Sweat-free labels to change the garment trade [Blowback]

- Share via

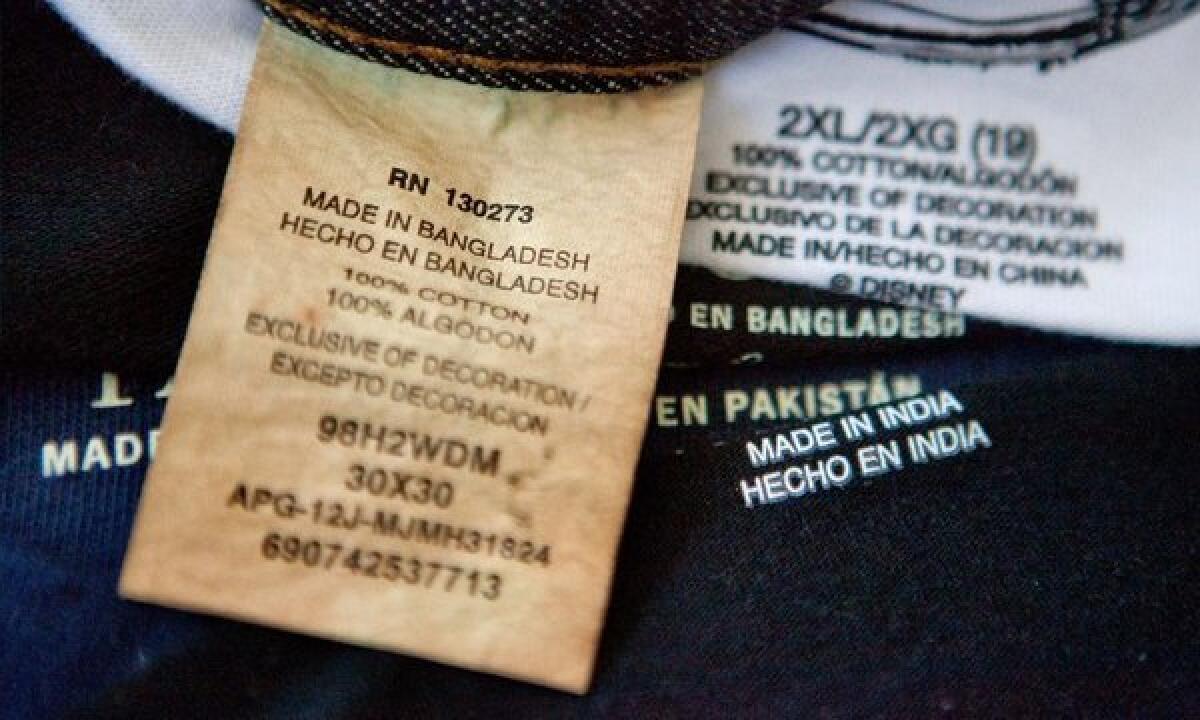

In a May 7 Op-Ed article, Richard Greenwald and Michael Hirsch exhort consumers to support the workers who make our clothes rather than the global apparel industry that exploits them with low wages and unsafe working conditions. Yet exactly how we should do this remains unclear. We need to be more specific about our moral responsibility so that the “labels we wear not be stitched in blood.”

Should we be faulted for not buying clothes with the “Made in USA” label, for example? Aside from the issue of whether a boycott is effective in improving conditions under global free trade, finding clothes with the label can be difficult. Moreover, even if a garment advertises its American origins, it might still have been produced under abysmal conditions.

Turns out that something as simple as “Made in USA” has loopholes.

First, sweatshops do exist in the United States, especially in large cities such as New York or Los Angeles; they also appear close to the nation’s southern border. These gray-market businesses are able to exploit undocumented or uneducated workers through piecework or home-work arrangements.

Second, the “Made in USA” assurance doesn’t necessarily guarantee the clothes were actually made within the 50 states. The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, for example, entered into a political union with the United States that exempted it from federal immigration and minimum-wage laws. Workers were imported from other parts of Asia, paid poorly (if at all) and kept in conditions akin to involuntary servitude. But the clothes could boast the “Made in USA” label, a privilege that was especially important before global free-trade agreements.

Finally, clothes with a “Made in the USA” label may in fact be made in U.S. prisons. The 13th Amendment’s ban on slavery and involuntary servitude exempts work done as “punishment for a crime.” Prison industries, touted as factories with fences, manufacture a wide range of apparel and specialty clothing for government use. They also partner with private corporations to supply clothes for sale to the general public.

But while a “Made in USA” label may be no guarantee of sweat-free (and child-free) labor, perhaps a mandatory label of another sort could be a solution. What if each piece of apparel was required to bear a label that it was -- or was not -- sweat-free? Mandating prominent sweat-free labels is not on the legislative or regulatory agenda at the moment, but it would solve a long-standing problem.

As the U.S. Supreme Court noted nearly a century ago when it struck down a federal law limiting child labor, there is nothing inherently evil in the textiles produced by children. Though Americans have abandoned such logic in our reconsideration of laissez faire, the rationale still applies in the realm of global free trade. A required label would be a proclamation of a garment’s evil.

Of course, businesses would vigorously oppose any such requirement, just as the Southern cotton manufacturers of the early 20th century challenged child labor laws. Contemporary garment corporations would say forcing them to include this information on their products would violate their free-speech rights. Although commercial speech is traditionally less highly valued than political speech, this argument has achieved varying levels of success in assorted circumstances. Tastefully printed warnings, but not graphic images, adorn cigarette packs; required disclosures for items containing “conflict minerals” are being litigated; and various proposals to label genetically modified foods are in the works.

Certainly, the law is in flux. But just as it once seemed impossible that the government could interfere with the rights of companies to contract for labor at any price, it may seem unthinkable now for the government to revoke the right of companies to be ignorant of their supply chains. But just as child labor laws changed, labeling laws should do likewise.

In our nation’s infancy, some patriots criticized George Washington for dressing in the “manufactures of foreign nations” despite his proclaimed homespun economic policies. Perhaps everyone who looked at the first president could quickly discern the origin and cost of his clothes. Today, we can barely determine the provenance of what we ourselves wear.

So before we tell consumers to do their part, they actually need the ability to do so.

ALSO:

Vin Scully is the true voice of Los Angeles

Outraged over the IRS snooping scandal? Readers aren’t

Ruthann Robson is a professor at the City University of New York School of Law. Her forthcoming book, “Dressing Unconstitutionally,” considers legal issues surrounding clothes, including their production.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.