Opinion: How Abraham Lincoln’s last breaths may have saved others

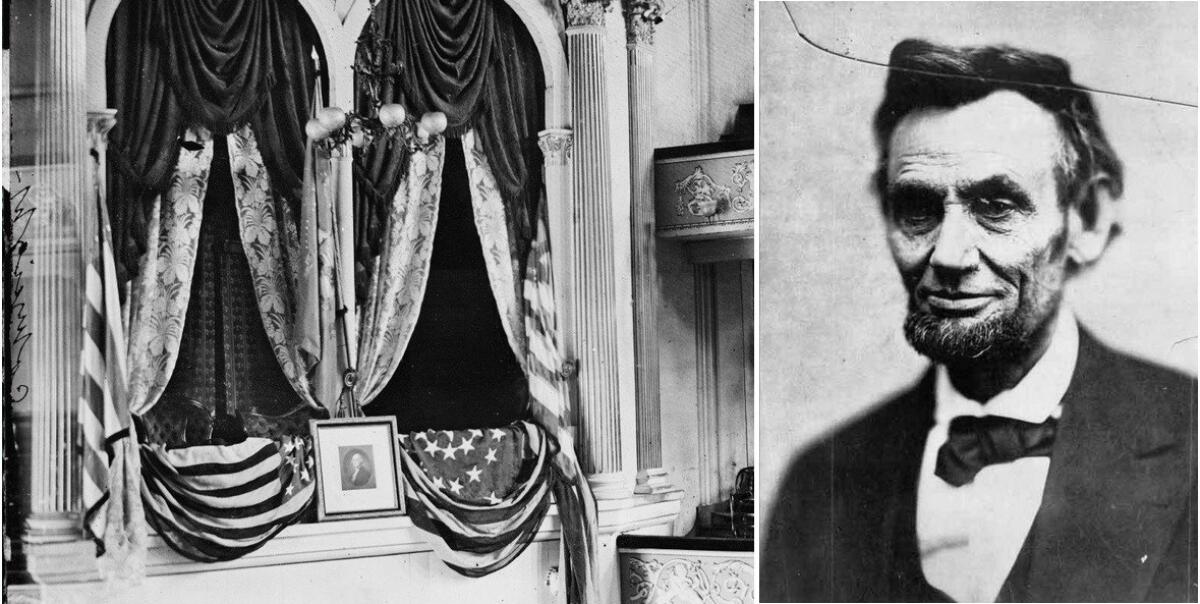

At left, the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., the day after Lincoln was shot there by John Wilkes Booth. At right, an 1865 photo of Lincoln believed to be the last taken of him.

- Share via

Abraham Lincoln drew his last mortal breath at 7:22 a.m. on Saturday, April 15, 1865 – 150 years ago.

Had it not been for Dr. Charles Leale, that last breath might have come nine hours earlier, as Lincoln lay in the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre with an assassin’s bullet in his brain.

Leale was very young, 23 and just out of medical school, when he bought a last-minute ticket to Ford’s Theatre. He wanted another glimpse of the president, whom he’d seen delivering a speech three days before, standing at a window above the door to the White House.

Aizita Magaña, a public health official at L.A. County’s public health department, ran across Leale as she researched a book about breathing (she once nearly drowned). She first recounted her research in Frontiers, the Huntington Library’s magazine.

As Magaña told me, Leale hurried to the presidential box and asked for permission to treat Lincoln. As blood clotted over Lincoln’s wound, Leale kept removing the clot, to relieve pressure on Lincoln’s brain. He accompanied Lincoln across the street to a boarding house and was with him through the night and at his death. Even though Leale – who had seen plenty of gunshot wounds in his work at an Army hospital – had pronounced Lincoln’s wound as mortal, he held Lincoln’s hand for much of those nine hours, “to let him know,” he said later, “in his blindness, that he had a friend.”

There was one other, novel treatment Leale gave Lincoln, Magaña says: mouth to mouth resuscitation.

“I found a little academic article and I fell back in my seat when I read it,” she told me. “How did this man have the courage to perform this measure that had fallen out of fashion? It was a mystery I couldn’t resist.”

Mouth-to-mouth had been used by midwives for generations, and by doctors in maritime cities such as Amsterdam in the 18th century, where drowning was a leading cause of death. But elsewhere, and by the 19th century, it had fallen out of fashion. “Physicians considered the practice vulgar,” Magaña said. “Also, you were going against God’s will” to revive someone who appeared dead.

By the Civil War, the preferred resuscitation method was what everyone knows from cartoons: raising and lowering the arms. “Out goes the bad air, in goes the good air,” as Magaña puts it. “Between 1850 and 1960 there were more than 100 methods of manual resuscitation.”

When that didn’t work for Lincoln, Leale tried old-fashioned mouth-to-mouth: “The man is desperate. There’s the president in front of him. He says, ‘I leaned forcibly forward directly over his body, thorax to thorax, face to face, and several times drew in a long breath, then forcibly expanded his lungs and improved respiration.’ ”

Some question this, because Leale doesn’t mention it in his brief initial report just hours after the assassination, only in a longer, later one. And that 1909 account, Magaña believes, is partly responsible for the modern revival of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation; a month after Leale spoke of it in 1909, the highly regarded medical journal the Lancet published an article about mouth-to-mouth, giving it the author’s approval. Mouth-to-mouth became part of the lifesaving formulary again, eventually adopted by the military and the AMA.

Leale was invited to Lincoln’s autopsy; he declined. He was also invited to the funeral and accepted. When Leale returned home from his duties, said Magaña, he took to his knees, and heard a voice saying, “Forget it all.” Except for a few other brief official reports, Leale did not address the matter publicly again until the Lincoln centenary of 1909.

Magaña’s second-hand brush with the Lincoln assassination left a powerful imprint. “There is no picture, no living witnesses, no final authentication of what Leale did, but his care did extend to Lincoln’s last breath, to give him and his family the privacy to say their goodbyes and the time for the nation to brace itself for the news that Lincoln had died.”

Follow Patt Morrison on Twitter @pattmlatimes

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.