Op-Ed: A Supreme Court case could give the poor a better chance to escape the death penalty

- Share via

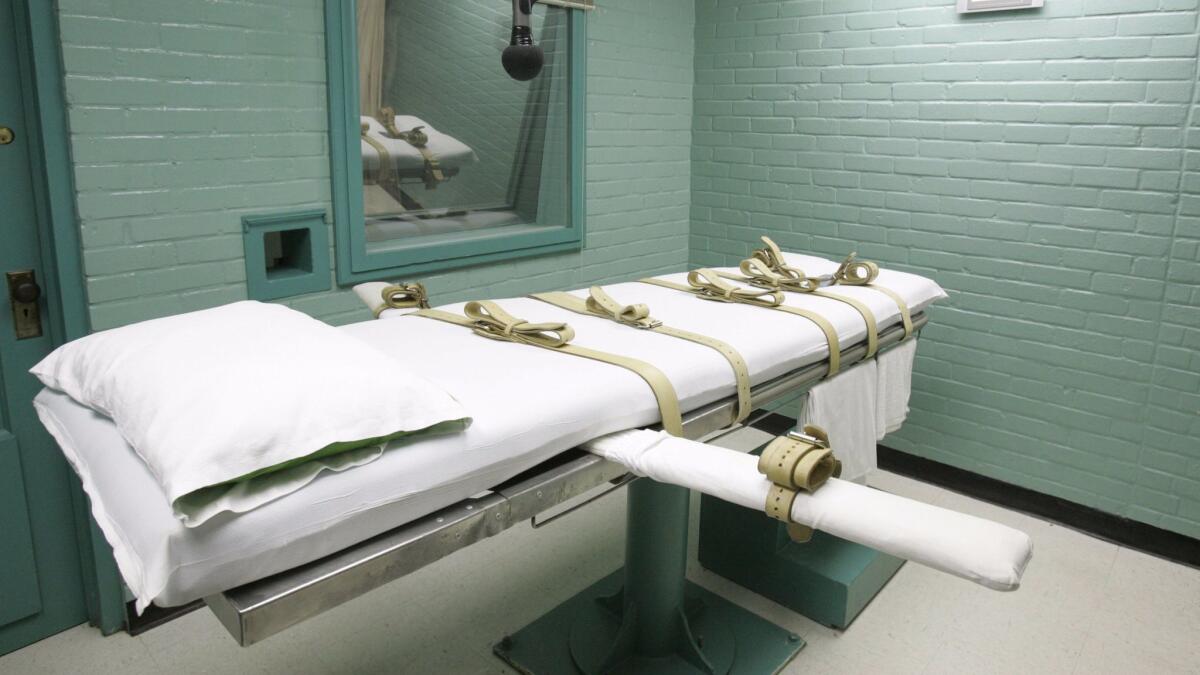

No one should face execution because they’re too poor to put on a defense. That’s the principle the Supreme Court will consider when it hears Ayestas vs. Davis on Monday.

In states with a death penalty, after a jury convicts a defendant of first degree murder, the jury hears evidence and decides whether to recommend a death sentence. The jury is required to consider the aggravating and the mitigating factors in coming to its conclusion.

Carlos Ayestas was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in Houston in 1997. His court-appointed trial lawyers performed virtually no background or mental health investigation before the penalty phase of his trial. Instead of presenting days’ or weeks’ worth of evidence explaining why their client should not be sentenced to death, Ayestas’ lawyers spoke for two minutes about the progress Ayestas had made in prison language classes.

There was much more to tell. Evidence suggests that Ayestas has suffered multiple head traumas, has a history of substance abuse and shows signs of mental illness. He has received one diagnosis of schizophrenia by a jailhouse medical professional, but he has never been seen by an independent expert. Each of these avenues of investigation was capable of producing mitigating evidence that might have prompted a jury to refuse a capital sentence.

No one should face execution because they’re too poor to put on a defense.

The Supreme Court has held that when attorneys fail to investigate possible mitigating evidence for the penalty phase of a trial, it constitutes “ineffective assistance of counsel” and is a basis for overturning a conviction or a sentence. Nonetheless, after Ayestas was sentenced to death, his case was brought to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals without success. Then new lawyers for Ayestas filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. district court. This federal court can grant the petition and order a new proceeding if it finds that a defendant’s constitutional rights have been violated.

To support the habeas corpus petition, Ayestas’ lawyers requested a court-funded investigator for their indigent client. In almost every federal court, such investigations are routinely authorized. But Ayestas’ request was denied, and when the denial was appealed to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the judges said Ayestas had to show what an investigation would uncover before it would approve funding for an investigation. This type of circular logic is indefensible and at odds with basic norms about the right to legal representation. A poor defendant should not be forced to prove what an investigation will uncover in order to undertake it.

Ayestas’ federal appeals were doomed because of an accident of geography. The courts in Texas are historically outliers when it comes to ensuring basic legal representation in death penalty cases. Where most federal courts appoint experts and investigators if they’re “reasonably necessary,” the 5th Circuit uses a much stricter standard. And when Ayestas’ case was taken up, the federal public defenders office in Texas didn’t have a Capital Habeas Unit — a group of attorneys, including mitigation specialists, that concentrate on death-sentence appeals. If a CHU had been assigned to his case (or if he’d been able to finance his representation), the basic investigation Ayestas requested would have been done as a matter of course. (The Texas courts have since established a CHU.)

In any other area of the country, the investigation Ayestas deserved almost certainly would have been granted. The Supreme Court now has an opportunity to ensure that everyone who faces the death penalty, no matter where they are in the U.S., will have the chance to uncover the information that might make a difference to a jury. No one should be put to death just because he or she is too poor to conduct an investigation.

Erwin Chemerinsky is dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.