What the Houston Astrodome can teach us

- Share via

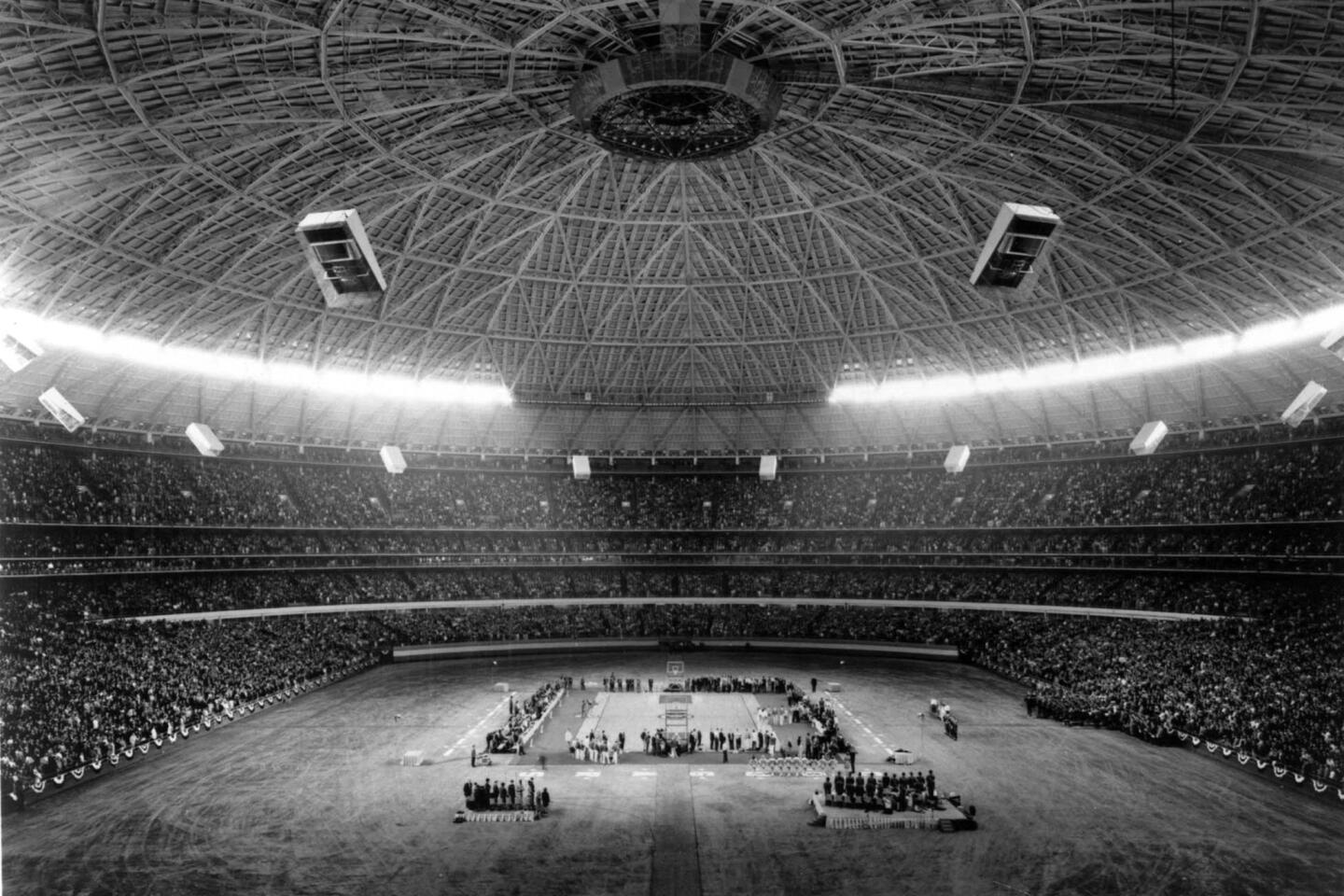

Now that voters have rejected a plan to save the Houston Astrodome, a marvel of engineering muscle and space-age glamour and easily the city’s most important building, it would be easy to conclude that modern architecture has a major image problem in this country.

That idea is underscored by the sad fate of Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, a striking clover-shaped concrete tower designed by Bertrand Goldberg that Northwestern University has begun demolishing to make room for a $370-million biomedical research center. And by threats to important buildings on the East Coast by the architect Paul Rudolph.

But it’s not all of modern architecture that has an image problem. For the most part, the great landmarks of modern architecture from the 1920s through the 1950s have earned enough admiration among the public to give them a substantial measure of protection. This is even true, mirabile dictu, in Los Angeles.

What is coming under acute threat is a particular subset of modern architecture: significant buildings designed in the 1960s and 1970s, just as the movement was losing its supreme, heavy-footed global influence and splintering into a number of competing factions. The Astrodome was completed in 1965 and Prentice in 1975. Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center in New York state, which has so far survived a serious demolition threat, opened in 1970.

What is it about late-modern designs that has left them so vulnerable in recent years? In part it’s simple arithmetic. Works of architecture tend to fall out of fashion beginning around age 25 and hit their deepest levels of disfavor between 40 and 50 years old. This is largely true regardless of architectural style or historical period. Buildings, it turns out, experience their own version of a midlife crisis.

New York’s Pennsylvania Station, a vast, stately example of Beaux-Arts neoclassicism by the firm McKim, Mead and White, opened in 1910. It was first threatened with demolition around 1955, at 45 years old; a three-year demolition process began in 1963, when the building was 53.

Irving Gill’s Dodge House, a triumph of early Los Angeles modernism, was completed in 1916 and razed in 1970, a span of 54 years.

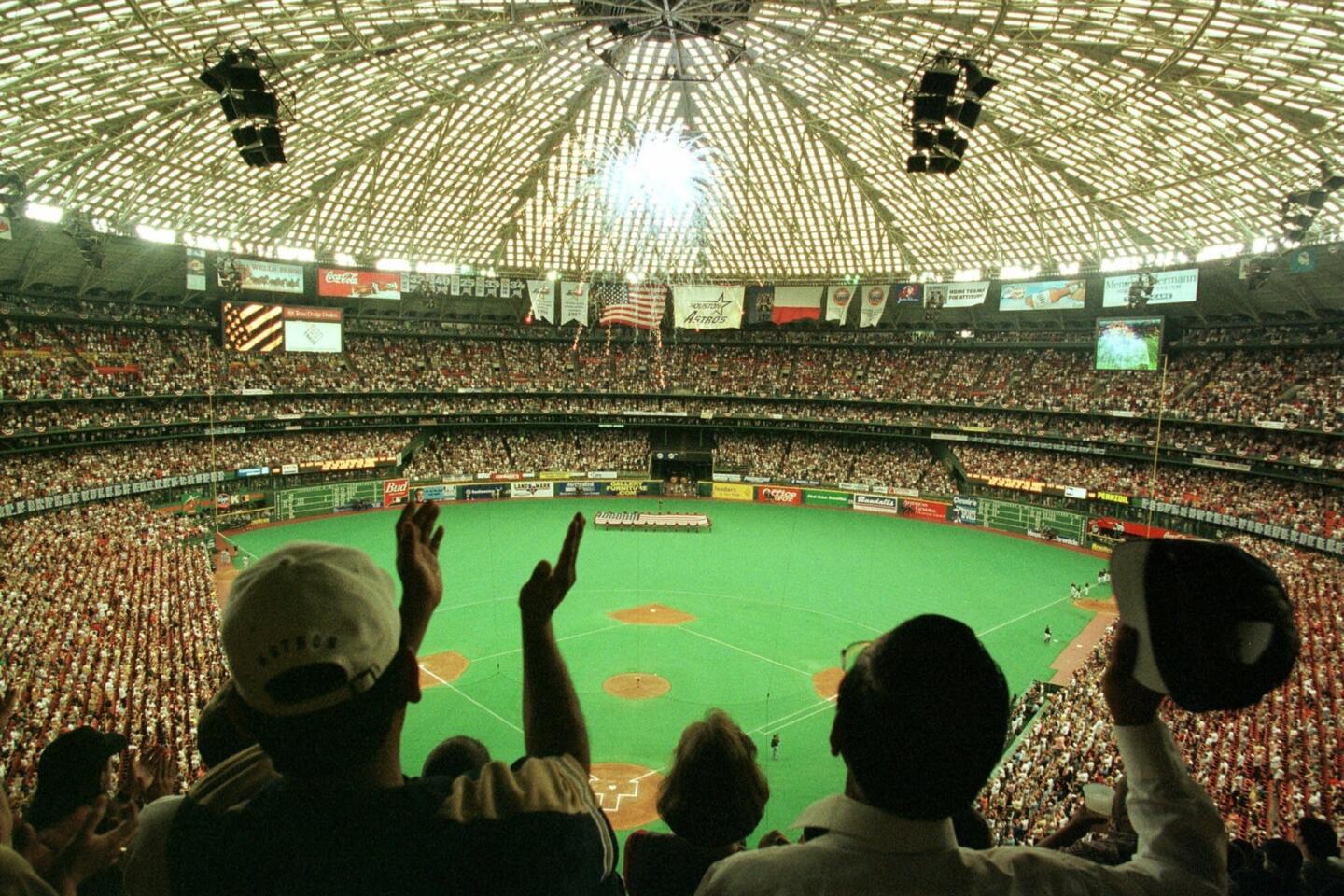

The math looks nearly identical for the Astrodome. It has been empty since 2009, the year it turned 44. It now seems unlikely to see its 50th birthday.

INTERACTIVE: Tour Los Angeles’ boulevards

But the threat to late-modern architecture in this country has other sources. Chief among them is the manner in which modernism broke apart in the 1960s and 1970s. A movement that had been remarkably steadfast, prizing novelty and spare geometry while rejecting ornament and overt references to architectural history, turned dramatically pluralistic.

Architects like Edward Durell Stone, Minoru Yamasaki and William Pereira stayed loyal to parts of modernist doctrine while introducing hints of decoration. Others, including Rudolph and Goldberg, built tough, flinty buildings in the style known as Brutalism, which took its name from the French phrase béton brut, or raw concrete.

And even as these architects were pursuing these new strands of modernism, others were trying to topple the movement altogether. Michael Graves, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown pioneered a historically minded, slyly ironic approach that became known as post-modern architecture. Sim Van der Ryn and other architects on the West Coast sowed the seeds of eco-conscious sustainable design.

The dominant theme of this period in architecture was the lack of a dominant theme. There was suddenly great appeal in straying from consensus, in bucking prewar modernism’s great and ultimately crushing certainty.

That makes what’s happening now particularly vexing for preservationists. Since much of the architecture from that era was pointedly tough or complicated or even openly ambivalent about its place in the culture, rallying support for it among the public can be tricky. While we sympathize quite easily with a novelist or a painter who wants to resist the dictates of the marketplace or mass taste with work that is prickly, harsh or darkly poetic, we rarely give architects the same creative leeway.

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

The Astrodome, to be clear, is not a doubt-filled building in that way. Its confidence in the rightness of its approach — and in its ideal of canned, controllable nature — was unshakable.

But it was arguably the last of the prominent high-modern buildings in this country. As such it represents not just the high point but the beginning of the end for a certain attitude and approach.

While the Astrodome was being planned and built, American culture was beginning to chip away at ideas its architects and champions took for granted, especially American dominance over a vast political sphere of influence and the natural world. Books including Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” Jane Jacobs’ “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” and Venturi’s “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” were published between 1961 and 1966.

Each book, in its own way, undermined the idea that a domed, climate-controlled modern stadium built in the center of a huge parking lot made cultural or environmental sense.

The Astrodome therefore makes a fascinating if complex test case for the current health of the American preservation movement. It is the buildings produced on the heels of those revolutionary books, the dome’s rebellious children, that will be increasingly threatened over the next decade or so.

And the battle to save them will run uphill. It is hard to imagine any Brutalist building — even one by Rudolph, a true master — winning anything close to the 47% support the dome earned on Nov. 5. The same is true of the tough-minded early experiments of the so-called L.A. School, a group of architects including Frank Gehry, Eric Owen Moss, Michael Rotondi and Thom Mayne.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

So how can preservationists adapt?

To begin with, they’ll need to accept that winning public support for late-modern buildings will be difficult and sometimes impossible. It will be necessary for them to pick their spots and make tough, even seemingly Solomonic choices.

Take two buildings from 1965 just as an example: The fight over the Astrodome is far more important than the one over Pereira’s original Los Angeles County Museum of Art campus on Wilshire Boulevard, however much Pereira’s work deserves the fresh attention it is now getting.

In addition, preservation campaigns will have to be more carefully and strategically run. The one for Proposition 2, the county bond measure that sought to raise $217 million for the Astrodome, was badly mismanaged.

The measure was quietly slipped onto an off-year ballot that was guaranteed to draw low interest and attract a disproportionate number of older, antitax voters. (Turnout was 13%.) Had Astrodome supporters waited until next fall and promoted their cause better and more widely, Proposition 2 would likely have passed by a wide margin. That, in turn, would have buoyed preservationists around the country in their efforts to protect major late-modern landmarks.

Most important of all, finally, is a new emphasis among preservation groups on proactive campaigns. There should be an outcry not just when buildings are threatened by demolition but when their basic upkeep or architectural dignity is in question.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

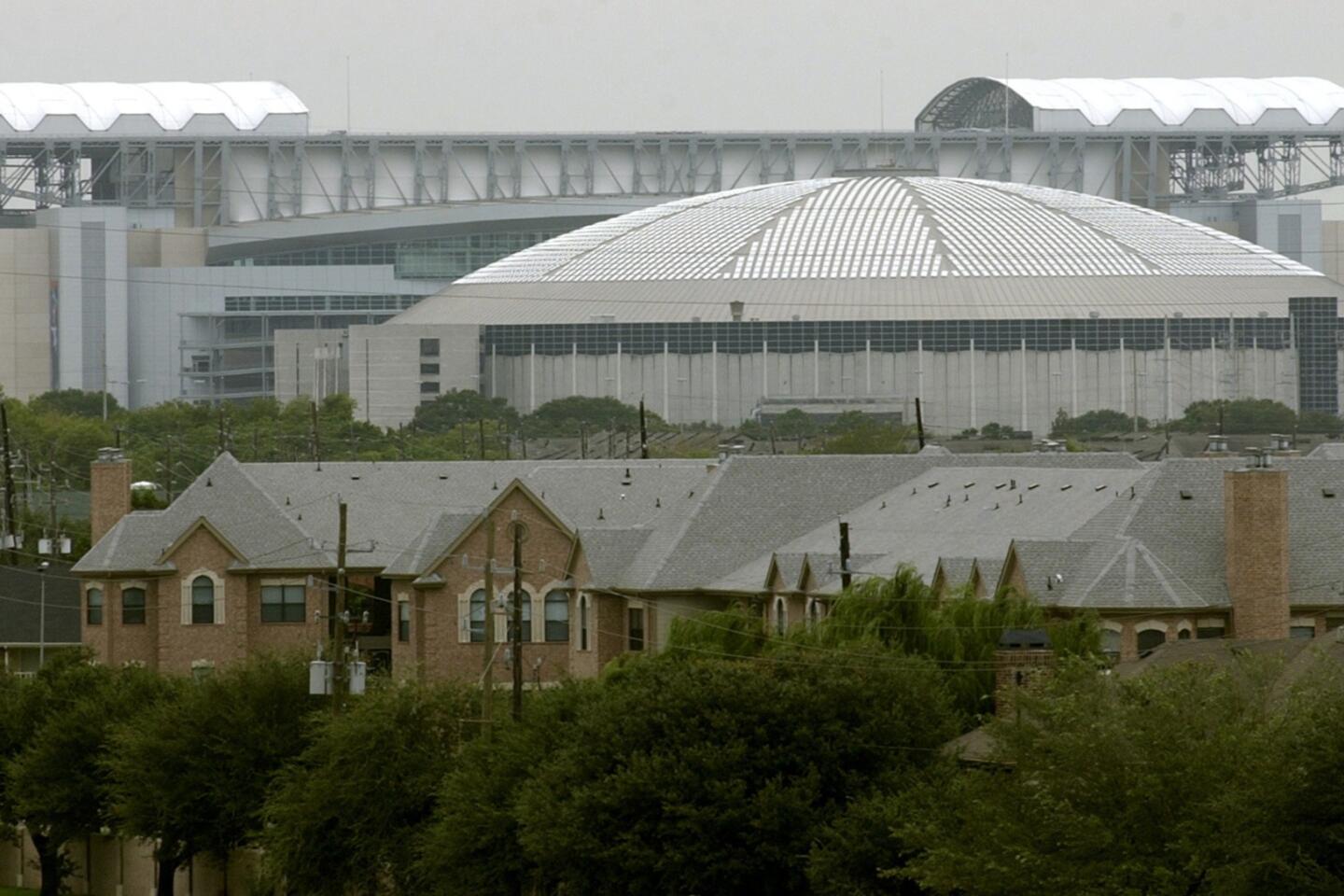

The Astrodome’s fate may have been sealed not on the day baseball’s Astros moved out after the 1999 season but when Reliant Stadium, home to the NFL’s Texans, was built basically right on top of the dome, just a couple of hundred feet away, in 2002. The hulking new stadium looks as if it is elbowing the smaller Astrodome out of the way. Local and national preservation groups should have insisted that the dome be given more breathing room. Without it the building looks more like an afterthought than a landmark with a proud and important history.

Proactive advocacy also means getting out ahead of the curve of taste and educating the public about precisely the architectural movements they find most deeply unfashionable. Right now that means focusing on signal achievements in architecture from the late 1960s through the 1980s.

Prewar modern, Case Study modern, “Mad Men” modern, Googie modern, space-age modern: These architectural categories have grown as popular as they are ever going to be. On the flip side, it may already be too late to turn Brutalism’s reputation around.

Instead, it’s time to introduce a broad American public to names like Charles Moore, John Portman, Craig Hodgetts and Ming Fung, Franklin Israel, Kevin Roche, Anthony Lumsden and Gunnar Birkerts. It’s time to concentrate on building up support for the mirrored-glass, tongue-in-cheek neoclassical and exposed-joint L.A. School experiments of the Nixon, Ford, Carter and Reagan years.

They are fast slipping into the preservation danger zone.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.