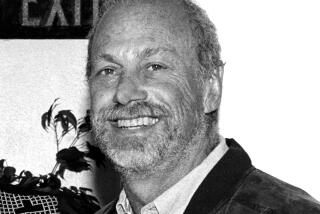

Alan Livingston Winds Down to Two Careers

- Share via

“You can achieve anything if you want it badly enough,” says Alan Livingston, echoing an adage he first encountered half a century ago, during the Great Depression.

Through the years, he has rediscovered the truth of the adage many times. In his youth, for example, he dreamed of attaining financial independence and of marrying a beautiful woman.

He married the woman: Nancy Olson, film actress (Academy Award nominee for “Sunset Boulevard”) and arts activist (currently chairman of the Amazing Blue Ribbon, the Music Center fund-raising group). And he also achieved financial independence.

No Unfinished Tasks

Quick and inventive by nature, he is a perfectionist who refuses to leave a task unfinished; his diligence and persistence border on the obsessive.

He has tackled a series of careers, having been at one time or another a professional musician, liquor salesman, writer and producer of children’s records, business executive and television mogul.

Widely recognized on the Los Angeles social scene, he is quiet and reserved. Guests at dinner parties have observed many times that Livingston seems content to listen to others while saying nothing about himself.

But the quiet man, at 67, is, in fact, busily involved in two careers. He is an investment adviser, and he is also on the verge of achieving recognition as a writer, having turned one of his youthful fantasies--plus his musical background--into a novel and a screenplay, “Ronnie Finkelhof, Superstar.”

The book is scheduled to be published in 1986 by Random House, to coincide with release of the film version, currently slated to be made at Warner Bros., with Livingston as co-producer (his partners: Richard Zanuck and David Brown).

The title hero is, Livingston said, “an extremely shy and unpopular high school student who, through a series of strange events, becomes the No. 1 rock singer in the country.”

Livingston, the one-time boss of Capitol Records who signed such groups as the Beatles and the Beach Boys, explained in an interview that Ronnie Finkelhof is “a totally fictitious character, more than anything a figment of my own childhood dreams of becoming someone important. But in terms of the record business, the details are authentic. There is nothing in the story that could not happen.”

No Desire to Sell Shoes

Music enveloped Livingston’s youth. The youngest of three children, he grew up 17 miles from Pittsburgh in McDonald, Pa., a town of 3,000. “My father was placid and easygoing,” Livingston recalled. “He owned a small shoe store where I helped out on Saturdays. I think he’d have been pleased if I’d made a career of working in the shoe store. But my mother was ambitious. She encouraged us to read books, and she pushed us toward a musical education. That was fine with me, because I wanted no part of the retail shoe business.”

Alan took saxophone and clarinet lessons while his brother, Jay, studied piano. (Years later, with collaborator Ray Evans, Jay became an Oscar-winning songwriter whose credits include “Mona Lisa,” “Buttons and Bows,” “Que Sera Sera” and “To Each His Own.”)

At the University of Pennsylvania, 300 miles from home, Alan and Jay organized an orchestra to play at fraternity dances and school functions. The Depression-era dollar went a long way. “I earned $5 a night as a musician,” Alan Livingston said, “and it paid my expenses, including $5 a week for room and $1 a day for food.”

Alan hustled to find summer bookings for the band on cruises and at resorts. He said: “One time on Long Island, after we worked two weeks at a nightclub, the place folded without paying us. We had no money. We were renting a Packard for $1 a day. We kept driving, arrived at a hotel and asked the manager to hire us. He declined, saying he already had an orchestra.

“We could have walked out, but I kept remembering that maxim about wanting things badly enough. So I told the group: ‘I don’t care what he says, let’s show him what we can do.’ We got our instruments from the car, sat down in the lobby and played music. The guests came around and applauded, and so did the manager’s wife. The manager fired the other orchestra and hired us.”

Fine Arts Studies

Livingston began his college studies in fine arts (“I thought about becoming a writer”) but later transferred to the university’s Wharton School of Finance “because it seemed like a good idea to learn more about business.”

For a senior thesis, he researched the liquor industry’s advertising problems--Prohibition had been repealed several years earlier, but temperance groups continued to denounce liquor ads--and after graduation he rushed around in search of a job with an advertising agency.

The Depression-era job market appeared hopeless. But Livingston’s persistent nature, plus a willingness to flash his senior thesis, eventually helped him to land a $15-a-week job at Schenley Distillers as a trainee. He peppered the company suggestion box with promotional ideas, and soon competitor Calvert hired him away--as a $17-a-week trainee.

Calvert’s training began with a sales assignment. “By sheer coincidence,” he said, “they put me in a territory near home, among the steel mills and mining towns of western Pennsylvania, all of it hit hard by the Depression. Most whiskey sold in that area at 10 cents a shot, including a Calvert brand called Old Drum, but its sales were minuscule.”

Rebuffed repeatedly in his efforts to drum up sales, Livingston decided “to take a creative approach.” He visited bars and “instead of introducing myself as a Calvert salesman, I simply bought drinks for people and said I’d heard that Calvert was putting its most expensive brand--Lord Calvert--into Old Drum bottles in order to increase sales of Old Drum.”

Livingston said recently: “It was a misleading, underhanded tactic. I’m not particularly proud of it. But I had to survive.” The message that Calvert’s best whiskey was available at 10 cents a glass became a major topic of barroom conversation and resulted in skyrocketing sales. Impressed, Calvert management soon named Livingston East Coast sales promotion manager and raised his pay to $50 a week.

Enlisted in the Army

When the World War II draft drew near, he enlisted in the Army, “but I hated being a private and made up my mind to become an officer.” Nearsightedness threatened to block his way. “I memorized the eye chart, which is very difficult, because it doesn’t spell anything. When the doctor examined me, he said: ‘It’s amazing. You’re nearsighted, but you have the power to pull your muscles into focus.’ I said, ‘Is that right?’ And he OK’d me.”

At war’s end Livingston opened a copy of Life magazine featuring a life-style story on Southern California. “It told about people earning $10,000 a year, single-family houses, backyard swimming pools. I thought, ‘Wow, that’s for me.’ ”

He hitched a bucket-seat ride on an Army plane and, arriving in Los Angeles, “I decided to combine my musical background, business education and creative abilities--and go into the record business. The large record companies--Columbia, RCA Victor and Decca--were headquartered in New York. I figured there was more opportunity at a very small record company based here, Capitol Records.”

Capitol’s executives hired him at $100 a week to create new records. Recalled Livingston: “My first move was to write and produce a record called ‘Bozo at the Circus.’

“As a child I’d played records all the time, speeding them up or slowing them down to achieve certain sound effects. This time I hired a former circus clown and I tried various devices to create a slow, low voice for an elephant, and a fast, high-pitched voice for a hyena. Then I put it together with a book of pictures.

“Bozo’s voice narrated the record, telling listeners: ‘Whenever I blow the whistle, turn the page.’ And on every page there was a different animal and all this was accompanied on the record by a series of animal voices. It was a new concept, and I called it a ‘record-reader.’ It had tremendous sales and then I followed up with other Bozo albums.” Livingston wrote a song: “I Taut I Taw a Puddy Tat,” which quickly gained worldwide popularity.

Livingston also put together other albums of record-readers, including “Sparky’s Magic Piano.” He obtained licensing agreements from Warner Bros., Disney and other studios, allowing Capitol to make albums of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Woody Woodpecker, the Three Little Pigs and numerous other characters.

As sales soared, other companies rushed into the market with record-readers. Capitol, fast becoming a major company, upped Livingston to vice president. Along the way he signed Frank Sinatra, whose recording career had temporarily faltered, to a long-term contract. One Capitol song, “Young at Heart,” sent Sinatra’s sales climbing again.

Not every decision was brilliant. When Livingston was offered a tune called “Rudolph the Rednosed Reindeer,” he rejected it as “the most ridiculous song I’ve ever heard.” Another time, after attending an audition for the Broadway musical “West Side Story,” Livingston vetoed any backing by Capitol because, he said, “I didn’t think the music sounded commercial.” But he also made shrewd guesses for the company, including a major investment in “Funny Girl,” featuring Barbra Streisand.

Hired by RCA

RCA hired Livingston to be its vice president in charge of NBC television programming. In that post he supervised, among other shows, the development of a pilot for “Bonanza.”

Said Livingston: “I was actually somewhat embarrassed about the pilot. I hired all the leads for the show--Michael Landon, Lorne Greene, Dan Blocker, Pernell Roberts--and I found the story concept fascinating. But the pilot was needed so quickly, and had to be produced under such pressure, that the finished film--which is, after all, what you see on the screen--just didn’t look good. It was very hard to sell (to commercial sponsors) and finally had to be sponsored by RCA.” The show subsequently ran 14 years.

Livingston quit NBC after a five-year hitch, and after some friction in the executive suite. He returned to Capitol Records, this time as president, and he found that “The music business had changed. Rock had begun to raise its head. I knew nothing about rock.”

But Livingston learned. He signed the Beach Boys and, “I asked a subordinate about a group that seemed to be doing well in England, the Beatles. He dismissed them as ‘just a bunch of long-haired kids,’ so I didn’t press further. They were under contract to EMI, a British company that owned Capitol, but Capitol was run as an independent company. British records simply weren’t selling in the U.S., so for some time Capitol ignored the Beatles.

“One day their manager, Brian Epstein, called from London and said he just couldn’t understand the lack of interest in the Beatles, and would I please listen to one of their records. This time I did and I thought they were absolutely great. We began turning out their records and of course it became the most profitable experience in Capitol’s history.”

After a series of board-room moves, Capitol became a publicly traded company. Livingston, holding a bundle of stock, resigned in 1968 and sold his shares to EMI. “For the first time in my life I didn’t really have to work. I figured it was part of the American dream to be able to retire young. So I bought a set of golf clubs and announced I was going to play.”

The Livingstons, who live comfortably in Beverly Hills, were married in 1962. They have one son, Christopher, 20, a college student, as well as children by previous marriages. Nancy was married earlier to songwriter Alan Jay Lerner, who dedicated “My Fair Lady” to her. Alan Livingston had two earlier marriages, including one to singer-actress Betty Hutton.

Took Up Golf

When Livingston in 1968 announced his decision to retire from business and take up golf, “Nancy looked at me in absolute disbelief. She knew I couldn’t retire. And she was right. I got bored very fast.”

With backing from investment bankers, Livingston set up a company called Mediarts to finance the production of movies, including “Downhill Racer,” which starred Robert Redford, and records, including an enormously successful album, “American Pie.”

Livingston next decided “to create income with my funds. I had a business education, going all the way back to college days, but I was not really sophisticated in the stock market.” Eventually he became a general partner in three investment funds.

His agenda seemed full, yet something was missing. “I’d always wanted to write a book. So I began waking up mornings at 6 and writing at home for three hours before going to the office. Saturdays and Sundays were spent at the typewriter. At Christmas, we usually go skiing in Sun Valley. I took along my typewriter and, while everybody skied, I sat in the condominium and wrote all day long.”

‘Maybe One Is Enough’

At the end of nine months he had completed “Ronnie Finkelhof, Superstar.” Livingston has no immediate plan to write another because “Maybe one is enough.”

Meaning what? “If I start another, I’ll have to finish it. I don’t like to leave anything unfinished. I have an absolute need to see that every phone call is returned, every letter answered.

“I’ve always been very attentive to detail. It’s a characteristic that drives some people crazy. But on the other hand, when people around me are sloppy, that drives me crazy. In my case, I do have some creative imagination and some limited talents, but to the extent that I’ve been successful, I attribute 90% of it to wanting something badly enough, which means applying diligence and determination to see a job through to the end.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.