What it’s really like to grow up Black among the white elite, in two bracing books

- Share via

On the Shelf

Black Struggles in White Spaces

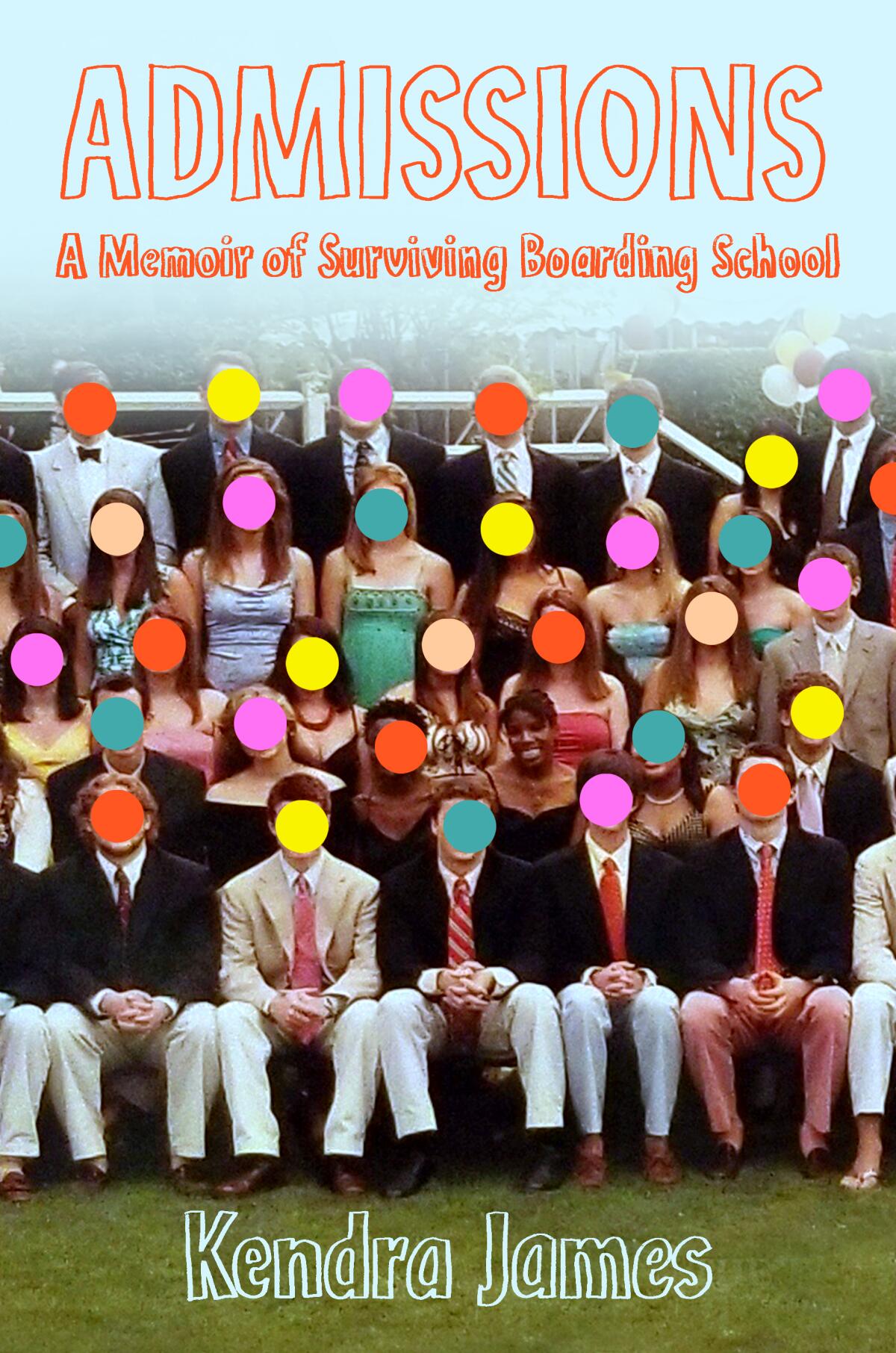

Admissions: A Memoir of Surviving Boarding School

By Kendra James

Grand Central: 304 pages, $29

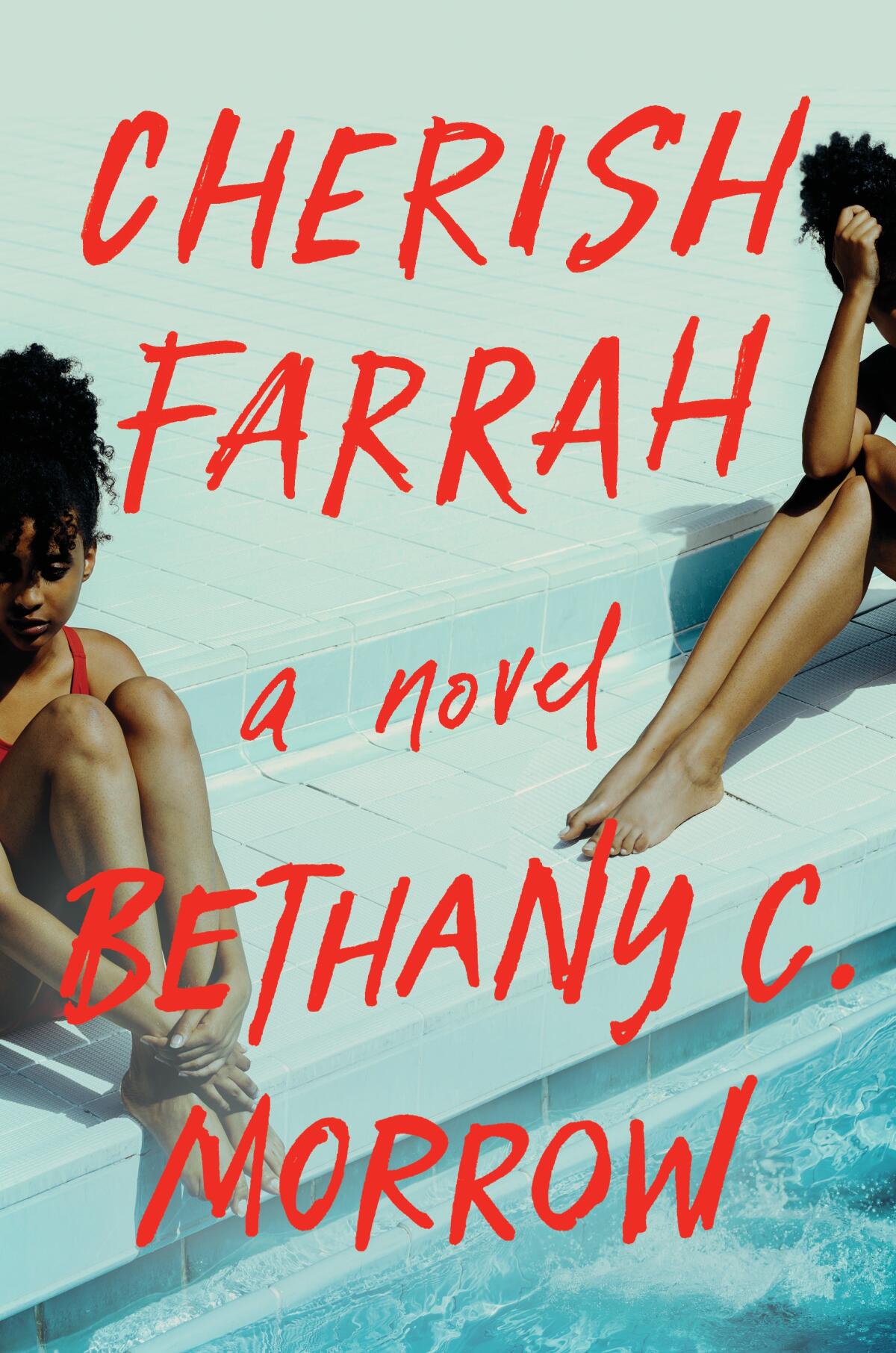

Cherish Farrah

By Bethany C. Morrow

Dutton: 336 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The myth of colorblindness contends that anyone can thrive in America: All we need to do is give underserved groups access to existing structures of power and the rest will work itself out. Two new books eviscerate that concept, examining from very different angles the warping effect that predominantly white institutions can have on young Black women.

Kendra James’ debut, “Admissions: A Memoir of Surviving Boarding School,” begins with a glossary. That choice might seem strange for a contemporary story set in the suburbs of Connecticut — not a place the average American reader would expect to need a translator. But it doubles as an announcement that James is taking us into the kind of clubby, insular culture where familiar-sounding words have been repurposed as a code intelligible only to a privileged few.

James attended the Taft School in Watertown, Conn., from her sophomore year of high school, beginning in 2003, until she graduated in 2006. Her father was an alum, and he had frequently brought the family to campus for visits. James was, she writes, “the first Black American legacy student to graduate from The Taft School” since it started admitting Black students less than 50 years earlier.

During her time as a student, she reacts to that fact with “bitter pride” that eventually becomes “mortification” at being singled out for public discussion. One of the book’s key questions comes to her only later in her life: Why did so few of the other Black Americans who’d attended Taft want to send their children there?

Aside from a few flash-forwards to James’ post-collegiate work in private-school admissions, the memoir unfolds chronologically, beginning with an orientation for new students of color and ending with graduation. Much like the glossary, this feels intentional: It teaches us the language and culture of Taft alongside James, allowing us to bear witness as her naivete about certain aspects of race, class and power turns into knowing — and to gain a sense of what that knowledge costs.

The book is, not incidentally, an excellent memoir. James is unsparing and hilarious about her adolescent foibles, her outré fashion choices and insistence on telling everyone about her hobby of writing erotic fan fiction. Many former intense young nerds will cringe with loving recognition.

Deesha Philyaw talks about the long gestation of her collection ‘The Secret Lives of Church Ladies,’ a Times Book Prize finalist for first fiction.

James’ generosity toward her younger self extends to everyone she writes about, even the classmates whose racism she describes. Ultimately, she seems less interested in indicting them than in thinking about the system of exclusive education that has encouraged their myopia about race and class — about any lives markedly different from their own— to flourish unchecked.

Of that first orientation, she writes, “No one was saying the words ‘race,’ ‘privilege,’ ‘Black,’ ‘Latinx,’ or ‘white’ aloud; I wasn’t yet at the point where I thought I needed to ask why being not white at Taft in 2003 would be such a big deal.” (If those subjects aren’t discussed explicitly at a meeting for students of color, she adds elsewhere in the book, you can imagine how often the school broached it with the white kids: exactly once a year, during Black History Month.)

The emotional climax of James’ memoir is a devastating chapter on the aftermath of an op-ed in the school paper written by a white student, who accuses minority students of being “the real segregationists” on campus. Two minority student groups call a meeting to figure out how to respond, and James finds herself taking minutes on the proceedings.

No faculty members attend; no adults guide or aid them as they try to wrangle their grief, pain and fury at being accused of separating themselves from a community that was not built with them in mind. “It was just us,” James writes, “ten children sitting in a room, surrounded by whiteness on all sides, attempting to solve the racism of a 115-year-old institution.”

They didn’t, of course. How could they have? Instead, James has written a must-read book for prospective prep-school parents as well as white graduates seeking to better understand what these kinds of elite schools can offer their students — as well as what they, by their very nature, cannot.

……

Bethany C. Morrow’s “Cherish Farrah” shares some surface themes with “Admissions.” It begins as a contemporary story about a pair of Black girls who live in an otherwise white country club community, a world of lavish and thoughtless privilege. But soon the novel spirals into the dysphoric and surreal, ultimately turning into the kind of unnerving social horror Jordan Peele popularized in his 2017 film “Get Out.”

Morrow is the author of six novels, including “A Song Below Water” (2020), which was a finalist for the Locus Awards. Her writing is often, though not always, speculative; “Cherish Farrah” is a rare example of fairly straightforward realism. Still, it’s shot through with its narrator’s destabilizing visions and occasional hallucinations, which make its world feel queasily, feverishly strange. It is a book about teenagers but it is decidedly not a young-adult novel.

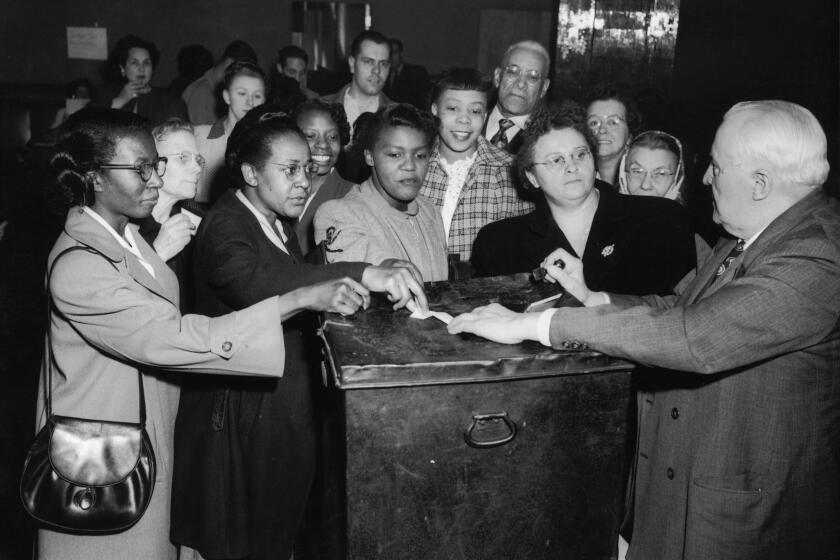

Remember the names Fannie Lou Hamer, Constance Baker Motley and Mary McLeod Bethune. Vice President Kamala Harris does, as does historian Martha S. Jones.

The story begins in the bedroom of Cherish Whitman, the Black adopted daughter of white parents who have raised her to be what her best friend, our narrator Farrah Turner, also Black, calls “white girl spoiled.” Farrah describes the condition: “adored to the point of coddling to the point of infantilization to the point of arrested development.” It is, she acknowledges, a dangerous thing for a Black girl to be.

Farrah is living with the Whitmans because her own world has recently been upended: Her mother lost her job and her parents’ house has been foreclosed on. Having grown up among the unimaginably wealthy, Farrah is stunned to learn the difference between her parents’ relatively new money and the fathomless cushion of white generational wealth. “I had a list of ways my home didn’t measure up to places like the Whitmans’,” she notes, “back when I didn’t know that houses could be lost.”

It’s a particularly striking moment because Farrah prides herself on being several steps ahead of everyone else — even the adults. Her narration is cold and calculating, alternately marked by disdain and paranoia; her watchword, repeated like a chorus throughout the book, is “control.” She fantasizes about hurting even the people she loves. When she and Cherish go for an unsanctioned dip in her old home’s pool, Farrah imagines “how blood might plume in the illuminated water.”

But she is not the only dangerous one in this story, and as her stay with the Whitmans unfolds she begins to see that their motives for having her in their daughter’s life aren’t as pure as they’ve led her to believe — but also that her sister-bond with Cherish is stronger than they understand.

“Cherish Farrah” is a psychological thriller, and part of its tension comes from trying to guess whether Farrah will snap before the Whitmans’ trap does. That also means, however, that we spend so much time in Farrah’s mind that it becomes difficult to feel plot momentum build or to separate what’s actually happening from her elaborate imaginings. Farrah’s internal world is so baroque that the final plot twist seems almost tame in comparison — though the book’s last scenes leave the reader with the feeling that they’ve just been through the wringer regardless.

“Cherish Farrah” is not a book for the faint of heart. Skin burns and bones break; wounds fester and suppurate. A tongue gets bitten out of someone’s mouth. The book is at once restrained and ferocious; like Farrah, it maintains control until it can’t anymore, and then it erupts. Morrow uses her heroine’s warped perspective to examine painful truths about race and class in America, but this isn’t a book intended to teach anyone a lesson, except maybe: Be careful. You never know who’s really in control.

Amazon’s ‘Them’ and Oscar nominee ‘Two Distant Strangers,’ which mix racist violence and genre elements, have ignited a debate over ‘trauma porn.’

Romanoff is a writer and the author of several novels for young adults.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.