Behind the story: Step into this Tongva classroom and witness love in an act of redemption

- Share via

As a former student of Latin and briefly Middle English, I learned from an early age that language is a time machine, capable of carrying the imagination into the past.

Arma virumque cano — I sing of arms and the man — writes Virgil as he opens the door upon his tale of ancient Rome.

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote — April with its sweet showers — writes Chaucer as he begins his story of pilgrims sojourning to Canterbury.

These poets and countless others captured worlds that have long disappeared, yet their works remain today as compelling and meaningful as when they were originally written.

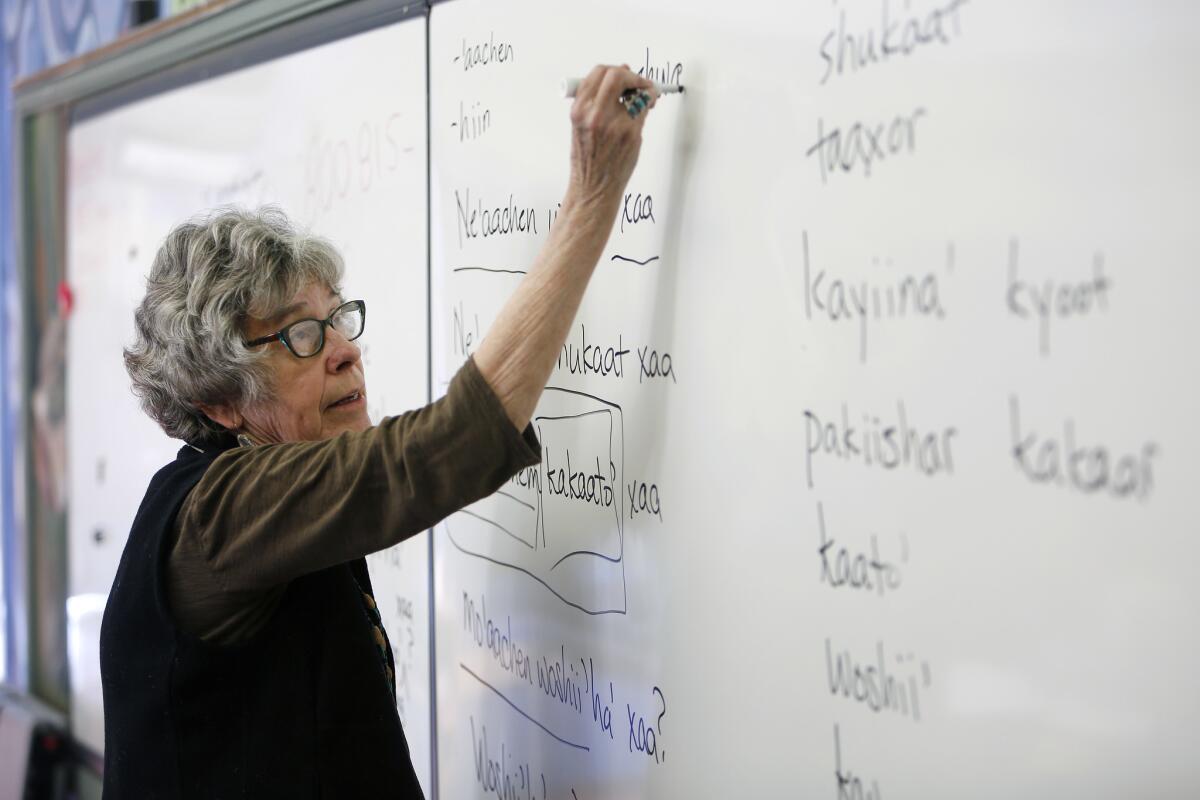

Tongva, the first language of Los Angeles, has no literature written by native speakers, and its last native speaker died by some estimates at least 50 years ago. But after visiting a classroom in San Pedro where instructor Pam Munro laid out her lessons, I fell back in time and caught glimpses of this city — its beauty and tragedy — laid out over time.

Tongva, Los Angeles’ first language, opens the door to a forgotten time and place »

Totoonarom. ‘Isaawtom. Papaashukat.

Pronghorns, wolves and elks no longer roam the L.A. Basin.

Papaa’ishar.

Sea otters swim no more in local kelp beds.

But there they were in the well-practiced enunciation of these students.

“Language,” wrote the novelist Walker Percy, “is the very mirror by which we see and know the world.”

The mirror of Tongva captures a largely unrecognizable world, a world initially changed and shaped by the Spanish upon their arrival in Southern California. It is hard to imagine this flood plain with its communities of indigenous people, harder too to imagine their forced relocation, chillingly captured in this video map.

As much as I thought about these villages, I also considered the land itself, the bayous and the savannas once plentiful here. I even found myself searching for words, like “bayou” and “savanna,” that rarely surface in descriptions of Southern California.

“Freeway,” “suburb,” “beach” are our lingua franca.

Over three classroom visits, I listened as students mastered pronunciation (like the glottal stop — represented typographically by ‘ — which is the sound in the middle of “uh-oh”), as they studied “markers” (suffixes or prefixes added to words to indicate their grammatical function in a sentence) and as they coined new words (“povaakat worooyt,” said one student to a 10-year-old playing with a small toy: “Batman”).

Watching their efforts, I realized that Tongva was not just a link to the past but a living language, animated by their enthusiasm, hopefulness and poignancy of their efforts.

If language is a mirror, then this reflection — even as sunlight poured through the classroom’s open doorway — occasionally darkened. Were it not for the work of Munro, building upon the records of early ethnographers, these lessons would never exist.

“California on the eve of contact with Europeans was an exuberant clamor of Native American economies, languages, tribes and individuals,” Benjamin Madley writes in “An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe.”

But that exuberant clamor soon became a dirge. From 1846 to 1873, an estimated 80% of the California Indian population died.

To look at the old black-and-white photographs of the Tongva consultants — Felicitas Serrano Montano, Mrs. James Rosemyre, Jose Zalvidea — who survived and shared their language with its earliest students, John Peabody Harrington and C. Hart Merriam, is to be filled with sorrow for what once was.

California before the arrival of the Spanish in 1769 was one of the most linguistically diverse places on Earth. Of the 90 or so languages belonging to Native Californians, somewhere between two dozen to 30 are still spoken. Given the private nature of these languages and that no recent survey has been conducted, precise calculations are impossible.

Linguists today are rightly dismayed by this extinction — and by the loss of many languages worldwide.

“English-language dominance in the English-speaking world has achieved and continues to achieve the highest documented rate of destruction, approaching now 90%,” wrote linguist Michael Krauss in 1992. “Surely, just as extinction of any animal species diminishes our world, so does the extinction of any language. Should we mourn the loss of Eyak or Ubykh any less than the loss of the panda or California condor?”

Like the condor, California’s native languages continue to be threatened. Discrimination, shame and the juggernaut of English disseminated in popular culture take a toll. Unlike cuisine, which proudly declares itself and is easily celebrated, language leaves a more complicated mark. As much as it builds communities, it also divides.

In 1998, more than 60% of California voters approved Proposition 227, which eliminated most bilingual instruction in public schools. Eighteen years later, it was repealed. Legislatures in 29 states — including California — have passed resolutions declaring English the official language. Only Alaska and Hawaii grant indigenous languages co-official status.

Los Angeles has been described as a polyglot city. An estimated 120 languages — from Hmong to Q’anjob’al to Korean, French, Russian and Spanish — are spoken here, but as former Times writer Robert Lee Hotz wrote in 2000, language is for some a “portal to wealth, power and attainment,” but for others, it can “break you … box you in, force you down paths you would never have taken.”

Against this recent history, the work of Munro and her students is heroic. Culture thrives on differences, and in this classroom, they gather to create something rich and new and vital.

Munro never called her commitment to teaching Tongva a work of love, but I could think of no better description for this act of redemption.

Twitter: @tcurwen

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.