Book Review : Mistress to Wallenberg and Eichmann

- Share via

Safe Houses by Lynne Alexander (Atheneum: $15.95)

Weighed down by a cargo of imagery, burdened with an unwieldy plot, listing first to fact and then to fantasy, this ambitious novel stays afloat by sheer bravura. Using the Holocaust as her base, Alexander has elaborated upon the legend of Raoul Wallenberg, the heroic Swedish diplomat who rescued so many of the doomed. She has endowed him with a Hungarian mistress who is simultaneously, though reluctantly, bestowing her favors upon Adolph Eichmann, an arrangement possible because both men are conveniently stationed in Budapest.

Gerda is young, and by her own account, spectacularly beautiful. Her father, once a lowly butcher, has inveigled his way into an enviable position as manager of the Majestic Hotel, the last oasis of luxury in Central Europe. Paralleling Gerda’s story is the tale of Hanno Baum, a precociously talented pastry chef. When “Safe Houses” opens in 1956, both Gerda and Baum are middle-aged exiles living in Brooklyn. She’s supporting herself comfortably as a call girl, never leaving her apartment; one of the various “safe houses” of the title.

By this time her daughter, who could be either Wallenberg’s child or Eichmann’s, has grown into a remarkably unattractive adolescent, rail thin, with blackened teeth and a cringing manner; hardly an appropriate or lovable offspring for the still glamorous Gerda. From hints Gerda has let fall over the years, the child Rella has become obsessed with the notion that the noble Wallenberg is not only her true father but still alive. That dream gives her the strength to endure her mother’s contempt.

The novel is recounted in loosely alternating chapters by Gerda and Hanno Baum, now named Jack as befits his present humble role as a baker of coarse rolls. When we first encounter Jack, he is impersonating Hitler on Halloween, an act resulting in his being carted away to a mental hospital. There, shock treatments resign him to his subsequent life in the bialy factory. Once back home in his white tower room, he restrains his masquerading instincts and consoles himself by talking to trees, with which he feels a deep spiritual kinship ( Baum meaning “tree” in German). These conditions established, the story begins in earnest, dodging back and forth between Vienna, Budapest and New York, the war forcing these tangential lives into unlikely juxtaposition.

Because Jack is a pastry chef, the text is loaded with references to elaborate Continental desserts, all described in cloying detail. These desserts with their cream, butter, sugar, chocolate and meringue are made to bear enormous symbolic weight. Jack bakes them, the anorexic Rella gradually learns to eat them, the luscious Gerda gorges herself on his offerings. Virtually every metaphor is drawn from the pastry kitchen; analogies are relentlessly driven home by allusions to ovens and related objects.

Eventually this heavy batter must be baked into a denouement. In the bizarre and implausible finale, Gerda becomes involved in the heroin trade, a venture with predictably tragic consequences for the ill-fated Rella, who has just begun to bloom. Her decayed teeth have at last been replaced, her scrawny frame filled out with Jack’s magnificent pastries, the stringy hair cut, bleached and curled. Rella meets her gruesome fate looking better than ever before, a particularly macabre touch.

Contrived and overwrought, “Safe Houses” still demonstrates uncommon literary ability. Unlike most first novelists, who need to stretch into larger subjects, Alexander needs to reverse the procedure--concentrating upon more manageable themes, pruning her metaphors, restraining rampaging coincidence. “Safe Houses” is a profligate book, a showcase for all the author’s wares; as grandiose in concept as the “Rehrucken” she describes, the fancy Austrian cake baked and decorated to resemble a saddle of venison. Underneath the tormented shape and elaborate icing is a culinary staple.

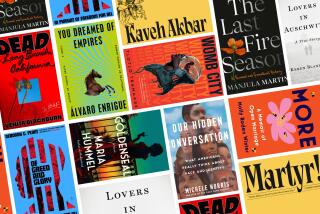

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.