OLEG VIDOV--COMING TO THE MOUNTAIN AT LAST

- Share via

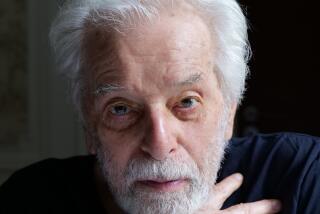

The Robert Redford of Soviet cinema, who recently defected from his homeland, arrived in Los Angeles this weekend much as his American counterpart does--very quietly.

“It’s like coming to Mt. Everest; I think I am now near the mountain,” Oleg Vidov said of the film capital of the world in his first extensive interview in the United States Saturday evening. Vidov, whose looks and popularity at the box office inspired an American critic to compare him to Redford, told The Times that “American films always transported me to a world that was nice and beautiful.”

The blond, sapphire-blue-eyed actor, who will only say he’s in his late 30s, grew up loving Johnny Weissmuller’s “Tarzan” films. He said he was amused by “The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming” (director Norman Jewison’s 1966 comedy about a Soviet submarine that inadvertently lands in New England), which he saw while on loan in 1967 to a Scandinavian film company.

“It was a film with a good heart, I just wished at the time that real Russian actors could have played Russians,” he said.

Vidov is the first leading Soviet actor to resort to the same means used by ballet dancers Mikhail Baryshnikov and Alexander Godunov. Other Soviet actors, including Sava Kramarov, a much-beloved Soviet comedic film star (seen here in “Moscow on the Hudson” and “2010”) have been allowed to emigrate to the United States.

Admittedly suffering from jet lag and some degree of culture shock, Vidov still was game for an American musical and had been provided with tickets to “Cats” that evening. “I hear those little cats are very pretty,” he said, smiling.

While he awaited the curtain, he sipped champagne and coffee in a suite at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, discoursing with intelligence and passion on a number of subjects. He spoke English with a minimum of difficulty, turning only occasionally for a word to his friend and sponsor, John Frederick.

The former stage and television actor was instrumental in helping Vidov through the defection process, turning at one point to an old actor friend, President Ronald Reagan, for assistance.

“It is difficult to go from people who love you,” Vidov said sadly, explaining that an actor’s disappearance is widely noted, given the number of moviegoers in the U.S.S.R.

“When the ballet dancers leave, not everybody knows--not outside of Moscow in the village. Many people in Moscow cannot buy tickets--it’s a very elite profession.”

However, film actors regularly travel throughout the U.S.S.R. to promote their movies--much as actors do in this country--and can become well known personalities, he said.

When his friend and colleague Kramarov left the country, Vidov said, “The government took all of his posters down from the walls. They didn’t want to have to explain why he left; it was easier just to forget.”

However, on many of Vidov’s personal-appearance tours, “the people would ask me, ‘Where’s Kramarov?’ They’d ask because they liked him and still like him. They felt something strange. I told them that he was in Hollywood and they didn’t regard it as something negative, but they were confused.”

Vidov said he “wouldn’t presume” to talk about what kind of roles he would like to play, now that he has arrived in Hollywood. “I’m just the person who came; I cannot say. If I am to play Americans, I have a great obligation to be right. I hope to bring the two nationalities closer together. I have grown in one system’s rules, dramaturgy and social law. Now, I will learn another.”

Vidov described American films as having “a lot of personality. They have a high level of discussion about the individual.” He cited “Roman Holiday,” “Papillon,” and “Kramer vs. Kramer” as films he especially liked (he hasn’t seen anything more recent than the 1979 “Kramer”). Gary Cooper, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn and Dustin Hoffman are among the actors whose work he has enjoyed.

Gracious and eager to talk despite his exhaustion, Vidov recalled the series of events that led to his defection--a decision he termed “very, very difficult”--and offered an insider’s perspective on Soviet film making.

While working in Yugoslavia (where he was so popular that his name was used regularly in crossword puzzles), Vidov accepted a part in a TV miniseries being filmed in Yugoslavia. In the four-hour series he plays a Cossack leading Germans over an old trade route to China. Picked up by Orion Pictures television division, “Behind the Sunrise” is scheduled to air here later this fall, Frederick said.

Although Vidov paid a percentage of his earnings from the project to the government as required, he said that his decision to accept the role without first obtaining official permission angered members of the government’s powerful Cinematography Committee. (He explained that the committee oversees every aspect of a film’s production, from approving the subject matter to deciding which actors may perform to editing the final version.)

Shortly after he had completed the role, Vidov was given 72 hours to return to Moscow. Rather than comply, he said he decided to defect. An Austrian actor brought Vidov an Austrian visa, the two flew to the Yugoslavian-Austrian border and prepared to drive across. Ironically, he never had to use the visa. The border guards were so engrossed in a televised soccer match that--recognizing the Austrian--they simply waved the car through.

Even before his defection, Vidov had fallen out of favor with Soviet authorities, the actor-director said.

The Soviet system of film making, he explained, rewards actors who perform in politically themed films--often paying them three times as much money as those who act in fantasies (or “fairy tales,” as he described them). Vidov said that for most of the 37 films he made in the last two decades, he consistently opted for “fairy tales.” While that decision didn’t endear him to the authorities, he said, “my public recognized and appreciated my stance.”

However, even creating Russian fables and other escapist fantasies “took a special kind of talent to maintain a film’s vision,” he said, “because the committee members had to edit a film; otherwise, why were they getting paid?”

One director, he recalled, inserted numerous shots of a white dog running about in a film. “When the committee asked about the dog, he told them it represented the freedom of the soul. They said, ‘That’s dangerous, there will be no white dog in this film.’ ”

So the director removed all of the offending scenes, ending up with the original version of the film he intended to make.

After his defection, Frederick arranged for Vidov to fly to Rome, where he stayed with actor Richard Harrison and his wife. He also met with director Franco Zeffirelli, who promised him a role in his next film--the story of the friendship between Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.