Op-Ed: Will an optimist or a pessimist win in 2016?

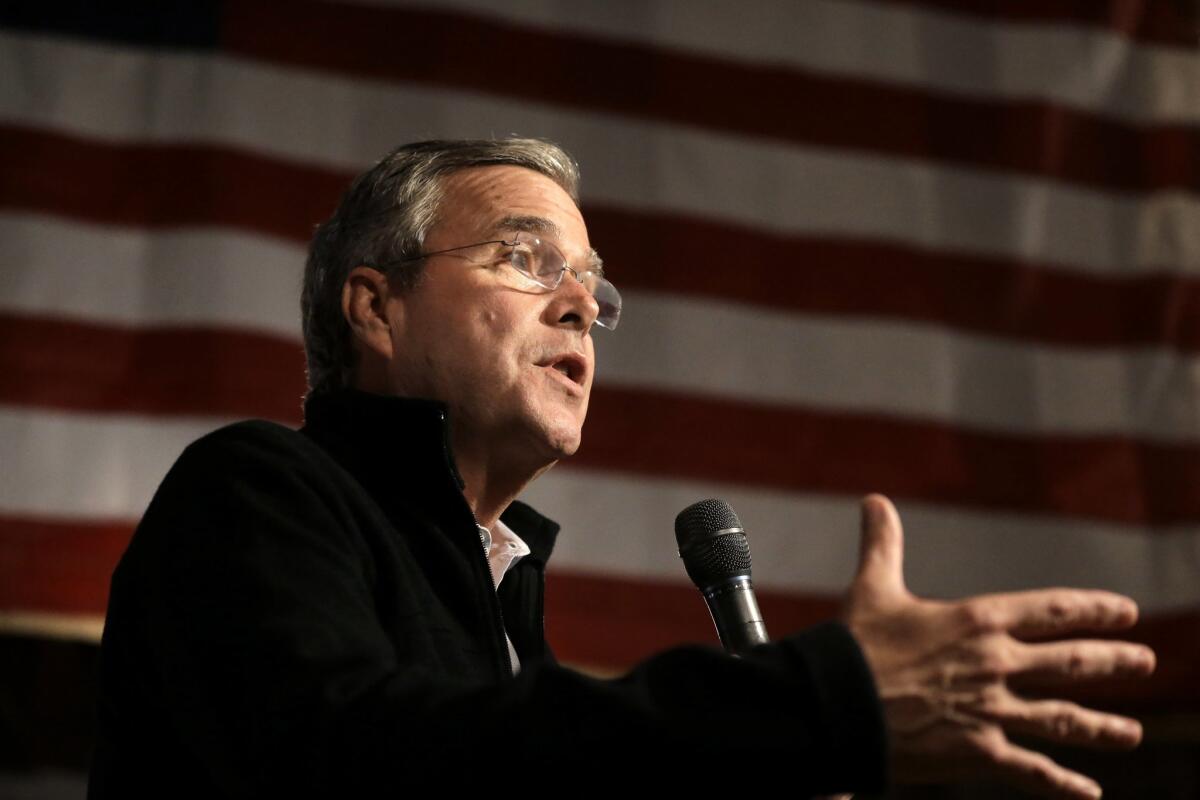

Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush addresses an audience at a campaign event on Nov. 3. Bush recently said he believes “we’re on the verge of the greatest time to be alive.”

- Share via

This campaign season, voters have a choice between two starkly different rhetorical styles.

“Americans will die.” “America is adrift. Something is clearly wrong.” “America is a hellhole, and we’re going down fast.”

These are not the chants of America’s enemies abroad but the pronouncements of Ted Cruz, Rand Paul and Donald Trump.

Not everyone running for the country’s top job is equally dour. Consider John Kasich’s rhetorical question in a campaign ad: “Why don’t we count our blessings for having been born in the United States of America?” Or Hillary Rodham Clinton’s assertion that “America can lead the world in the 21st century.” Or Jeb Bush’s “We’re on the verge of the greatest time to be alive.”

Will an optimist or a pessimist carry the day?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, candidates whose speeches were sunnier and less likely to dwell on negatives were the winners in 18 out of the 22 elections.

Studies show that happier and more positive people are better liked, more sought out as friends and regarded as more energetic, resilient and creative. Optimistic leaders are perceived to be more effective, and happier people are even judged to be more likely to go to heaven.

This research, conducted with a variety of participants, from undergraduates to CEOs, is certainly suggestive. But wouldn’t it be more telling if psychological scientists examined the positivity of presidential candidates and related it to election outcomes? As luck would have it, two researchers from the University of Pennsylvania already have.

In a classic study, Harold Zullow and Martin Seligman analyzed the party nomination acceptance speeches of presidential candidates from 22 elections, from the turn of the century (McKinley-Bryan) to 1984 (Reagan-Mondale). Widely covered by media (and televised since 1948), the Democratic and Republican convention speeches are highly informative vis-a-vis the candidate’s perspective on the state of the nation.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, candidates whose speeches were sunnier and less likely to dwell on negatives were the winners in 18 out of the 22 elections. Furthermore, the more positive the candidate was relative to his opponent — for example, projecting optimism that America’s problems were temporary and that he was the one to set things right — the wider his victory margin. (On a side note, Zullow and Seligman found that the more positive the candidate, the more active he was on the trail, making more frequent stump speeches.)

In the last election studied by Zullow and Seligman, Ronald Reagan — he of the campaign commercial that started with “It’s morning again in America” — trounced the more ruminative Walter Mondale in a landslide.

More recently, we have Bill Clinton calling for building a “bridge to the 21st century” at the 1996 convention, George W. Bush’s “Yes, America Can!” campaign slogan and Barack Obama’s ubiquitous “Yes We Can!” posters. In the last 30 years, the more positive candidate appears to have triumphed most (and perhaps all) of the time.

But what if conditions are truly bad? Let’s say the economy is tanking, violence is rising and an overwhelming majority thinks the political system is broken. Are voters any more likely to listen to pessimism? Maybe so.

Remember, there were four exceptions to Zullow and Seligman’s findings — four elections in which the more pessimistic candidate won. One was the Nixon-Humphrey contest, in which Richard Nixon was found to be only slightly more negative than Hubert Humphrey. The other three were the reelections of Franklin D. Roosevelt, from 1936 to 1944, which took place during the crises of the Depression and World War II. Perhaps FDR was a special candidate. Or perhaps when things are objectively miserable, delivering an optimistic message makes a candidate seem out of touch at best, and in denial or ignorant at worst. In such cases, realistic pessimism beats quixotic optimism.

What we don’t know is what objective misery entails. How bad is so bad that Americans prefer doom-and-gloom to cheerfulness?

Speechwriters trying to craft winning turns of phrase for their candidates should keep that unknown in mind, and also note that positive politics does not necessarily entail the Pollyannaish belief that we live in the best of all possible worlds (per Voltaire’s “Candide”). In the words of early 20th century Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci, the key may be to embody “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” — that is, to present oneself as an idealistic realist (as Clinton has) or to balance calls for change or even revolution (per Bernie Sanders) with sober acknowledgment of our nation’s problems.

Sonja Lyubomirsky is a professor of psychology at UC Riverside and the author of “The How of Happiness.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.