Doll cheek tint, car paint and other secrets revealed in the Getty’s Latin American art study

- Share via

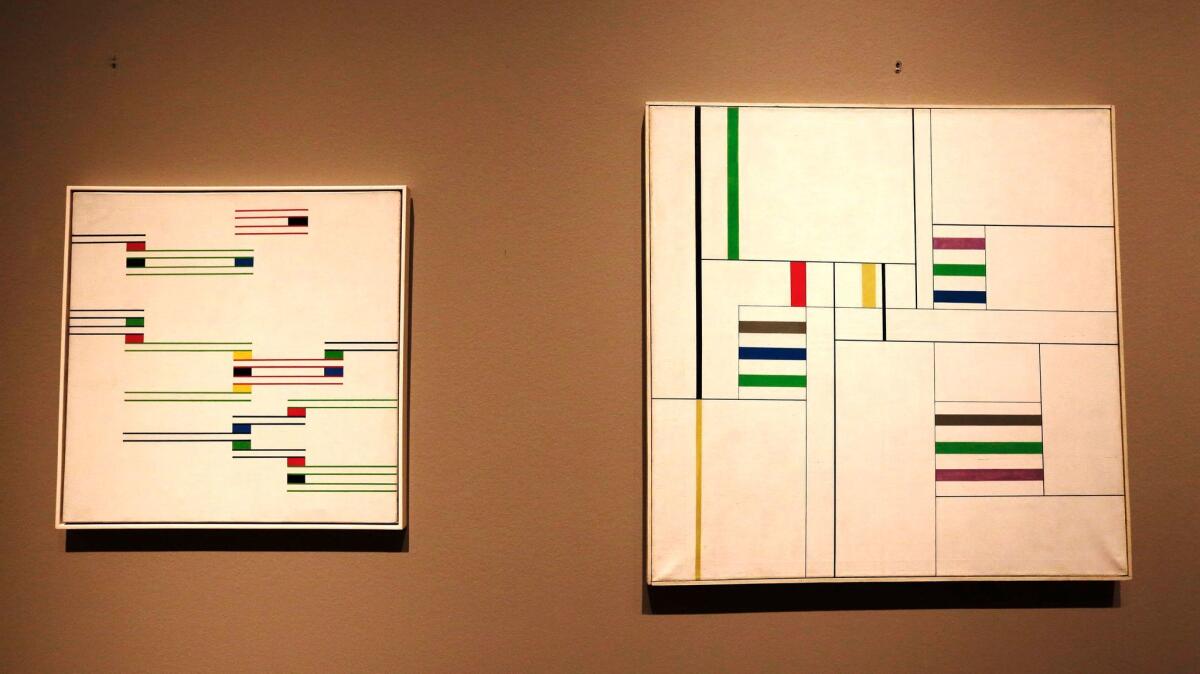

Hanging in a gallery at L.A.’s Getty Center are more than a dozen canvases and other works produced in South America by a key clutch of Modernist artists. This includes a delicate, curling sheet-metal assemblage from the late 1950s by Brazilian abstractionist Lygia Clark, as well as a composition of colorful floating shapes, made in the ’40s, by the Argentinean Raúl Lozza.

But the works are not on public view. At least not yet.

Instead, the 17 pieces — all owned by prominent Venezuelan collector Patricia Phelps de Cisneros — are only on view for study by conservators and historians at the Getty (and beyond). The idea is to better understand how art from this era was made and how it might best be preserved.

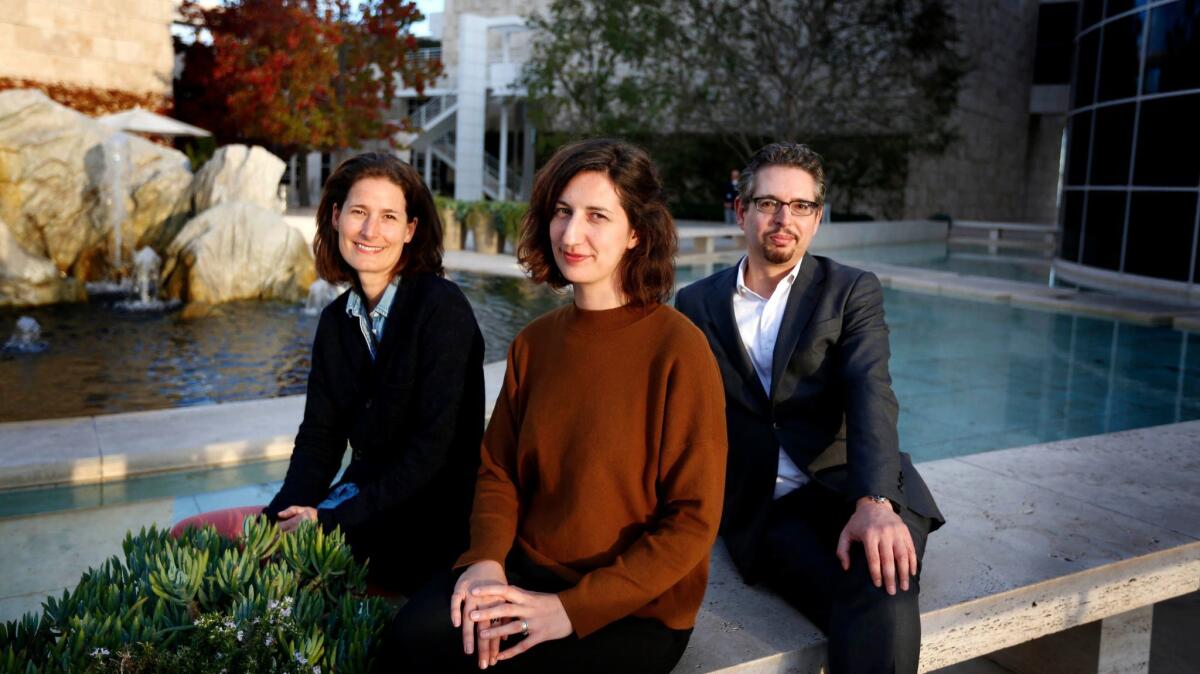

“What we are trying to do is not just have this be science and conservation,” says Andrew Perchuk of the Getty Research Institute, one of the Getty branches involved in the project. “But it’s to see what the new types of imaging and analysis also reveal about an artist’s process and methods.”

The research shows the decisions the artists made about paint — which often has just as much bearing on a work as the composition.

— Pia Gottschaller, of the Getty Conservation Institute

Next year, the works and some of the findings will be presented to the public in “Making Art Concrete: Works From Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros,” as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time exhibition series devoted to Latino and Latin American art — known as PST LA/LA.

This intensive scientific research helps build a body of knowledge about work that doesn’t often get a lot of airtime in conservation labs. (Works by Jackson Pollock have been studied to death; Argentinean Modernists, not so much.)

“We have partners in Argentina and Brazil,” says Zanna Gilbert, a research specialist working on the project at the Getty Research Institute. “We share our findings with them.”

The project was inspired by other Getty programs that have combined conservation and historical research — as was done with Pollock’s 1943 canvas “Mural,” which the museum methodically studied, documented, conserved and exhibited in 2014. This not only helped conservators address problems afflicting the work, it helped determine how Pollock created the piece, providing a better understanding of his development as an artist.

Hoping to do something similar for next year’s PST LA/LA exhibitions, the Getty approached Cisneros, renowned for her holdings in 20th century Latin American art, about studying pieces in her collection. She agreed.

The information boom comes at an opportune time since many U.S. institutions have been showing greater interest in acquiring and displaying art from beyond the U.S. and Europe. Cisneros recently donated more than 100 works of Latin American art to New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

The Argentinean and Brazilian paintings and wall sculptures at the Getty — by artists representing avant-garde South American movements from the ’40s and ’50s — have been examined under microscopes, with ultraviolet light and infrared reflectography. These methods can reveal obscured layers and long-forgotten retouchings. Conservators have even taken microscopic cross-sections of paint on some pieces, to determine the materials used.

Already some interesting discoveries have been made. A 1952 canvas by influential Brazilian painter Geraldo de Barros is made with unusual combinations of paint and urethane — “a mix you don’t get normally,” says Pia Gottschaller of the Getty Conservation Institute.

The nature of the materials led the group to interview the artist’s daughter, who told them her father regularly associated with a Hungarian chemist who worked on tints for plastics (he made his money figuring out how to give doll cheeks their rosy hue). This anecdote provided valuable insight into Barros’ working methods and the ways in which he experimented with industrial and other materials.

Likewise, on the small, black-and-white steel sculpture by Clark, titled “Casulo No. 2,” the team discovered car paint. The piece is from 1959, before car paint was widely used in art in the United States, making Clark an important pioneer.

“The research helps us show what these groundbreaking works were made from,” says Gottschaller, “and it shows the decisions the artists made about paint — which often has just as much bearing on a work as the composition.”

The information will be key to preserving these works for future generations.

“The thing with modern paints is that it can be anything,” Gottschaller says. “You really have to do this kind of analysis to figure it out.”

This will ultimately aid in the works’ conservation. Says Perchuk: “Certain solvents will clean one paint and disintegrate another.”

More significantly, it supports study in little-known areas of art history.

“I think it’s fair to say,” says Gottschaller, “that most of these works have never been examined in this way.”

“Making Art Concrete” opens at the Getty Center in August 2017.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Artist Marnie Weber reflects on why monsters hold such power for women

What happens when two artists move into an unfinished museum for 10 days of ‘Performance Lessons’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.