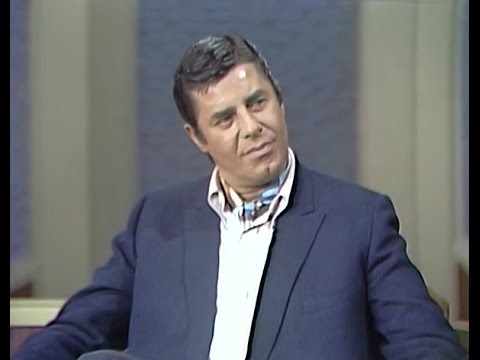

Commentary: A stage comedian and movie star, Jerry Lewis was also very much a man of television

- Share via

Jerry Lewis, who died Sunday at the age of 91 having survived a smorgasbord of ailments that individually would have killed other mortals, was first and foremost a movie star and filmmaker — one of a handful of comedians who might reasonably be called an auteur. But he also had a long life on television, as a performer, a game-show guest, a talk-show guest, a talk-show guest-host, a talk-show host, a three-time Oscars host and the name-above-the-title animating spirit of the Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day Telethon, that yearly marathon over which he presided like a mad rabbi, priest and wizard.

Lewis began his TV career began with a bang in 1950, alongside partner Dean Martin, with NBC’s “The Colgate Comedy Hour.” Many episodes may be found online, and they are something of a revelation. Working against painted backdrops with a minimum of props, they played characters, or themselves, or some cross between the two. Norman Lear and Ed Simmons were their writers, and many of the sketches, with Dean as a more or less responsible adult and Jerry as some form of child or man-child, might have been the premise of a Martin-and-Lewis feature film — a stowaway situation, a backstage comedy.

What you also get, in spades, is the ferocious energy of their anarchic nightclub act. (Martin: “Let’s do something sort of ad lib now.” Lewis: “What do you think I’ve been doing for the last 40 minutes?”) In a recurring opening bit, they are booked to play some inappropriate event — a librarians’ convention, a meeting of morticians. They run on, kicking up their legs, clapping their hands, leaping about, setting themselves against propriety. They are physical in a way that seems a little impertinent now, and might have then. Lewis, especially, is all over the stage, getting right up in the camera to confidentially address an audience of tens of millions: “You get the idea – I’m supposed to be a 9-year-old kid.”

After his break with Martin, Lewis headlined the odd variety special and was an interim host of “The Tonight Show” between Jack Paar’s departure and the arrival of Johnny Carson. (Temporary sidekick Hugh Downs: “Working with you is a pleasure, Jerry. It’s not restful, but it’s a pleasure.”) But his attempts at hosting his own series all failed.

The first, for ABC in 1963, which involved the Lewis-directed renovation of the old El Capitan Theater on Vine Street in Hollywood (later the Palace, and now the Avalon), was a spectacular, as in spectacularly expensive, flop. Later, less costly adventures on NBC (1967) and in syndication (1984) did a little better and even worse, respectively.

He was a great guest host, perhaps, because as a host he was also was a guest — a special attraction. But a successful full-time host needs to be able to fade at least temporarily into the background, and Lewis was never less than fearsomely present, even during the years when he was addicted to painkillers in the 1970s. Lewis was too much of a muchness, possibly, too intense, too serious, too confusing a person to sustain a regular spot in the medium.

In later years, apart from the occasional acting job (a five-episode arc of “Wiseguy” stands out) and the Labor Day telethon, Lewis’ main TV work was as an interview subject. (When he sat down with Dick Cavett in 1973 for a long, serious talk about filmmaking, his career as a filmmaker was effectively over.) He was on with Carson, David Letterman, Conan O’Brien, Larry King, Bob Costas, Mike Douglas and Phil Donahue..

He appeared on morning shows, afternoon shows, late-night shows, news shows and chat shows, to be plumbed at greater or lesser depth. Even when medication blew him up to twice his natural size (“I look like a Jew sumo,” he said), even in his last years when his head had sunk down into a valley between his shoulders, Lewis was never out of show business.

Generally, his interlocutors treated him with the respect due a king, and Lewis could be appropriately imperious; yet was also curiously naked and open. He offset his madcap image with a studied elegance, though he would usually find an occasion to stuff something in his ears. He could seem self-justifying and self-searching, intellectual and sentimental all at once, as he improvised, revised and codified the narrative of his life.

Above all, from local events in the early 1950s to the national broadcast he ran from 1966 until 2011, there was the telethon, fundraising as performance art. L. Half-man, half-telethon, he was indivisible from his cause.

Significantly, it was a real-time event — live television, as in the old “Colgate” days, a race against the clock that lasted nearly a whole day. Famously, it was the stage on which he and Martin were together for the first time in 20 years — a reunion engineered by Frank Sinatra, to Lewis’ surprise. “You working?” he cracked to his old partner, after a long embrace.

“The thing that disenchants me,” he told Susskind in 1965, “is when television became an expedient medium rather than an instant medium. The beauty of television is in its term, tele-vision: tell, see now…. Watching that man fall accidentally now. The thing that disillusioned me [is] when it became a packaged medium, put it into a carton and ship it for a later date… Television should be now.”

Follow Robert Lloyd on Twitter @LATimesTVLloyd

The slapstick, the telethons, ‘L-a-a-a-dy!’ — comic and philanthropist Jerry Lewis dies at 91

Video:An interview with comic legend Jerry Lewis

An appreciation: Jerry Lewis helped write the auteur’s playbook

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.