Blood Feuds Over Lineage

- Share via

SANTA YNEZ, Calif. -- Before the Indian casino opened here, few people had any interest in joining the Chumash tribe.

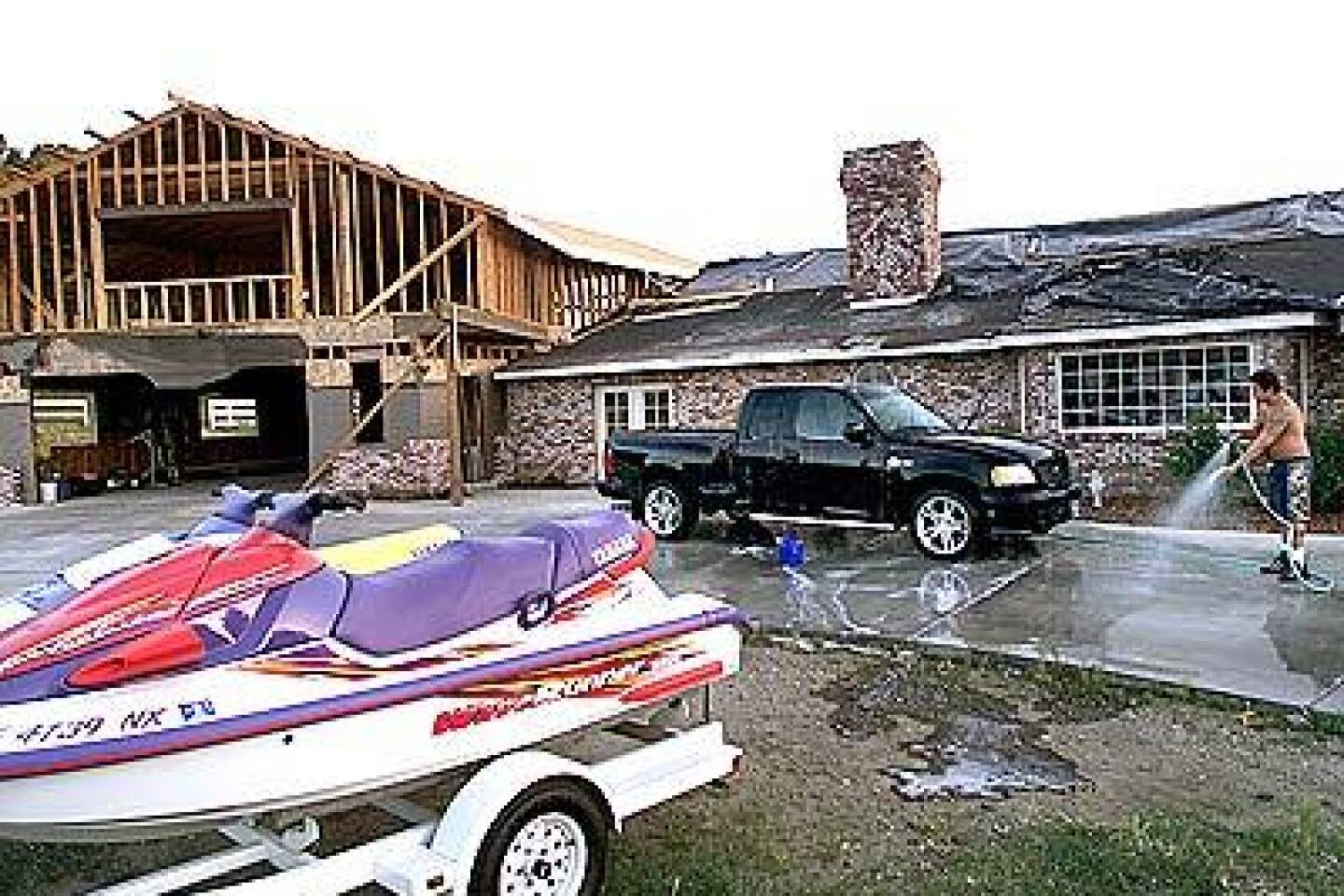

But now that each member collects close to $350,000 a year in gambling revenue, nearly everyone with a drop of Chumash blood wants in.

“A lot of people found out they were Indian,” joked George Armenta, chairman of the Chumash enrollment committee.

Infighting over lineage is tearing apart many tribes with gambling operations. Fueling the disputes is simple math: If tribal enrollment shrinks, each remaining member will collect more money.

In March, the Pechanga Band of Luiseno Mission Indians in Temecula evicted about 130 members of one extended family.

Dozens of members of the Santa Ynez Chumash have faced challenges to their ancestry in recent years.

One member caused an uproar during a 2002 general council meeting when she declared that more tribal members “are not Indian” than are.

Bylaws of the Santa Ynez band require applicants to prove that their ancestors appear on the tribe’s 1940 census roll, and that they possess at least one-quarter “Indian blood of the Band.”

Yet because records are fragmentary, establishing the necessary “blood quotient” can be arduous. Critics contend that decisions on membership are often based on personal and family feuds.

Decades-old records of the government’s Indian Census Roll suggest the difficulty of tracing Chumash bloodlines.

“It is practically impossible to obtain accurate data regarding the Santa Ynez Indians,” states a notation that appears on census reports between 1924 and 1936. “The parish priest for these Indians stated that there were but few of the tribe that he called genuine Indians, the others being mixed bloods, who do not call themselves Indians.”

The Ortega clan is among those whose lineage has been called into question. Tribal members point to a notation in the 1925 census: “Agency physician reports that the Ortegas have Spanish blood and resent being classed as Indians.”

Robert “Ted” Ortega is vice chairman of the band. Ortega, 38, said his family’s status is being challenged by a faction seeking to remove as many as 90 of the 153 Indians enrolled in the tribe.

“A lot of it is greed,” said Ortega, asserting that the challenge to his family’s ancestry is without merit. “For them to say, ‘You don’t belong,’ I don’t understand it.”

One of the most contentious cases involves the Talaugon family.

In 1988, Joe Talaugon, then 58, submitted an application to the tribe. Like some Chumash descendants, he did not learn of his Indian heritage until he was an adult.

After rejecting the application, the band granted Talaugon’s appeal, making him a member in 1991. Shortly thereafter, his mother and his five siblings applied.

The tribe accepted Talaugon’s mother and two brothers, but denied admission to another brother and two sisters.

“It defies common sense,” said attorney Dennis G. Chappabitty, who represented the family. “When the same blood flows in the same family, why are some in and not others?”

One member, Bud Talaugon, said, “It’s very frustrating. We’ve gotten no answers at all.”

Some Chumash Indians say the disputes reflect the influence of the Armenta clan, which by some estimates makes up about a third of the Santa Ynez band.

Vincent Armenta is tribal chairman. His uncle, George, heads the enrollment committee. Two of George’s nieces serve on the four-member panel.

George Armenta, 79, said confidentiality rules prevented him from discussing current membership challenges. But speaking generally, he defended the tribe’s enrollment decisions as rigorous and fair.

He said that when he joined the committee in 1994, many records were missing or in poor condition. Today, the tribe uses computer software to track family histories and keeps enrollment documents under lock and key. “If you follow your rules, you can’t do anything wrong.”

Armenta said the committee has been studying whether to employ DNA testing, a prospect that has some members worried.

“Blood degrees on all reservations are artificial to some extent,” said John R. Johnson, a Santa Barbara anthropologist who specializes in Chumash history. “If tribes go back and redo blood assignments, it would be a real mess.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.