The legacy of slavery is not gone with the wind

- Share via

Reporting from RICHMOND, Va. — I was shuffling along a path beside the James River in the hot Southern sun, tied loosely by a rope to 17 other people while an actor dressed as an 18th century slave overseer paced beside us screaming demeaning, racist epithets. The thought crossed my mind that this was the height of white privilege: paying for the chance to experience a few minutes of slight discomfort (knowing the tour bus and lunch were just around the corner) so that I could get a hint of what slavery felt like.

Still, the experience was illuminating. I knew it was all theater, yet I kept my head down and my eyes averted to avoid the faux slave driver’s wrath. To maintain balance and keep an awkward, slow pace, my left hand gripped the shoulder of the young black man ahead of me. He was a senior from the University of Washington named Jarrod Stout, and his feelings about this experience were certainly more intense than mine. Jarrod was consumed by the horrific realization that people who looked like him had been pulled from slave ships at this very spot.

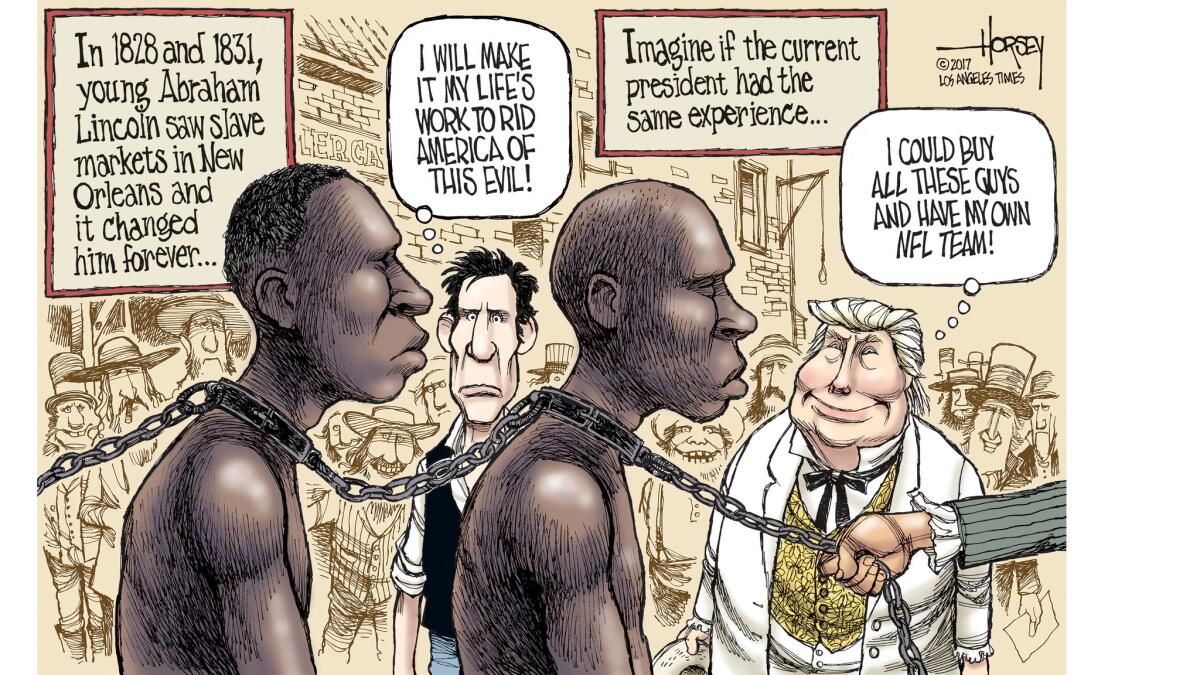

After being stolen away from their homes and families, the enslaved Africans had endured weeks of shipboard confinement in cramped, stifling gloom, chained up with other luckless strangers, hungry, naked, awash in their own bodily waste. When they arrived in Richmond — the city second only to New Orleans as a prime American portal for the trans-Atlantic slave trade — they were shackled into lines and marched down the path to the pens in which they would be kept until being sold off to the highest bidder on the slaver’s auction block.

All Americans know at least a little about our country’s shameful history of slavery, and many think the problem was resolved when the Civil War ended 152 years ago with the defeat of the rebellious Southern states. In reality, though, slavery morphed into 100 years of segregation, economic disadvantage, rights denied and racist terrorism for African Americans. And now, even after the advances of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ’60s, systemic issues remain: mass incarceration, unequal educational opportunities, economic disparities, political disenfranchisement, police violence.

Judging by the fearful ignorance displayed by too many white Americans, not only are these systemic issues not recognized as valid, but even bringing them up in polite conversation or a political campaign is an offense against their conception of what America is and should be. As we have seen in recent days, NFL players raising such concerns during a pre-game singing of the national anthem will even cause the president of the United States to respond with an angry tweet storm.

I am one white American who believes this country I love cannot be as good and great as it should be until these issues are confronted. So, for five days in mid-September, I joined with an interracial, intergenerational collection of men and women under the auspices of Project Pilgrimage, a new organization based in Seattle that promotes engagement with the civil rights issues of our day. One method of engagement is taking diverse groups on immersive pilgrimages to places where both contemporary and historical struggles can be directly experienced.

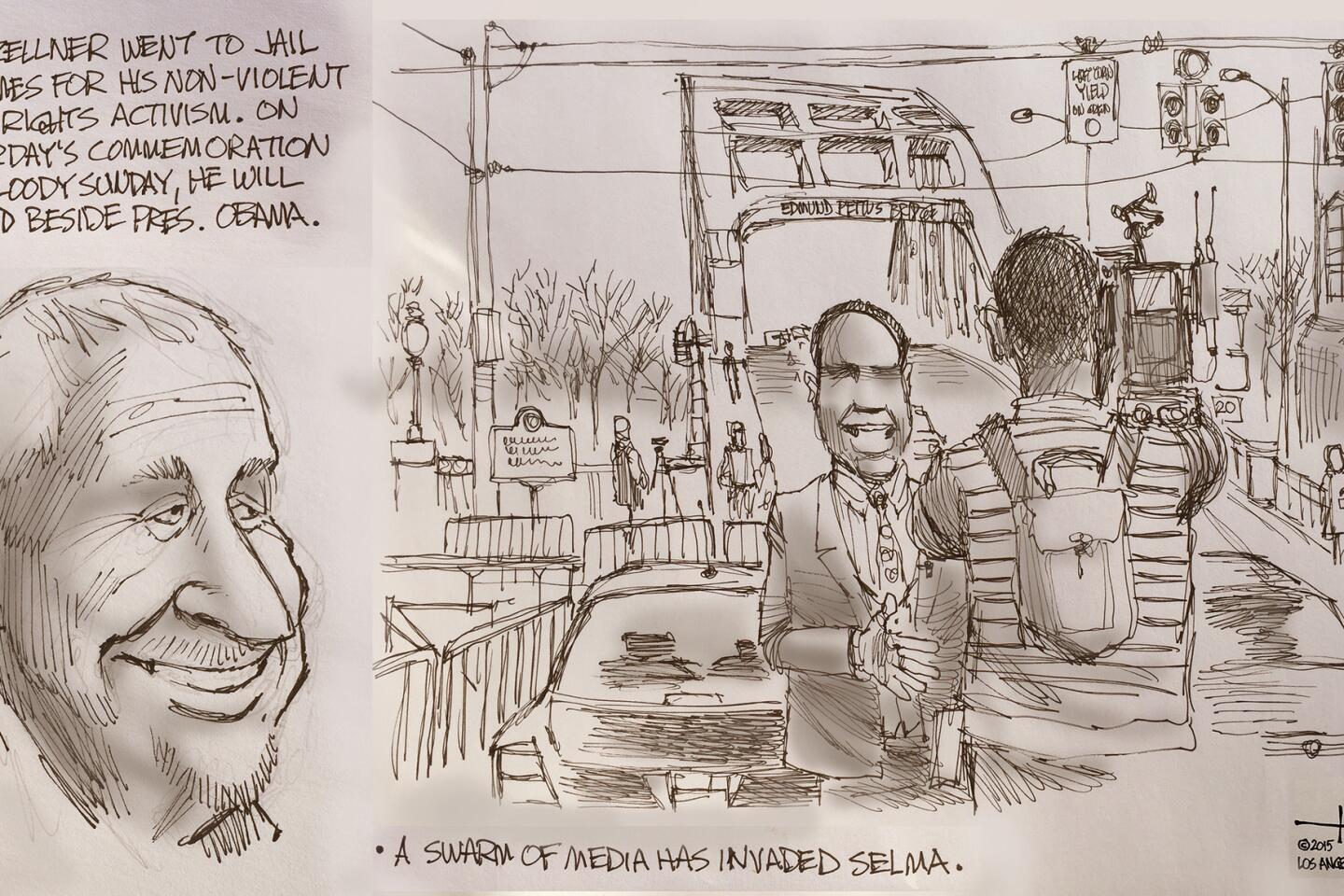

Two years ago, I traveled with a similar group through the South — to Birmingham, Ala.; Little Rock, Ark; Memphis, Tenn.; Montgomery, Ala.; the Mississippi Delta and finally to Selma, Ala, for the 50th anniversary commemoration of the pivotal Bloody Sunday march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge that helped drive passage of the 1965 Civil Rights Act.

This time around, the group included a college professor, a county official, a former legislator and other older adults paired with university students and recent college graduates. The itinerary would take us to Charlottesville, Va., where, in August, neo-Nazis paraded with torches and a young female counter-protester was killed. We would go to Harper’s Ferry, W.Va., where the abolitionist John Brown tried to incite a slave rebellion in 1859 and where, at a black college on a hill, the civil rights movement was born. We would trek across the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pa., where vast armies of white Americans fought and killed each other to settle the question of whether blacks in this country would be slave or free.

First, though, we would spend a day in the capital of the old Confederacy, to witness firsthand the debate about monuments dedicated to the Southern heroes of the bloodiest war in the nation’s history — a debate that suggests that, in significant ways, the Civil War did not end conclusively in 1865. Rather, it continues to flare up with each new generation.

This is part one of a five-part series.

Tuesday: Monuments to a lost cause.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.