Op-Ed: Thomas Jefferson helped define Americanism as the pursuit of happiness. But what does that mean?

- Share via

The beauty of all self-evident truths is that, by definition, we do not need to explain why they are true. Our annual celebrations of American independence fit neatly into this mental zone of confident presumptions. To the extent that we think about it at all, the Fourth of July is the time for summer vacation schedules to start, fireworks to appear at dusk and patriotic rhetoric to evaporate amid the airbursts.

It therefore might seem almost rude to suggest that we spend a few minutes asking ourselves what we are celebrating. The succinct answer is that we are honoring the 242nd anniversary of America’s birth as the first nation-sized republic in the modern world.

The values on which our republic was founded were proclaimed in 36 words that, over the years, have achieved iconic status as the American Creed. Here they are:

We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.

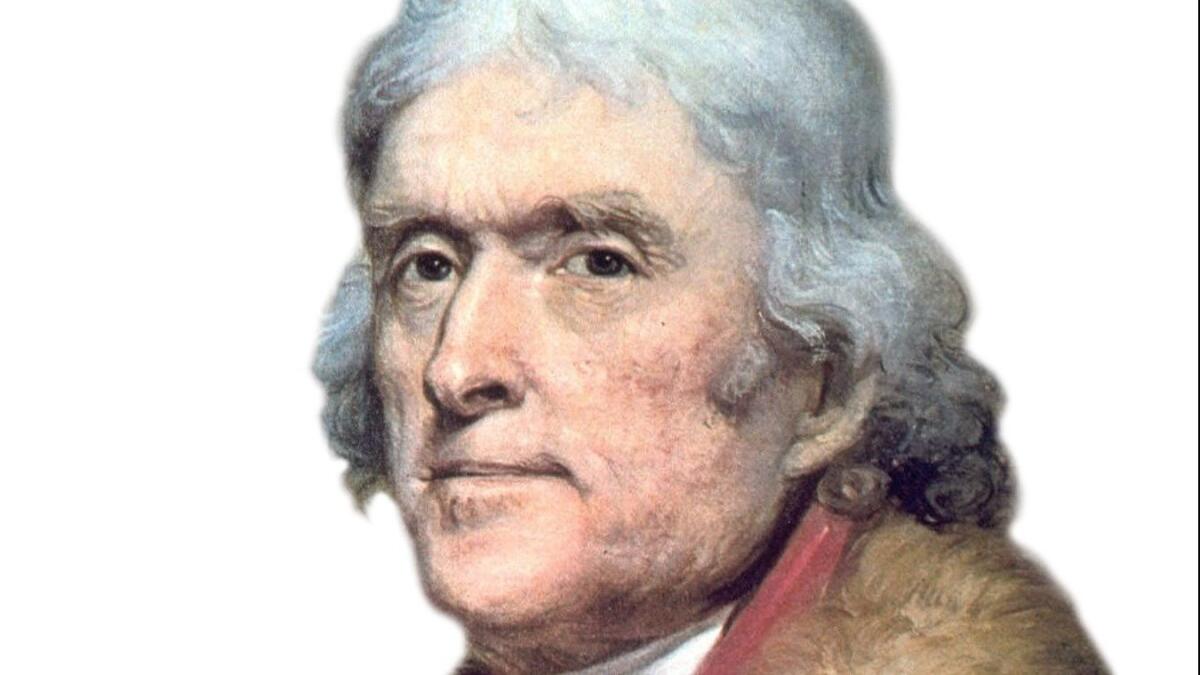

Thomas Jefferson wrote these words sometime in mid-June 1776 in his Philadelphia apartment at 7th and Market streets on a portable desk with a quill pen.

Does the decline of the middle class mean that our collective happiness as a people is at risk?

Historians have parsed their meaning in countless books over the ensuing two centuries: searching for their sources in the French Enlightenment or Scottish Enlightenment; questioning their utopian implications; criticizing their inherently elusive claims to visionary values that float above the world like verbal clouds; noticing that the portable desk on which they were composed was built by a former slave and that the author of those words was a dedicated racist.

But in the end, all such critics have found themselves shouting into the wind. For Jefferson’s words have levitated out of the historical context in which they were written to become the expansive mandate for the liberal tradition in modern America.

When the feminist movement was born at Seneca Falls in 1848, the manifesto began with the claim that “all men and women are created equal.” When Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address in 1863, he cited Jefferson’s words — “the proposition that all men are created equal,” to make the Civil War a fight to end slavery. When Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I have a dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, he announced that he was collecting on a “promissory note” written by Jefferson. Beyond our shores, the Vietnamese constitution, written by Ho Chi Minh, begins “We hold these truths to be self evident.”

In the mid-summer of 2018, during the increasingly divisive presidency of Donald Trump, do we still believe these words? Do we believe any truths are self-evident? Instead of spending our holiday on the Fourth contemplating the likely destination of LeBron James or the latest Kardashian rumor, let me propose that we discuss those questions.

The conversation might begin with a more specific focus: What did that hallowed phrase “pursuit of happiness” mean to Jefferson, and what does it mean to us?

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

Jefferson borrowed the words from George Mason, who had used the phrase in the preface to his draft of the Virginia Constitution a few weeks earlier. In the original trinity proclaimed by John Locke in his Second Treatise on Government, “life, liberty, and property” were the enshrined rights. By replacing “property” with Mason’s “pursuit of happiness,” Jefferson was making an implicit anti-slavery statement, depriving slave-owners of the claim that owning slaves — property — was a natural right protected in the founding document.

The Civil War removed slavery from the national agenda, leaving “pursuit of happiness” to float free and become a vague version of the American promise that meant pretty much what anyone wished it to mean.

Do we believe that Jefferson’s felicitous phrase now, in 2018, has economic implications? Does the self-evident right to pursue happiness entail the right to a living wage? Or affordable healthcare? Does the decline of the middle class mean that our collective happiness as a people is at risk? Do Jefferson’s magic words still possess the power to provoke some intellectual fireworks?

Joseph J. Ellis is the author of “Revolutionary Summer” and “Founding Brothers.” His latest book, “American Dialogue: The Founders and Us,” will be published this fall.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.