San Francisco supervisors get behind Laura’s Law mental health program

- Share via

Reporting from San Francisco — A dozen years after state passage of Laura’s Law — which allowed counties to set up programs mandating outpatient treatment of the severely mentally ill — San Francisco supervisors Tuesday vowed to take the matter to voters if a board majority does not approve one by summer.

The law approved in 2002 was named for Nevada County’s Laura Wilcox, who was killed by a man who had been refusing treatment when he entered the county’s behavioral health offices and opened fire.

Though it permitted counties to create programs that impose treatment under court order, it provided no funding and the issue has been so volatile — mental health consumers and advocacy groups oppose forced treatment — that until recently only Nevada County had one.

That may be changing.

Yolo County approved a small pilot program last year. Last week, Orange County’s Board of Supervisors voted to implement one, spurred in part by the brutal beating death of a homeless man suffering from schizophrenia.

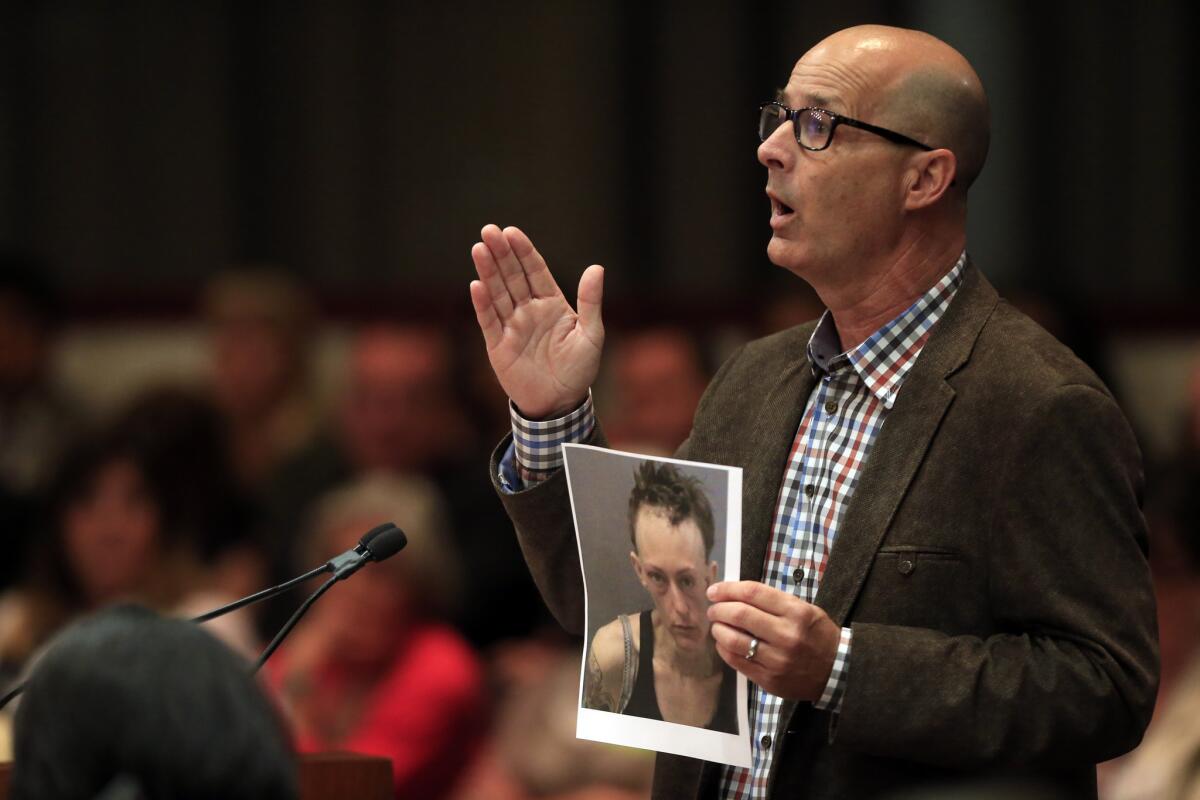

And in San Francisco on Tuesday, Supervisor Mark Farrell announced that he would introduce an initiative ordinance to be placed on the November ballot that would “fully implement Laura’s Law within the city and county of San Francisco.”

Farrell also planned to introduce identical board legislation in hopes of winning over enough votes by August to implement a program without taking the matter to voters.

“Laura’s Law will provide appropriate treatment services for our most vulnerable, reduce hospitalization and incarceration rates, and improve public safety for our residents,” Farrell said in a statement. “If we are truly serious about helping the most vulnerable in our community and ensuring that they are put on a path toward recovery and success, San Francisco cannot afford to stay idle anymore.”

Los Angeles and San Francisco counties have both been operating modified versions of Laura’s Law that are voluntary, but provide the kind of intensive treatment planning and supervision that the legislation envisioned.

Joining Farrell as cosponsors are Supervisors Scott Wiener, Katy Tang and London Breed.

Laura’s Law authorizes counties to set up so-called “assisted outpatient treatment” programs for those who, due to their illness, have rejected voluntary care but have experienced multiple crises such as hospitalizations or jail stints.

Nevada County has significantly reduced hospitalizations and re-arrests under its small program, data shows. Though the program has managed to persuade most clients to participate voluntarily rather than under court order, the court order and authority of the judge serves as an incentive.

“It gets people with severe mental illness engaged in treatment; it saves lives and saves money,” Wilcox’s parents, Amanda and Nick Wilcox, said in a statement. Nevada County implemented its program as part of a settlement of a civil lawsuit with the Wilcox family.

San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee is among those backing implementation here. He said Tuesday: “The proof is what we see on the streets every day in our city with too many people dealing with serious mental health issues like schizophrenia, often self-medicating with drugs and alcohol.”

Dr. John Rouse, attending physician for San Francisco General Hospital inpatient psychiatry and psychiatric emergency services, added at a news conference that many of the urgent psychiatric admissions at the public hospital, as well as many of the 7,300 annual emergency room visits, are attributed to patients who have “unilaterally stopped outpatient treatment.”

The director of San Francisco’s Department of Public Health backs the program as well, as does the police chief, district attorney and fire chief.

The matter is sure to spur controversy. In late February Alameda County supervisors postponed a Laura’s Law decision for three months after emotional testimony.

Among the critics, the San Francisco Chronicle reported, was Christina Murphy, a 35-year-old woman who said she overcame a lifelong struggle with misdiagnosed mental illnesses and overmedication thanks to anger management classes and support groups.

She now works at a Berkeley center that helps mental health patients and told supervisors that forced treatment does not work.

“I want to have a say-so in my recovery,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.