Buffalo Bill Cody would be proud

- Share via

CODY, WYO. — It started with a single sculpture -- a rifle-toting, horse-riding bronze of Buffalo Bill Cody by New York artist-heiress Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

Now, the Whitney Gallery of Western Art -- located in Cody’s namesake community just east of Yellowstone National Park -- is marking its first half-century with a sweeping reinstallation. The Whitney name stands as a reminder that it was made possible with Eastern largess, the same behind New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

“We used to kid about how to build a western museum with eastern money, but it was basically true,” said former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson, chairman of the gallery’s parent institution, the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. With the museum’s funds now increasingly from western donors, Simpson said, “that old slogan doesn’t work anymore.”

True to the museum’s roots, works by “cowboy artists” such as Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington are just steps away from one of the world’s most comprehensive gun collections, the Cody Firearms Museum.

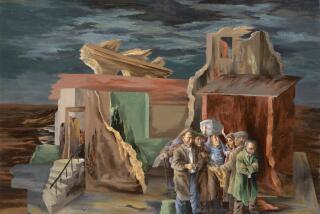

Like the Colt six-shooters up the hall, the Whitney Gallery derives its reputation largely from iconic visions of a West frozen in time. The paintings and sculptures betray a nostalgia for a world now past, populated with pioneers and Indians and complicated by winter storms, stampeding cattle and aggressive bears.

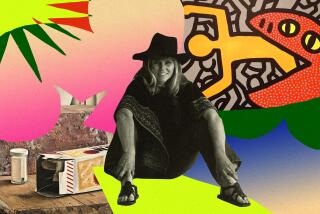

In crafting the reinstallation, curator Mindy Besaw tried to push the genre to new heights. She mixed and regrouped artists, styles and media to transform what had been a conventional artistic survey -- driven by chronology -- into a thematic story told in the colors and textures of the West.

“You’re never going to get a white canvas with a blue square on it and call it western art,” Besaw said. “But there’s something about the West that’s always going to be magical or powerful for people if you want to reminisce about a simpler time. It’s wonderful out here, and there’s something about the paintings that remind people of that.”

For years after Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s 1929 donation, her sculpture stood on an otherwise empty lot at the edge of town. Next door was a small cabin that housed some of Buffalo Bill’s memorabilia.

Bankrolled by a $250,000 donation from Whitney’s son, Cornelius, the gallery opened in 1959. It bucked the going trend within eastern and European art circles that favored Abstract Expressionism, typified by Jackson Pollock.

By contrast, western art offered something uniquely American. Art historian Peter Hassrick called it a “foil from the tyranny of abstractionism.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.