad Omar, died in 2013, the Haqqanis “became the only group with the cohesion, influence and geographic reach” to help Pakistan achieve this aim in Afghanistan, according to Stanford University’s Mapping Militants Project.

Two of Haqqani’s sons were killed fighting, one in a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan, according to Mushtaq Yusufzai, a journalist in the Pakistani city of Peshawar who has covered the militant group.

Although Haqqani’s death had been rumored for years, the Taliban might also have waited to confirm it in order to give Sirajuddin a chance to emerge from his father’s shadow, Yusufzai said.

“He might have been termed as inexperienced and might not have been taken that seriously,” Yusufzai said. “But now nobody can question his credentials as a commander and leader.”

Special correspondent Sahi reported from Islamabad and Times staff writer Bengali from Mumbai, India.

Shashank Bengali is South Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.