One mother spent a decade after her daughters’ deaths changing car-rental laws

- Share via

Reporting From Washington — Raechel and Jacqueline Houck had a five-hour drive from their mother’s Ojai home north to Santa Cruz. They wanted to see some friends along the way and Raechel had to work that evening, so the sisters hugged their family and, with Raechel behind the wheel, drove off in their rented PT Cruiser.

Raechel, 24, had just returned from two years in Italy and had come south to be fitted for a bridesmaid’s dress for a friend’s wedding. Jacqueline, 20, was about to travel to Central America for a few months and promised her mother they’d see each other soon.

“I did not know this would be the last time I would ever see them, hold them and kiss their precious faces,” their mother Cally Houck would say years later, when testifying on Capitol Hill about their deaths. “Hours later, I received the phone call dreaded by every parent.”

Midway into the drive north, the PT Cruiser swerved off Highway 101 near Bradley north of Paso Robles and crossed the grass median. It hit a southbound 18-wheeler and burst into flames. The Houck sisters were killed.

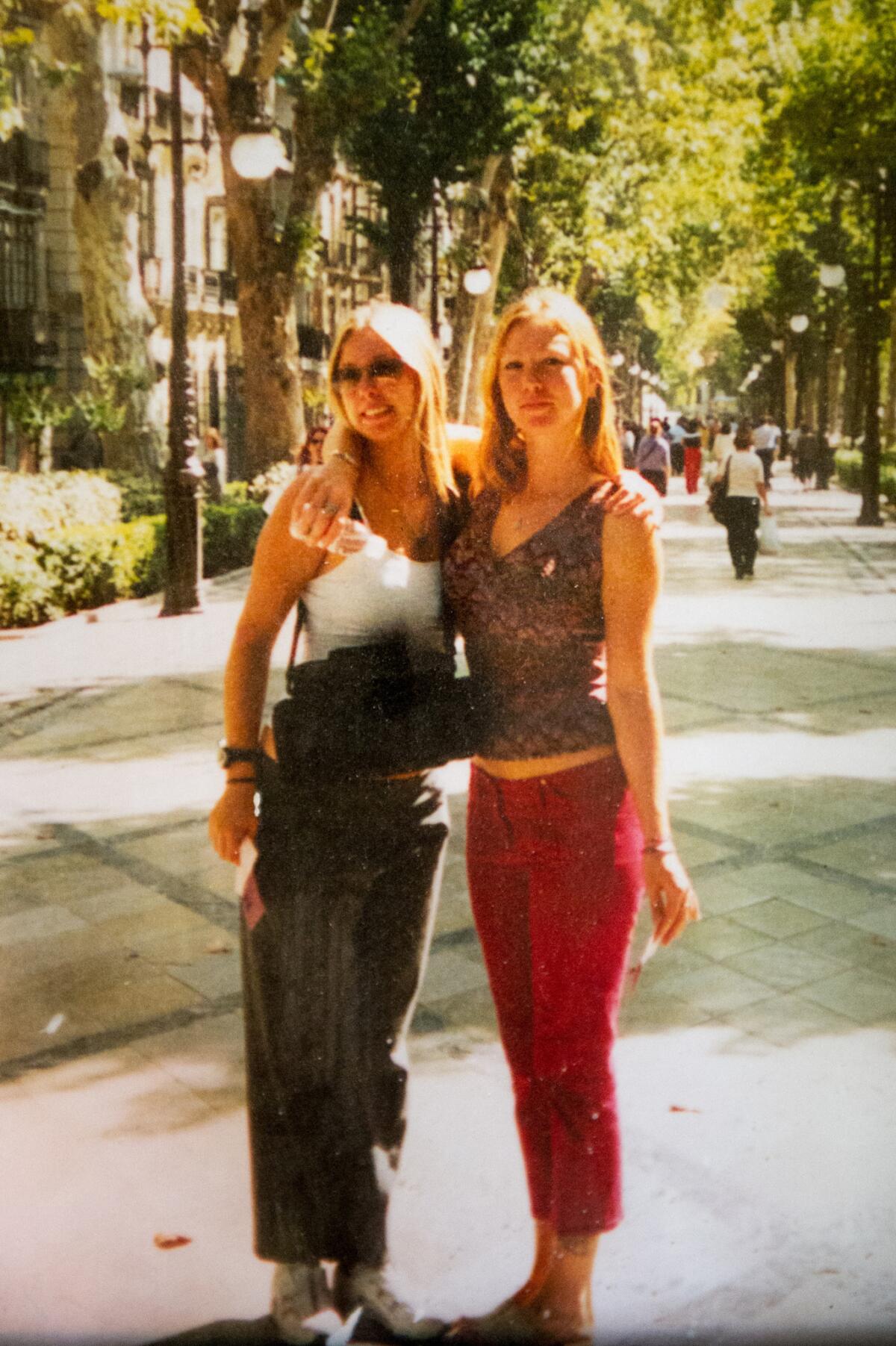

Jackie Houck, left, and her sister Raechel. They were killed in 2004 when they lost control of their rental car and it swerved into a truck.

The odyssey that began in 2004 with a mother’s grief ended this month as the names Raechel and Jacqueline Houck became part of federal law.

Lawyers for Enterprise, the company that rented the vehicle, blamed Raechel’s driving and at one point implied that she had committed suicide.

But minimal digging by the Houck parents found a recall order had been issued a month before the crash for a faulty power steering hose that could cause a fire and lead to loss of steering.

Enterprise had rented out the vehicle the Houck sisters died in three other times that month. And there was nothing legally prohibiting Enterprise or any other rental company from doing so, or requiring the companies to tell consumers about the car’s status.

“I lost my girls because of corporate malfeasance,” Houck, an attorney, said in an interview. “This wasn’t an accident, it was a crash, but it could have been reasonably avoided had a law been in effect that required a rental car company to fix a car before renting it out.”

The family took Enterprise to court, wrangling with the rental company over delays and extensions before the case was scheduled for trial. Testimony prepared for the trial revealed it was Enterprise’s policy to routinely rent recalled vehicles to the public without repairs.

“(A)t the corporate level, their philosophy was that, ‘If all you have are recalled vehicles on the lot, you rent them out,”’ Mark Matias, a former area manager for Enterprise of San Francisco, said in court documents. “It was a given. The whole company did it.”

Shortly before a trial began, Enterprise admitted 100% liability. In 2010 an Alameda County Superior Court jury ordered the company to pay $15 million to the Houck parents.

Consumers for Auto Reliability and Safety President Rosemary Shahan said Houck called her California-based advocacy group for advice and support during the family’s five-year legal fight. Shahan said until then, she hadn’t realized rental cars weren’t covered by the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration.

She urged the Houcks to decline the $3 million Enterprise had proposed as an out-of-court settlement in exchange for signing a confidentiality agreement.

“We needed her voice,” Shahan said.

Cally Houck stands in the backyard of her Ojai home

Not signing a confidentiality agreement meant Houck was free to tell her daughters’ story. So she spoke on television and testified before a Senate committee to bring the human element to a legislative push.

“I had a standard. If it would have saved my daughters, it’s a good law. If it wouldn’t have, it’s no use,” Houck said this month Washington.

When Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) filed the first version of the Houck Act in 2011, with California’s Democratic Sens. Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein on board, rental companies balked.

The bill never had a hearing. Members filed it again in 2012, and the next year, and on and on, inching closer, gaining allies and converting opponents.

Boxer first met Houck in person in March 2012.

“The minute I had that face-to-face meeting, I knew there was no way I was going to stop until we fixed this,” Boxer said. “You can’t turn away from Cally, you can’t.”

When legislative attempts stalled a few months after the meeting, Boxer asked the country’s largest rental car companies to sign a pledge promising “to not rent out or sell any vehicles under safety recall until the defect has been remedied.”

After 30 days, Boxer announced that Hertz, which already had a policy in place, had signed the pledge. After a deluge of news coverage and an online petition with more than 150,000 signatures, the holdouts relented.

An Enterprise spokeswoman credited “the courage and determination of Ms. (Cally) Houck in response to the loss of her daughters” when announcing the company would support the legislation.

Though Houck was initially suspicious of the change of heart, “the rental car companies became our greatest partners in this,” she said, describing them as “sincere.”

In May 2013, the legislation finally got a hearing. Houck testified. “Nobody should have to endure the loss of a loved one because a rental car company didn’t bother to get an unsafe, recalled car repaired,” she said. “This is simple to fix. This is doable now.”

At the hearing, officials with the National Automobile Dealers Assn. and the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers said they had concerns the bill was too broad and would harm small auto dealers who only loan out a handful of vehicles.

No agreement was reached that year.

But in 2014, after facing legal trouble over massive recalls due to a faulty ignition switch, GM (a member of the the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers) joined the effort. Honda followed suit this summer amid a recall over Takata airbags.

Boxer, House sponsor Rep. Lois Capps (D-Santa Barbara) and their colleagues plunged ahead this spring, getting the language included in the $305-billion, five-year highway funding bill.

The National Automobile Dealers Assn. argued dealers would suffer because recalls can take months to occur and can sometimes be ordered for not immediately pressing safety issues. The group said in a statement at the time that the ban would affect how much consumers received for trade-ins because dealers would have to weigh the costs of a vehicle possibly sitting in the lot for months.

When the highway bill reached the House floor, GOP Rep. Roger Williams, who owns a car dealership in his home state of Texas, added an amendment to exempt car dealers’ rental or loaner car fleets.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“Vehicles would be grounded for weeks or months for such minor compliance matters as an airbag warning sticker that might peel off the sun visor or an incorrect phone number printed in the owner’s manual,” he said when introducing the amendment.

The National Independent Automobile Dealers Assn. agreed, and said in a statement that the measure without the amendment “could cripple them or put them out of business entirely.”

House and Senate leaders reached a compromise to exempt only dealers that rent or loan out fewer than 35 cars. Capps and Boxer each said removing the exemption in future law is a priority. Houck said she will keep fighting.

Both lawmakers are retiring, and will leave Congress in one year. For Boxer, passing the highway funding bill was a relief: “This is one of the things that was on my plate that I knew I had to do.”

It’s rare to see citizen efforts become law. The most prominent recent example was in 2014, when Congress passed legislation sponsored by then-House Majority Leader Eric Cantor of Virginia to fund pediatric research. Gabriella Miller used YouTube videos to advocate for heightened awareness of pediatric diseases. She died of brain cancer in 2013 at the age of 10.

UC Irvine associate political science professor Matthew Beckmann said that with so much competing for the attention of members of Congress, citizens with a stake in an issue are only occasionally able to build a coalition of lawmakers and interest groups to get something passed.

“When people do it, they really should be commended,” he said. “It’s neat to see a case where someone invests in something because they truly believe in it and the system truly works.”

Capps said the Houck Act demonstrates that anyone with a problem can petition their representative for a fix. She said she wanted the Houck daughters’ names to be part of federal law, to know that there was some peace to a tragic story.

“To me it was important that this be connected to real people or to real lives,” she said.

There were “a lot of tears” when Houck visited Boxer and the other members on Capitol Hill, and the senator gave Houck a signed copy of the legislation bearing her daughters’ names.

Houck gestured to the names of the lawmakers who helped, calling them “our champions and our voices.”

But Boxer said it wouldn’t have happened without Houck: “I told her, ‘You turned tragedy into the most inspirational advocacy I’ve ever seen.’”

ALSO

These California lawmakers don’t live in the districts they represent

Officials and family paint different portraits of suspect in Vegas rampage

Pasadena police fumbled their investigation of a black teen’s shooting, report says

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.