Quake triggered collapse of ancient Peru society

- Share via

Archaeologists generally argue that the Maya civilization and others in South and Central America perished as a result of intense warfare or prodigal consumption of resources.

But for one early society, the cause was more elemental -- earth, wind and water.

The residents of the Supe Valley on the central coast of Peru thrived for more than 2,000 years, building the first massive pyramids on the continent, fishing, farming and extending their hegemony for more than 60 miles along the coast and through five river valleys.

Then they disappeared over the course of a few generations; researchers said Monday that they now know why. About 3,800 years ago, a massive earthquake struck the region, toppling buildings and, more important, loosening soil upriver.

Massive rainfall triggered by El Nino weather patterns washed the sediment into bays, destroying the fishing grounds. Constant winds then blew a steady rain of sand ashore, burying farmlands and rendering population centers virtually uninhabitable.

“These people did quite well for 2,000 years, they were quite successful, then ‘Boom!’ they just got the props knocked out from under them,” said archaeologist Michael E. Moseley of the University of Florida, one of the authors of the paper appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

It took 200 years for the population to begin to rebound as the people developed more sophisticated ways to respond to the climatic alteration.

The story of the Supe Valley shows that some catastrophes are not preventable, said archaeologist Thomas D. Dillehay of Vanderbilt University, who was not involved in the research.

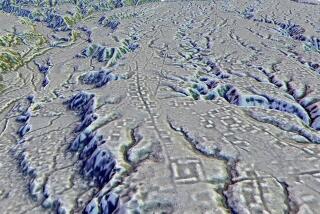

The Supe Valley, about 120 miles north of Lima, lies in Peru’s coastal desert. When the first humans -- a group that has no formal name but is often called the Supe society -- occupied the region about 5,800 years ago, the bays along the coastline provided an abundant source of fish and shellfish. Fresh water carried by rivers from the inland mountains provided water for drinking and irrigation.

The early residents did not make pottery or weave cloth, but they grew cotton for fishing nets, as well as a variety of vegetables and fruits. They built large stone pyramids thousands of years before the Maya.

The best known of these was 100-foot-tall Piramide Mayor at Caral, about 12 miles inland. Walled courts, rooms and corridors covered the flat summit.

Caral is one of seven sites in the region being excavated by Peruvian archaeologist Ruth Shady Solis, director of the Caral-Supe Special Archaeological Project and a co-author of the report.

The region has been subject to many earthquakes over the millenniums because it is where a tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean, the Nazca Plate, crashes under the South American Plate. But evidence from Caral and other sites shows that an especially strong temblor struck the region about 3,800 years ago. Moseley estimates that it was at least magnitude 8 or that there were two or more quakes, each greater than magnitude 7.2.

The Caral pyramid was severely damaged and the structures atop it were devastated. The evidence is unusually well preserved because the structures were not rebuilt. Strata in the soil and damage to other pyramids in the region confirm the severity of the earthquake.

The quake also loosened soil on the hillsides upriver from Caral and other communities, and dumped it into the rivers. When El Ninos -- which had been quiescent for centuries before making a coincidental return after the quake -- brought heavy rainfall to the region, the sediment washed into the bay, where currents formed it into a 60-mile-long ridge in the ocean that is now known as Medio Mundo.

The ridge sealed off the formerly rich coastal bays, which rapidly filled with sand, eliminating one source of food for the Supe society. As the bay filled, strong, near-constant onshore winds blew the sand inland, burying the farmland.

The environmental catastrophe “had an astonishing impact on the landscape over quite a wide area,” said archaeologist James B. Richardson III of the University of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the research.

The lesson of the tale is that, in piecing together historical events, “we’ve got to pay attention to what is happening across all parts of the landscape,” said archaeologist Daniel H. Sandweiss of the University of Maine, another co-author.

This was a complex chain of events “that took decades to begin to affect people’s livelihood,” he said. “By not being able to look decades ahead, they were not able to cope with it” and their society collapsed.

Their organization collapsed and their faith in their religious system probably faltered, he said. “They stopped building monuments, and they never regained the prominence they had early on.”

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.