Editorial: Vermont’s newest export is bad GMO policy

- Share via

Californians smartly rejected a ballot initiative in 2012 that would have required warning labels on groceries containing genetically altered organisms. It was bad policy based on nothing but conjecture. There’s no evidence that eating GMO-laden foods is harmful to humans.

But GMO warning labels may be forced on food sold in this state nonetheless. If so, we can thank a tiny state with a population smaller than San Francisco. In 2014, Vermont lawmakers gave in to fear mongers pushing junk science and adopted a GMO labeling bill that took effect Friday. That’s too bad for Vermonters, who are just starting to realize that the new law will mean, at least for the short term, the withdrawal of thousands of products from their grocery stores. But it may prove problematic for consumers in the rest of the country too.

It is wrong to let the baseless fears of certain consumers dictate national food policy. A warning label, however mild, connotes danger.

That’s because the U.S. Senate may very well pass a national GMO labeling bill this week to appease the freaked-out food industry, which has legitimate concerns about the cost and confusion of rejiggering its supply chain. A compromise worked out by Sens. Pat Roberts (R-Kansas) and Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.), leaders of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, is a watered-down version of Vermont’s mandate that would preempt state labeling laws, including those passed in Vermont, Connecticut and Maine.

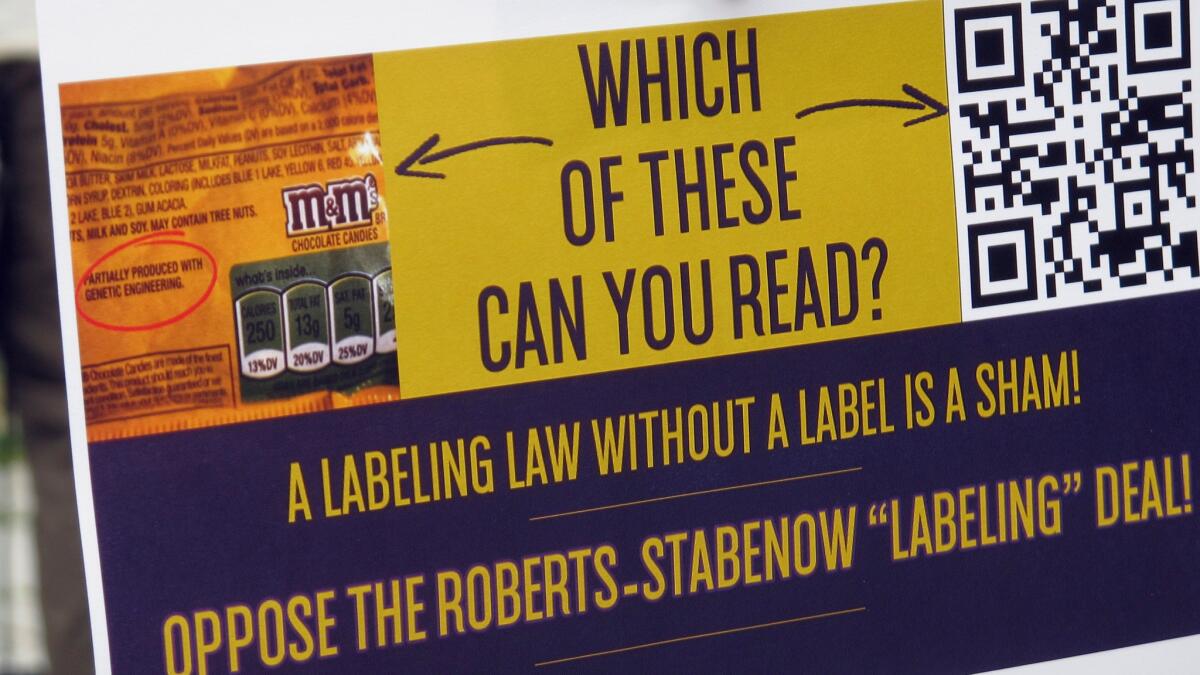

The Roberts-Stabenow bill would require food labels to disclose the presence of GMOs but would allow for different ways of doing it. Manufacturers could meet the requirements with text, a symbol or a QR code linking to a website with more information. The bill would also exempt products that consist mostly of meat or are made by very small manufacturers.

GMO label supporters, misguided though they are, ought to be pleased they’ve managed to parlay a small score in Vermont into a national victory. But some are complaining about what they’ve dubbed the Deny Americans the Right to Know (DARK) Act because it isn’t as strict as Vermont’s law.

We agree that this bill is troubling, but for a different reason. It is wrong to let the baseless fears of certain consumers dictate national food policy. A warning label, however mild, connotes danger, and that unfairly stigmatizes approximately 70% of the packaged food in our grocery stores.

For all the consternation about “frankenfood,” there is no scientific evidence that foods with GMOs are dangerous to humans — and scientists have been looking closely for that evidence. In May the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine concluded in a sweeping study that GMO crops should be considered just as safe as the non-GMO versions.

If food manufactures want to tout their GMO-free status, that’s fine. But the government should not be in position of forcing them to do so in the absence of any verified threat to human health.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.