Lincoln’s slavery tactic

- Share via

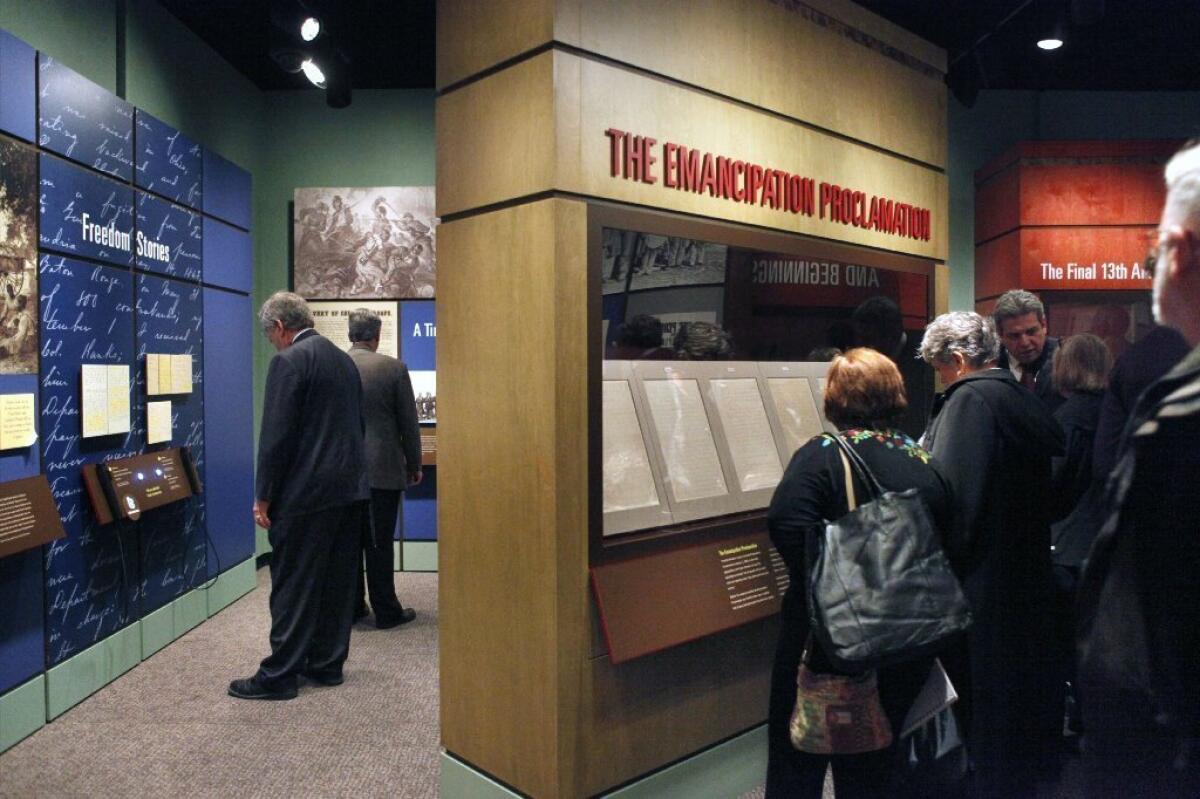

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln 150 years ago this week, has often been criticized by blacks, by radicals and also by mainstream historians who doubt its significance as a turning point in the Civil War and in American history.

The skeptics range from conservatives in Lincoln’s time, to Howard Zinn and Gore Vidal more recently, and include Richard Hofstadter, who wrote in his classic 1948 book “The American Political Tradition” that the Emancipation Proclamation “had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading.” The critics argue that the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t actually free any slaves. Lincoln “freed” the slaves, the argument goes, only where he had no power — inside the Confederacy.

As the proclamation put it, “slaves are, and henceforward shall be free,” but only “in the States and parts of States wherein the people … are this day in rebellion against the United States.” In the slave states where he did have power — the border states that remained in the Union — Lincoln’s Proclamation left slavery intact.

The skeptics have a point, but they miss the larger context and historical significance of Lincoln’s actions. It’s true that the proclamation applied only to the Confederacy, where of course slavery remained protected by the Confederate government and army. It specifically exempted from emancipation slaves in states that remained loyal to the Union, as well as several areas of the slave South occupied by the Union Army, which meant that nearly 4 million remained in slavery even after Jan. 1, 1863.

But Lincoln had sound reasons for doing it the way he did.

Slavery existed because of state laws, and the president had no power to declare state laws invalid. The Supreme Court could declare a state law unconstitutional, but nothing in the Constitution as it existed in 1863 made slavery unconstitutional. The president instead based his legal argument for abolishing slavery on the Constitution’s grant of war powers to the president. Claiming that slavery was enabling the rebels of the South to carry out their war, he maintained that abolition was “warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity” to save the government.

“The Emancipation Proclamation was as much a political as a military document,” Eric Foner notes in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Fiery Trial: Lincoln and American Slavery.” Before the war, Lincoln and many others had argued that slavery should be ended by the states, gradually, and that slaveholders should be compensated. Foner emphasizes the point made by the abolitionist Wendell Phillips that the proclamation “did not make emancipation a punishment for individual rebels, but treated slavery as ‘a system’ that must be abolished.”

A key part of the Emancipation Proclamation was its invitation to freed slaves and other African American men to enlist in the Union Army. Lincoln’s proclamation thus “addressed slaves directly,” Foner observes, “not as the property of the country’s enemies but as persons with wills of their own whose actions might help win the Civil War.”

Arming former slaves was truly a revolutionary step, as controversial as emancipation itself. In Lincoln’s view, as he wrote in a letter to Andrew Johnson, “the mere sight of fifty thousand armed and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once.” Indeed more than 180,000 black men served in the Union Army, the great majority of them emancipated slaves. More than one-fifth of the nation’s adult male black population younger than 45 fought for the Union, about 10% of the entire Union Army. Lincoln went so far as to declare the re-enslavement of black soldiers “a relapse into barbarism and a crime against the civilization of the age.”

It would take the 13th Amendment to enshrine the end of slavery in the Constitution, but with the election of 1864, Republicans achieved a super-majority in the House that made passage of the Amendment more or less inevitable. The Emancipation Proclamation did not literally free all slaves. But by committing the president, and the nation, to emancipation, and by making the Union Army an army of liberation, it made the end of slavery in the U.S. only a matter of time — and military victory.

Jon Wiener is professor of history at UC Irvine and the author, most recently, of “How We Forgot the Cold War: A Historical Journey Across America.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.