The Ultimate Team Player Goes It Alone : Off the Court, Larry Bird Leads a Singularly Unremarkable Life

- Share via

When the National Basketball Association held its awards banquet in Salt Lake City last June, most people there wondered if Larry Bird would show up to collect the trophy as the league’s most valuable player.

Ralph Sampson, the rookie of the year, was there. So was Adrian Dantley, the comeback player of the year. But for a time, it appeared that Boston’s Kevin McHale, who was being honored as the best sixth man in the league, would have to accept the MVP award for his Celtics teammate.

Just before the ceremonies started, though, word spread that Bird had indeed landed. Some knew all along that he would be there, given the nature of the honor. He had been runner-up the three previous seasons, and he wanted this one.

But even those who predicted his presence weren’t prepared to deal with what they saw. Amidst the finery and expensive designer suits, Bird arose to accept his award in a short-sleeved sport shirt and blue jeans.

More than a few people were disgusted.

Frankly, Larry Joe Bird didn’t care.

“All I know is that it was summer, which is vacation time for me, and I wear what I want to wear when I’m on vacation,” he said recently. When the league called him at his home in French Lick, Ind., to ask him to attend the ceremony, he was mowing the lawn.

“It would have been a lot easier for them to just put the award in a box and send it out to Boston, and we could have had a nice party there,” he said. “I knew it was a banquet and all that, but I didn’t care. I hate doing things like going to restaurants where you have to wear coats and ties. What for? All they want is your money, feed you and get you out.

“Just because the league wanted me to do something didn’t mean I had to. The funny thing about people being mad because I didn’t wear a suit is that I could buy two to their one, so what’s the difference?”

If the truth be told, he could come up with a higher suit-per-person ratio than that -- but he doesn’t want to. Even the hallowed Boston Celtics have learned that he is very much his own man.

“I’ve been around Larry enough to know better,” says Jan Volk, the team’s general manager. “Up to that point (the time of the banquet), I don’t know if I’d ever seen him in a coat and tie. I’d have been surprised if he had worn one.”

It has been widely chronicled that Bird transferred from Indiana University in 1974--he was there less than a month--because he couldn’t stand Bob Knight and was intimidated by a school with 33,000 students. Yet, in a recent Time magazine cover story, it was brought out that perhaps the true reason wasn’t Knight (“He would have loved my game,” Bird said) or the size of the school, but rather the depth of the closet of his first roommate -- fellow player Jim Wisman.

It is perhaps no small coincidence then that his closest friend on the Celtics, guard Quinn Buckner, is a lot like Bird, both in the casual attitude toward clothing and the connection to Indiana basketball. Buckner, who played for Knight and the Hoosiers in 1972-1976 and captained the U.S. Olympic team after his senior season, was traded to the Celtics before the 1982-83 season.

Upon arriving in Boston, Buckner says, “I sought Larry out. We would have played together at Indiana. I wasn’t around when he left. Had I been there, maybe things would have been different. I think I just wanted to talk about what was going on there at the time, but we became friends. I’m not sure why he likes me; maybe it’s because we have the same approach to the game -- not that we have the same tools. Maybe it’s just that Midwestern lack of flair.”

When people in French Lick talk about the fabric of life in their community, it’s highly unlikely they’re referring to Italian knits or wool blends. Although the town is nestled in Orange County, the difference between it and its southern California counterpart is far greater than 2,000 miles. Named after a fort near where animals used to lick the minerals from natural springs from their fur, French Lick’s claims to fame are the Kimbro Piano & Organ Co. and a vacation resort most of the populace of 1,800 probably could do without.

Another claim to fame, of course, is basketball. The gym at Spring Valley, the local high school with its permanent--not rollaway--bleacher seats, is a monument to the game, yet it’s only one of 10 indoor courts in the town. There are another 21 full courts outdoors, including the one--complete with glass backboards--next to Bird’s home. Is there any wonder that Indiana University and now Boston represent extreme forms of culture shock? “I never had the opportunity to travel when I was younger,” Bird says. “You always think you’re old enough to handle things; when you’re 15 you want to party all night, when you’re 20 you think you can drink as much as you want, and when you’re 21 you figure you can do whatever you want, whenever you want.

“It’s not that way, though. For me, being in Boston is like going from French Lick, with 1,800 people, to Terre Haute, with 50,000. Now there’s millions of people to deal with. If I had a son that had to go from Terre Haute to Boston I’d be scared to death for him. Now I know why my mom was so scared when I left.”

In Boston, he leads a singularly unremarkable life, as is his wish. He was briefly married to a high school sweetheart. There’s now a Significant Other in his life, one Dinah Mattingly, but the subject is strictly taboo for the media in dealing with Bird. That relationship--Bird and the press--gradually has improved over the years. During his all-America days at Indiana State, he often ignored requests for interviews, a practice that continued his first year in the NBA.

He didn’t do it in disdain; it was an example of the consummate team player looking out for his teammates.

In the locker room after a recent Philadelphia-Boston game, he looked at the media madness that typically accompanies that rivalry and smiled when asked if he, indeed, had become more comfortable with the press.

“I was never really uncomfortable with them,” he said. “It was just a case of everybody wanting to talk to me and not with the guys I was playing with. They work hard, too; they deserve to get a little sugar.”

Although league rules provide access to the locker room after a 10-minute cooling-off period, the training room remains off limits. And the Celtics’ starters -- who, along with sixth man McHale, average more minutes played per game than any other team in the league -- spend a lot of time there.

Writers with pending deadlines often have to get detailed analysis from such little-used players as Greg Kite and Rick Carlisle. Eventually the mainstays emerge, almost in reverse pecking order: M.L. Carr, Danny Ainge, Cedric Maxwell, et al.

It is perhaps fitting that the last beak to show is Bird’s, often 45 minutes after the end of the game. Still, he has to work his way through a mass of humanity. Without apologizing for blown deadlines, he explains his never-varying routine: “It’s just easier this way. I could come out right away and there’d be one guy, and I’d go away and come back and there would be three more asking the same question. This way, everyone knows when I’m coming out; they can wait if they want, and we’ll get it all done at once.”

Such kingly bearing is entirely appropriate in Boston, which in this, the era of Bird, could be his oyster if he so desired. “Larry Bird, and sometimes McHale; that’s how it is here (in terms of recognition and publicity),” center Robert Parish says. “That’s how it’s going to be, too. There’s no need to worry about it. For most people, I’m the same as Maxwell, just another player.”

Yet, according to Dennis Johnson, inside the Celtics’ locker room, there’s really no difference between starters. “I’ve never seen him get beside himself because of who he is,” Johnson says. “He gives it and takes it, too. Everyone gives him as much trouble when he shoots an air ball as anyone else would get, and he accepts it in that fashion.”

Usually, though, Bird is on the giving end, and not only because he shoots fewer air balls than most players. According to Coach K.C. Jones, “Larry just doesn’t miss much. You put all the media and cameras in front of him and he puts out the same old routine answers. People think he’s dull, that there’s not much to him.

“That’s a lie. His wit is a lot like Will Rogers’. The other guys put him down, but he’s never topped.”

It was Bird who, when asked by Ainge, what he should do against Magic Johnson of the Los Angeles Lakers, replied, “Just try and stop him from getting a triple double before the end of the first quarter.”

There is often a cutting edge to Bird’s humor, a sense of sarcasm that often, particularly when pointed at teammates, takes on the aspect of a challenge. It’s not enough that he will say, flat out, that if McHale isn’t in just the right spot to receive a pass, Bird will shoot the ball because, “If I threw it to him, there’s no way Kevin would ever catch it.”

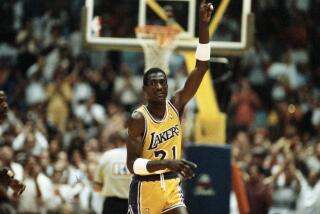

There also has to be the needle. When discussing the difference between himself and the Lakers’ Johnson, the two men who entered the NBA together in 1979 and generally are recognized as the best all-around players in the league, Bird says, “We’re just different types of players. I don’t think he’s ever gone into a game where he’s had to score 30 points for his team to win. Look, he’s got Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to throw the ball to; I’ve got Kevin McHale.”

Yet, when McHale set the team record of 56 points in a game March 3, it was former record holder Bird who assisted on the basket that broke the record and fed McHale for another four baskets in the final period.

It was also Bird who scored 60 in a game less than two weeks later.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.