Review: At the Ojai festival, an erratic dance with the West’s composers

- Share via

OJAI — — Reputed to court mavericks, the Ojai Music Festival doesn’t always extend a very large welcome mat. But this offbeat weekend, the mat was massive.Attention was drawn to supposedly kooky and bizarrely neglected West Coast composers who happen to be essential contributors to American music and our national identity.

It was choreographer Mark Morris’ festival — Ojai’s first music director from the dance world — and it was a mess, a gloriously revelatory and ingratiating mess at its best. At its worst, well, we’ll get to that. But you’ve got to break some eggs to make a Western omelet. At least the ingredients were locally sourced and, although certainly not to all tastes, exceedingly fresh.

There were, over four days, 37 events. This was no longer the traditional Ojai Festival escape to a spiritual, alluring valley. If you hoped to savor a sunset “pink moment,” reflect in one of the valley’s radiant meditation sites or take a hike, you’d have done better to have found another weekend.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Festival 67 was, instead, Ojai boot camp. Down enough drinks to get up the courage to sing karaoke in a Mexican restaurant with Morris and the jazz trio Bad Plus until 3 a.m. Head for the hills at dawn for a hangover-cure sunrise concert while Ojai’s fog lifts along with your own. Dash to the city’s Libbey Park for 9 a.m. warm-up (that is to say, killer) exercises with dancers from the Mark Morris Dance Group preceding late morning performances.

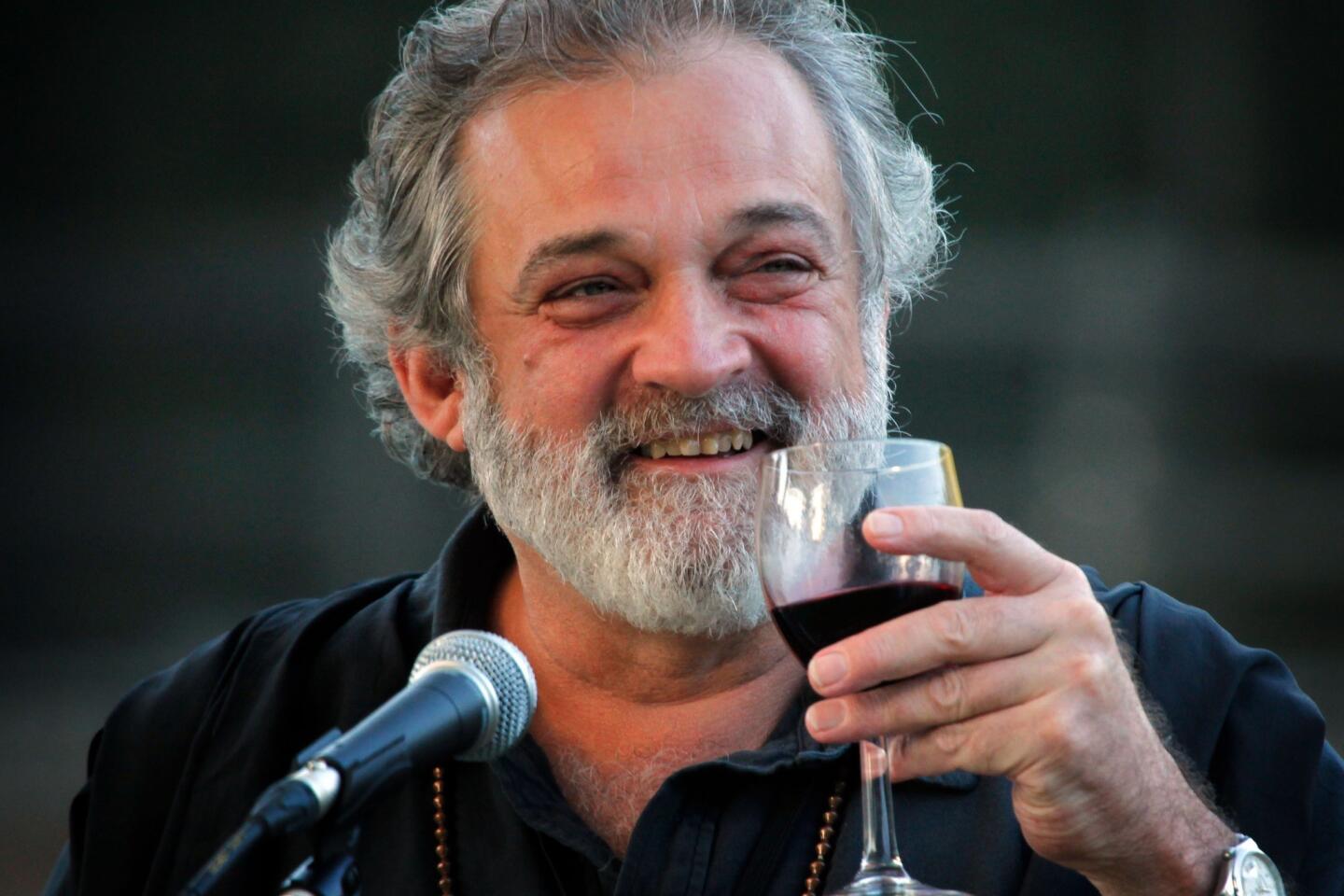

At one festival reception, Morris — dressed night and day, on stage and off, in shorts, socks and sandals — mandated social dancing. When intimidated waltzers got flustered, he barked, “It’s not an emergency, it’s a dance.” He was bossy, insulting, infuriating, illuminating and hilarious. Morris also displayed such a moving, loving, insightful sense of music that new worlds of wonder opened before a listener’s eyes — yes, eyes, because there was dance as well as music.

What this festival ultimately will be remembered for is Morris’ determined advocacy of Henry Cowell and Lou Harrison. Cowell, who was born in Menlo Park in 1897, almost single-handedly evolved a free-spirited, exceptionally wide-ranging California style, one until then unprecedented in the history of music. He was an ultra-modernist who was also a sentimental Romantic, an eclectic who was the first composer to make a systematic study of the world’s musical cultures. (He invented the whole notion of world music.)

The festival traced a line from Charles Ives to Cowell (who was an early champion of Ives) to Harrison and John Cage (who studied with Cowell) to John Luther Adams (who was close to and influenced by Harrison). To accommodate so much, Morris’ programming was exceedingly free ranging.

CHEAT SHEET: Spring Arts Preview

There was just one Mark Morris Dance Group program at Libbey Bowl, on Friday night. It demonstrated the more classical sides of Ives, Harrison and Cowell. The most recent dance was “Jenn and Spencer,” which Morris premiered earlier this spring in New York and which uses Cowell’s Suite for Violin and Piano. It is a 1926 suite of sweet neo-Classical and Celtic beauty. Violinist Michi Wiancko and pianist Colin Fowler played it rapturously. Morris’ effusive mobile geometry was, as ever, on display in this pas de deux for Spencer Ramirez and Jenn Weddel, but so was an unusual elegant and refined sexuality.

The same year that Cowell wrote this astonishing suite he began his indescribably strange ballet “Atlantis,” for three singers and instrumental large ensemble, which helped close the festival Sunday night. The score has never been choreographed, but Cowell provides a soundtrack for the birth, trials and tribulations and ravishment of a Sea Soul. The explicit moans, wails and groans of amazement that Cowell asks for from the soloists are probably better learned at porno shoots in Encino than in music schools. Unfortunately, soprano Yulia Van Doren, mezzo-soprano Jamie Van Eyck and baritone Douglas Williams too obviously faked their orgasms, sounding more as if they were reacting to a cold shower. Joshua Gersen conducted the MMDG Music Ensemble with rhythmic acuity but not sensuality. Still, with a little imagination you got the point.

Harrison, who spent much of his career in the Santa Cruz area and who died a decade ago, was the weekend’s agent of enchantment. He could be seen as a bewitching presence in a Saturday afternoon screening of Eva Soltes’ 2012 documentary, “Lou Harrison” A World of Music.” The Harrison world of music was, like Cowell’s, global. Gamelan Sari Raras, a Javanese ensemble that uses traditional Indonesian instruments collected by Harrison, gave outdoor concerts under a gazebo (and Morris and a handful of his dancers joined, momentarily, as singers).

There were Harrison disappointments. The Symphonic Suite for Strings, conducted by Gersen, sounded thin and lacked Harrison’s sweet sensuality. But Gersen and the Red Fish Blue Fish percussion ensemble, with Fowler as soloist, provided a strong punch to Harrison’s Concerto for Organ and Percussion Orchestra late Sunday afternoon. The festival ended that evening with Harrison’s Concerto for Piano and Javanese Gamelan. The piano is tuned to accommodate that of the gamelan, and that paves the way for an alternate universe of nonstop splendor.

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by The Times

John Luther Adams’ “For Lou Harrison,” the big piece Saturday night, was also nonstop. For an hour, an ensemble of strings and two pianos appear to climb up a scale, over and over in a huge procession that clearly drove many in the audience crazy. But the gorgeous textures are subtly varied, offering those willing to give in an exhausting, never-ending stairway to paradise.

Ives was well treated in a program of Ives and Cowell songs (performed by the same vocalists as the soloists in “Atlantis”), his organ Variations on “America” (Fowler) and his trio (Wiancko, cellist Wolfram Koessel and Fowler). His Second Quartet was duller (the American String Quartet).

Cage, in all this, was left out in the cold. Late night concerts at Ojai are dark and chilly. Cage’s hour-long “Four Walls” for piano, with a brief soprano interlude, is a problematic work. A score to a Merce Cunningham dance, it was put away and forgotten about after its single performance in 1944, and the composer reluctantly would have liked it to stay that way. But he couldn’t stop the music from re-entering the repertory in 1985. It has a Satie-esque quality and needs a light, focused touch.

Instead, Ethan Iverson proved a puerile pianist, banging and mugging his way through the hour as though it were all a bad joke. He wore a ridiculous blue cape. Van Doren was required to parade around the piano in a nightdress and bare feet, with clattery objects tied to her ankles.

The ensemble Red Fish Blue Fish was at least respectful the next night in a Cage percussion program, but it was again late and cold and the playing was more dutiful than exciting.

The group, however, more than made up for that early Sunday morning with Adams’ “songbirdsongs” at Meditation Mount, overlooking the Ojai valley. Percussionists and piccolo players imitated bird song. The sun came out. The birds came too. You couldn’t ask for anything more. This was Ojai in all its enlightenment.

Next year the pianist Jeremy Denk will be the music director and the direction will change, as it does every year, radically.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.