Rise and Fall : by Milovan Djilas, translated by John Fisk Loud (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: $19.95; 367 pp.)

- Share via

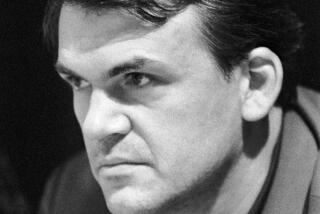

Here is another memoir from the long and tempestuous life of the Yugoslav dissident who became one of the world’s most authoritative and incisive critics of communism. Milovan Djilas, the one-time propaganda chief of Communist Yugoslavia, confidant of Marshal Tito, and the author of the devastatingly revealing “Conversations With Stalin,” turns to his journey of disillusionment that led to his political transformation and banishment from the Yugoslav establishment.

Djilas’ previous memoirs cover his childhood and youth as the son of a proud Montenegro family and Communist revolutionary. Then came his reminiscences of his struggles as a World War II partisan chieftan at Tito’s side.

This latest effort starts with the years immediately after the war when Djilas and other Yugoslav Communists were, as he writes, “more Bolshevik than the Bolsheviks.” It ends with Djilas’ release, in 1966, from the second of the two prison terms, totaling nearly 10 years, he served for his heresy in attempting to foster democratic pluralism in Tito’s Yugoslavia.

In between, Djilas tells of his feelings during Yugoslavia’s historic break with the Soviet Union in the late 1940s. He recalls his growing contempt for Tito who, seduced by dictatorial power, was, in Djilas’ eyes, transformed from the lean, hard partisan leader he admired and served faithfully into a vain, imperious, “corpulent, carefully uniformed body with its pudgy, shaven neck (that) filled me with disgust.”

Perhaps, because of his advancing years, Djilas, now 73, appears intent in settling accounts and setting the record straight. There are digressions that slow the pace of the book. He repeatedly returns to his previous works, offering elaborations on issues and views that he fears may have been misunderstood.

He offers capsule opinions of some of the personalities, both within Yugoslavia and without--friends, foes and friends who became foes after his fall from power in 1956. Many are individuals little known in the West--native artists, writers, poets, architects. Others are--or were--major figures on the international scene. There are, for example, Polish leader Wladyslaw Gomulka, whose modesty “was too modest, too contrived not to be suspect,” and Czechoslovak Foreign Minister Jan Masaryak, who “made no effort to conceal his passion for women.”

One of his appraisals contains an inconsistency. He portrays the Bulgarian Communist leader Georgi Dimitrov as “faint-hearted and at a loss when facing Stalin.” Yet a few sentences later, he implies that Dimitrov was murdered at Stalin’s order because of his independence. Djilas writes: “I still think that even though Dimitrov was ailing and diabetic, he did not die a natural death (in 1949) in the Borvilo clinic outside Moscow. Stalin was wary of self-confident personalities, especially if they were revolutionaries . . . .”

Clinging to his convictions, Djilas, in his best chapters, tells of his “withdrawal into empty isolation behind my moral defenses” in his refusal to recant. He calls the party’s denunciation of him before a Central Committee meeting a “Stalinist show-trial, pure and simple.” He adds: “Bloodless it may have been, but (it was) no less Stalinist in every other dimension--intellectual, moral, political.”

Djilas displays no false modesty here. While works of this kind often serve as a vehicle for self-justification, Djilas’ strength and courage in the difficult years of his imprisonment and its aftermath are clearly established. And there are no regrets.

“The road I was on,” he writes, “was of my own choosing.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.