A plot both wide and thick

- Share via

ASTRIDE his horse, Benjamin Coates could gaze across 21,400 acres and see the sweep of his power reflected in nature. A riot of mesas and meadows laced with gurgling streams. Miles of chaparral and clusters of stately oaks. A mountain that Native Americans considered a deity. Herds of deer, golden eagles overhead, enough wildlife to stock a zoo. And not another soul in sight.

This was Xanadu and it belonged to Coates.

The Pennsylvania-born businessman collected property the way others accumulate Hummel figurines. He owned a Manhattan office building, a hunting estate in Scotland, a Swiss chalet, apartments in Paris, New York and Tokyo. But above all else, he prized Rancho Guejito, Southern California’s last undivided Mexican land grant.

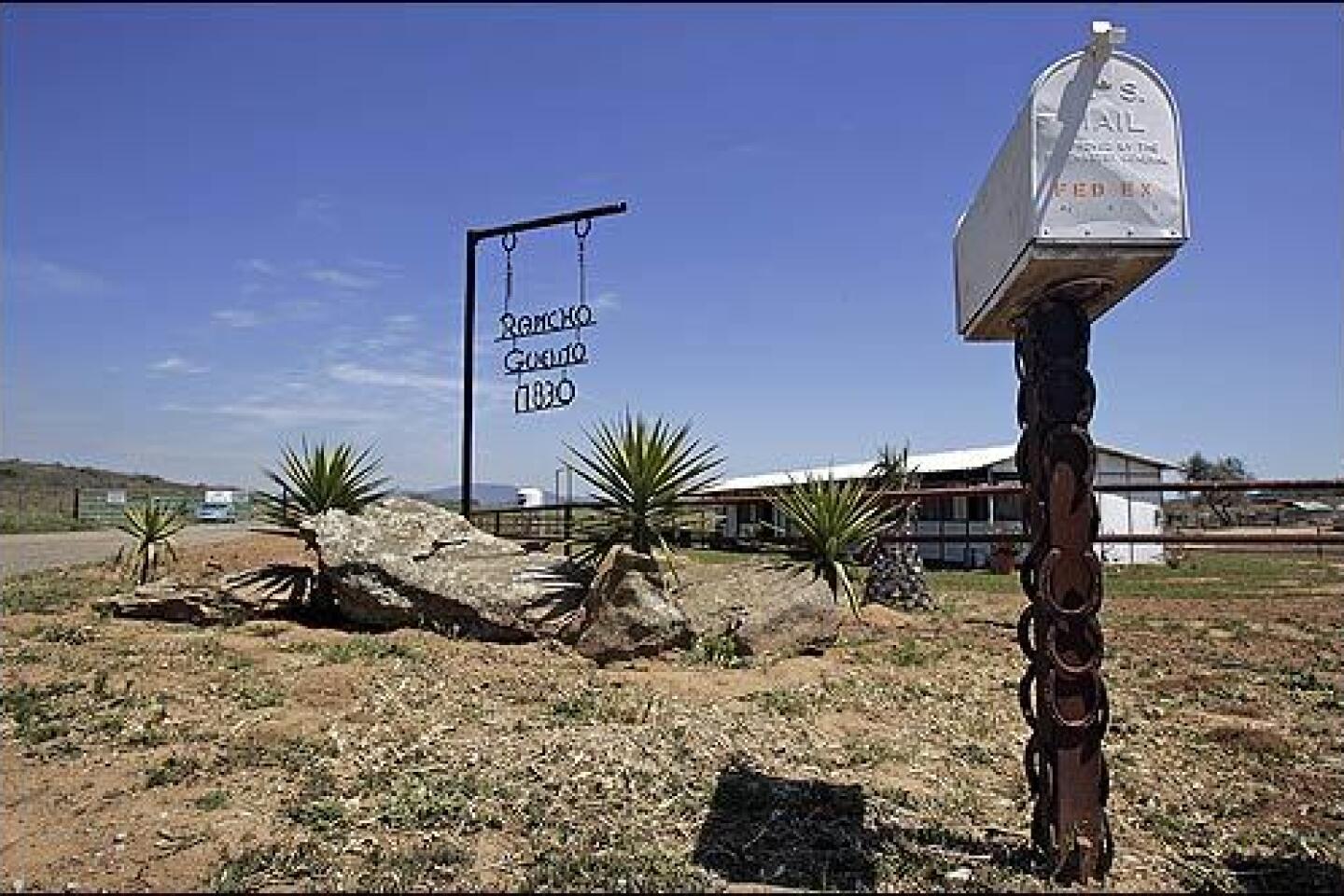

Most people have never heard of Rancho Guejito, in northern San Diego County. Few have seen it. Shielded from view by ridgelines, with only one road leading to a locked gate and a security guard, the ranch is a time capsule from 1845, when Mexico’s California governor awarded the core of it to San Diego’s customs inspector.

Since then, a series of wealthy men ran cattle and used Rancho Guejito (pronounced Weh-HEE-toh) as a private playground. Coates was the last. It was the jewel of a billion-dollar-plus fortune the 86-year-old aristocrat planned to pass down to generations of heirs with instructions that it never be developed.

“No American family lasts. In Europe they still do but the times are against families lasting out,” Coates wrote to an acquaintance. “I do not want my life’s work to be dispersed. It is organized to go on and I want it to go on.”

Then, in 2004, he died. Soon, neighbors in Valley Center, a once-rural enclave tilting toward suburbia, noticed surveyors around the land. An attorney for Coates’ daughter floated vague development ideas.

The mere suggestion that any part of Rancho Guejito could be paved over has mobilized environmentalists.

Bill Horn, a San Diego County supervisor and property rights advocate, is no environmentalist. But he feels betrayed. For years, he worked to keep government regulators off Coates’ back. Now, Horn believes the government needs to buy Rancho Guejito.

“This place is like a little Shangri-La that everyone forgot about,” he said.

Whether one of the most ecologically valuable swaths of private land in California remains that way is anything but certain.

At the center of the drama is Coates’ daughter, Theodate, a 60-year-old New York artist who controls her father’s empire. Some suspect the recent talk about development is part of a broader scheme to get around proposed county zoning changes and other government regulations that would undercut the ranch’s value. Then it could be sold to the state for preservation at a higher price.

Hank Rupp, the attorney who represented Benjamin Coates for two decades and now speaks for Theodate, denies that that’s the strategy — although he won’t shut the door on the possibility.

“Let me cut through the cat-and-mouse stuff and give it to you straight,” he said. “We’re absolutely not interested in selling it to the state in the foreseeable future.”

Rupp won’t say how far into the future he can see. Nor will he elaborate on the development proposals. But he has approached Escondido city officials to explore whether the ranch can be annexed to remove it from county oversight.

If Escondido won’t, maybe San Diego will, he says.

On another front is an acrimonious legal battle in which the great-grandson of legendary Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt contends that he, not Theodate, is the rightful manager of Coates’ estate.

Al Hill III says Coates, a longtime family friend, didn’t think his daughter or son was up to the job. Hill contends that Coates all but adopted him and was finalizing a deal that would have put him in control. The only problem: He didn’t get around to signing the papers.

Such public skirmishes would have angered Coates, an intensely private man accustomed to giving orders and getting what he wanted, a steely entrepreneur who relinquished his U.S. citizenship so he could move his holdings overseas and avoid taxes.

“When you went to see Mr. Coates, you listened and he talked,” said rancher Willie Tellam, who ran cattle on Rancho Guejito for decades. “That’s why we got along. He lived quite a life, and I heard the same stories over and over again.”

Tellam, 75, is among the few locals who got to know Coates, who would visit several times a year and survey his land on horseback wearing English riding clothes.

“Like a lot of rich guys, their word was the law,” Tellam said. “I think Mr. Coates thought he was going to live forever.”

*

RANCHO Guejito was off the beaten path even by the standards of early California. It was far from the traditional travel routes of the Mission era.

This isolation has engendered a mystique common to veiled places. It’s a mystique that has grown with California’s population and the division or disappearance of hundreds of Spanish and Mexican land grants.

Those lucky enough to get an invitation — or bold enough to trespass — say Rancho Guejito lives up to the legend.

“It was a very emotional journey for me that first time,” said Bob Lerner, a San Diego County historian who was a guest several times. “I felt like I was being transported back to when California was part of Mexico. Nothing had changed.”

A request to tour the ranch for this story was denied. Seen from the air, Rancho Guejito is a startling contrast to the jumble of housing tracts and commercial strips that inch closer with each year. That one man owned this much of Southern California — a spread five times the size of Griffith Park — is nearly unimaginable.

The 8,000-square-foot hacienda-style home Coates built is on a ridge at the ranch’s southern end. Its U-shaped courtyard and swimming pool overlook the property — a dozen miles long, 3 across.

A broad mesa stretches north flanked by two pine-studded valleys that converge in a vast meadow fed by Guejito Creek and its numerous tributaries. Cows munch grass that is 2 feet high in places. Everywhere are stands of Engelmann oaks. Over the lush hills are more mesas, valleys and creeks. A maze of rugged mountains anchors the ranch’s northern end.

The property’s catalog of riches include Indian archeological sites, bobcats, coyotes, wild turkeys, mountain lions, and 16 types of raptor.

In the early 1970s, the state nearly bought it all for use as a park. Coates, who already owned a Hemet ranch that once belonged to John Wayne, scooped it up for about $10 million.

Over the years, he fought attempts to take parts of it for a reservoir and an airport but rejected offers to sell it for preservation.

Land was in Coates’ blood. In the 1680s, his Quaker ancestors were among the settlers of Pennsylvania, established under the King of England’s royal charter.

Coates prospered in a variety of businesses — shipping, oil wildcatting and furniture among them. But land is what stirred his passion.

He sold a thoroughbred that won a major French race to buy a 23,000-acre spread in Scotland. Wanting to watch the America’s Cup yacht race off Newport, R.I., Coates is said to have bought a seaside estate — then sold it after the race. When he couldn’t find a suitable penthouse in Manhattan, he financed an apartment building on the Upper East Side and took the top for himself.

Coates, solidly built with a broad forehead and square jaw, was a man of the world. He was a decorated Navy pilot who hunted Nazi submarines in the Atlantic between Brazil and Africa. His friends were royalty — the Bismarcks of Germany and Japanese Prince Fumitaka Konoe, whom he met in college at Princeton.

With a passport from Belize, he moved between homes in Europe, the United States and Japan. For a time, he owned the world’s fourth-largest yacht and docked it in the French Riviera.

“As long as I had her I was king,” Coates wrote in a letter. “When I let her go, I was never king again.”

In 1960s, Coates began transferring his holdings to a complex web of foreign companies, many of them in Liberia. Rancho Guejito is managed from Colorado Springs, Colo., New Jersey and New York and is owned by a Netherlands Antilles company that, in turn, is owned by a trust in Liechtenstein.

But Coates wasn’t a nouveau riche jet-setter. Money was as natural as the rising sun. He was born with it, married into it (Nancy Coates inherited her own fortune) and made far more through entrepreneurship. Coates believed such wealth should be nurtured and passed on. A student of history, he also recognized money’s dark side.

“Almost in the entire history of the world great wealth has been highly associated with disaster, tragedy and unhappiness,” Coates wrote.

*

COATES possessed Old World sensibilities that shaped his views on issues from global politics to family affairs. He could be dismissive of women, those who know him said. He didn’t think much of most men either.

“There are very few men that I have great respect for now,” Coates wrote to Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger a few months before he died. “Greatness is a passing phenomenon . When I see you on the television, I am convinced you have the strength that we are so lacking now.”

The letter is similar to others Coates wrote late in life, rambling autobiographical narratives that depict a man of the past intent on controlling the future.

The Liechtenstein trust Coates created in 1986 was the vehicle to accomplish that. Coates named his son, Ben Jr. — listed as vice president of Coates Bros. Co. Inc. on the father’s letterhead — to become principal trustee upon his death. Theodate Coates isn’t mentioned in the document.

But something happened that changed Benjamin Coates’ mind. He had a falling out with his son — no one familiar with the details will say why.

“I just don’t think they saw things eye to eye on making a profit, on doing what you’re supposed to do, on working a job regularly,” said Matthew Dowling, an Oklahoma City attorney who once represented the younger Coates. “Things that a man would expect from his son.”

So Coates went looking for a man he could groom for the job.

Coates came to know the Hill family of Texas in the early 1960s after he got into the oil business and bought a home in the blueblood River Oaks neighborhood of Houston.

Al Hill married heiress Margaret Hunt, the first of H.L. Hunt’s 14 children from three families, two of which he kept secret for years. The Hunts and Hills were Texas royalty and embodied qualities Coates admired: generational wealth built by shrewd, self-reliant risk-takers.

Hill’s 36-year-old grandson, Al Hill III, is a Dallas investor and socialite who married a former Miss Georgia. Hill was 18 when he met Coates.

How the aging billionaire came to consider Hill worthy of managing his holdings — and passing this responsibility to Hill’s male heirs — is spelled out in Hill’s lawsuit against Theodate Coates, filed in a New York court. (A separate action was filed this week in a Liechtenstein court.)

“I believe it was the second time I met Al III that I realized the marvelous presence the boy presented,” Coates wrote to a lawyer representing the Hill family.

Documents cited in the suit show that Coates told business advisors and attorneys to create a company overseeing a new Cayman Islands trust that Hill would be paid handsomely to manage. Theodate was to play a secondary role, the documents show.

Hill’s role, Coates wrote, would be “overlooking what women cannot necessarily do properly — lawyers, employees, etc. Nobody would have ever given me the chance that I am suggesting for Al III.”

Hill says he and Coates made an oral agreement for Hill to begin managing the Liechtenstein trust and oversee its transfer to the Caribbean. Coates told his attorney to provide “strong incentives” to prevent his children from challenging the new trust, according to a memo between the two.

Hill wants the courts to hand him the keys to Coates’ empire and assess monetary damages against Theodate.

“He’s rolling over in his grave right now over how it’s being handled,” Hill said. “He became like a grandfather to me. And I became like a son to him.”

Hill was a pallbearer at Coates’ funeral. Ben Coates Jr. didn’t attend.

Attempts to reach the younger Coates, 57, were unsuccessful. He carried driver’s licenses from Brazil and the Bahamas when he was arrested in 2002 after a confrontation at a Colorado Springs office from which Rancho Guejito’s accounting is done.

Witnesses reported that Coates burst in screaming about forest fires, suing President Bush and how the Irish Republican Army had killed his wife. He had to be subdued by police. Eventually, charges of disorderly conduct and resisting arrest were dismissed.

Rupp, the Coates family attorney, won’t discuss the younger Coates. And Theodate Coates doesn’t grant interviews, he said.

Rupp is the public face of Rancho Guejito. A former Riverside County prosecutor, he seems to enjoy upsetting adversaries. Rupp left conservationists aghast when he recently proclaimed, “There isn’t enough money in the state treasury to buy Rancho Guejito.”

Rupp is an indoorsman who finds the ranch’s wildness unnerving. “When you go out there, you want to strap on a sidearm,” he said. “I don’t get out of my car. Things sneak up on you there . There’s a rumor that there’s a jaguar.”

Equally predatory, Rupp says, is Hill’s attempt to wrest control of Rancho Guejito and the rest of Benjamin Coates’ holdings.

Hill says he is simply trying to fulfill the wishes of his mentor.

“You’ve got to be kidding!” Rupp said, erupting into laughter and slapping his hand on a table.

Lawyers for Theodate Coates argue that even if her father had signed the new trust documents, it wouldn’t have been legal because the original was to last 100 years and is irrevocable. Hill’s purported oral agreement with Coates is unenforceable in New York, they argue, and filing a claim in Liechtenstein is irrelevant because, well, this isn’t Liechtenstein.

“Mr. Coates only had trust in his daughter. He had trust in Theodate’s business acumen, integrity and abilities. That’s the way he left it — intentionally,” Rupp said. “He basically flirted with the idea of other business [arrangements] but never was serious about any of them.”

The detailed memos and draft documents indicate far more than flirtation. Coates, who spent his final years working through the complicated personal and legal issues of his legacy, may have simply run out of time.

“My father’s inability to finalize his thinking and put pen to paper,” Theodate Coates wrote in a letter to Hill’s father before the dispute wound up in court, “has made things more complicated for us than we all would wish.”

And his desire to keep Rancho Guejito from becoming “mixed up with money,” as he wrote, now seems as fanciful as this unique expanse of Old California that few have ever seen.

*

mike.anton@latimes.com

*On latimes.com

Aerial view

For a flyover view of Rancho Guejito, go to latimes.com/ranchoTo see recent Column One articles, visit latimes.com/columnone.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.