Hepatitis A outbreak declared in L.A. County. ‘We really have to get ahead of this’

- Share via

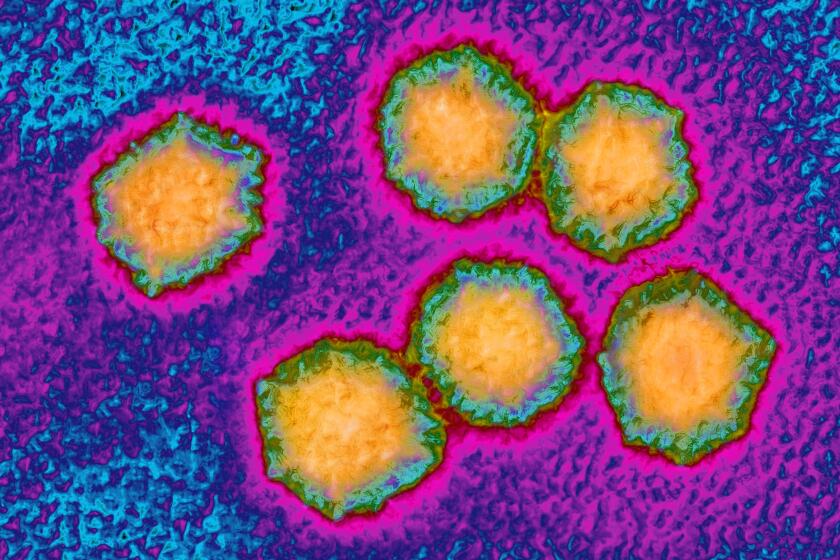

- Hepatitis A is a contagious virus that can be contracted by ingesting contaminated food and drink.

- Getting vaccinated and regularly washing your hands are among the ways residents can better protect themselves.

Los Angeles County has declared a communitywide outbreak of hepatitis A, a highly contagious viral disease that can lead to lasting liver damage or even death.

Although cases of hepatitis A are nothing new in the region, health officials are now expressing alarm both at the prevalence of the disease and who is becoming infected.

The total of 165 cases recorded in 2024 was triple the number seen the year before, and the highest in the county in at least a decade, officials say. Seven deaths have been linked to the now-13-month-old outbreak.

Historically, hepatitis A infections in L.A. County have largely been identified in homeless people, as limited access to toilets and handwashing facilities can help the disease spread more easily, county health officials say. But this year, most infections have been reported among people who aren’t homeless, and who haven’t recently traveled or used illicit drugs, which are other common risk factors.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health it investigating a hepatitis A outbreak among the homeless population.

“The ongoing increase in hepatitis A cases signals that quick action is needed to protect public health,” Dr. Muntu Davis, the L.A. County health officer, said in a statement Monday, urging people to get vaccinated against the disease.

Over the first three months of this year, 29 cases have been reported, double the total seen during the comparable period last year.

The highly contagious virus is found in the stool and blood of infected people, and can be contracted by unknowingly ingesting contaminated food and drink. Using drugs with, caring for or having sexual contact with an infected person are also common means of infection, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of confirmed cases in L.A. County is almost certainly an understatement of the disease’s true prevalence, as infections can go undiagnosed. Even so, this outbreak already far surpasses what had been L.A. County’s most significant hepatitis A outbreak in the last decade, when 87 confirmed cases were reported in 2017.

An ailing inmate worker in the kitchen at Men’s Central Jail unwittingly exposed thousands of detainees to hepatitis A before medical staff discovered what was wrong with him, triggering a vaccination campaign last year.

“We definitely think that the outbreak is bigger than the numbers imply,” said Dr. Sharon Balter, director of the Division of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention in L.A. County. Balter urged healthcare providers to test for hepatitis A if they think a patient’s symptoms are consistent with the disease.

The outbreak has also started to make itself apparent in L.A. County wastewater data, Balter said. Officials had been hopeful that a decline in viral levels in late 2024 suggested the outbreak was easing, but they have started to increase yet again.

Wastewater surveillance gives a better idea of the true scale of hepatitis A’s presence in the community, Balter said, because “many people may not present for care when they’re infected” — either because they’re asymptomatic or they don’t have access to healthcare.

Symptoms of hepatitis A include fever, fatigue, stomach pain, nausea, a yellowing of the skin or eyes, and dark urine. Among adults, infection usually results in symptoms, with jaundice occurring in more than 70% of patients, according to the CDC. Among children younger than 6, about 70% of infections are asymptomatic.

Most people will fully recover from the disease, “but it can occasionally result in liver failure and death,” Balter said.

Officials said they were investigating a reported case of hepatitis A affecting an employee of a Beverly Hills Whole Foods, just days after announcing that several cases had been detected among unhoused people in L.A. County.

Genetic analysis indicates the strain identified in this outbreak has primarily been found in L.A. County, said Dr. Prabhu Gounder, medical director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health’s viral hepatitis unit. A few cases linked to this strain have also been confirmed in Orange and San Bernardino counties.

There is a vaccine for hepatitis A, which was recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for young children starting in 1996 in areas with the highest rates of disease, and then in 2006 for all children.

“The vaccine is very effective,” Gounder said.

The CDC recommends all children be vaccinated for hepatitis A at age 1 or 2. The shots are administered as a two-dose schedule, given at least six months apart. Older children and adults can also get vaccinated.

Getting vaccinated against hepatitis A has never been required as a condition of entry to California’s kindergartens or child-care centers, however.

“This does mean that there’s a large cohort of adults who may not have been vaccinated,” Balter said.

Customers who ate at the Buffalo Wild Wings in Monterey Park on Nov. 13 to 22 should get a hepatitis A vaccine if they aren’t already immunized, health officials said.

Because of the outbreak, the L.A. County Department of Public Health strongly encourages hepatitis A vaccinations for:

- Any L.A. County resident who has not previously been vaccinated and is seeking protection

- People experiencing homelessness

- People using drugs, including non-injection drugs

“It’s a very safe, very effective vaccine. You can get it through your [healthcare] provider, or you can just go to a pharmacy,” Balter said. Millions of hepatitis A vaccination doses have been given since the 1990s, the CDC says.

People experiencing homelessness and people who use drugs “should especially get the vaccine,” Balter said.

If you don’t know whether you’ve been vaccinated, it’s still safe to get — even if it means possibly being vaccinated again.

“You should just go and get vaccinated if you’re not sure,” Balter said.

If you’ve already had both vaccine doses, there is no need to get additional shots, with some exceptions. A bone marrow transplant patient may need to get re-vaccinated, for instance.

Another way to protect yourself is to regularly wash your hands with soap and water, especially after using the bathroom or before preparing and eating food, Balter said.

Experts say San Diego took all the right steps in addressing what is now one of the largest hepatitis A outbreaks the country has seen in decades, but variables unique to the city’s situation contributed to the outbreak.

“If you’re going to use hand sanitizer, really, we’re looking for hand sanitizer that has 60% alcohol or more, and a lot of hand sanitizers don’t,” Balter said, noting that lower-alcohol options don’t always eliminate the virus.

It can take anywhere from 15 to 50 days between exposure and illness, according to the CDC. Mild hepatitis A illness can last one to two weeks, but severely disabling illness can last several months. About 10% to 15% of infected people “have prolonged or relapsing symptoms over six to nine months,” the CDC said.

Because of the lengthy incubation time, “we really have to get ahead of this,” Gounder said. “Right now, what we’re seeing [are cases resulting from] exposure that happened seven weeks ago.”

Hepatitis A can also be challenging to diagnose because early symptoms might be mistaken for gastroenteritis, or stomach flu, Gounder said. More apparent signs of infection, such as yellow eyes, may emerge later — but possibly only after a test for the virus starts showing as negative.

Diseases similar to hepatitis A have been described in records since ancient times, but the virus was isolated only in the 1970s. Hepatitis A was far more common before a highly effective vaccine was licensed for use in the U.S. in 1995.

Hepatitis A case rates fell by 95.5% from 1996 to 2011, according to the CDC, but a resurgence was recorded starting in 2016 “due to widespread outbreaks among persons reporting drug use and homelessness.”

One area that saw substantial spread of the disease was San Diego County, which recorded 20 deaths and 592 cases during an outbreak that started in 2016 and ended in 2018.

The 2017 hepatitis A outbreak in L.A. County “ended with a tremendous effort” by public health officials to provide the vaccine to people who couldn’t get it themselves and to increase public awareness of the disease, Balter said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has notified the California Department of Public Health it is suspending grants it had provided to support the state’s infectious-disease response during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Of the 165 hepatitis A cases in L.A. County last year, most were among adults, officials said. “These are people who probably did not get vaccinated previously, and for whatever reason, weren’t exposed when they were children,” Balter said.

Detecting the scope of the current outbreak through wastewater data has been valuable, officials say. Federal budget cutbacks, however, could affect such services in the future.

“Absolutely, we’re concerned about the impacts of [reduced federal] funding on our ability to protect L.A. County from things like hepatitis A outbreaks,” Balter said.

A recently released federal budget proposal would significantly cut or eliminate a number of grants — such as those for epidemiology laboratory capacity and hospital preparedness, Balter said.

California joined a coalition of states Monday in suing the Trump administration to block sweeping cuts to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“These would really impact our ability to track an illness and, especially, to respond to it. So we are definitely very concerned about that,” Balter said.

Another worry is the threat of reduced funding for vaccines. If funds are cut, “we will lose a substantial source of free vaccines that we need to increase immunity, which is ultimately what needs to happen to stop this outbreak,” Gounder said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.