The Black Pioneers : They Changed League for Good; Now NBA Has Forgotten Lloyd, Cooper and Clifton

- Share via

I can be in an airport--and I got no problem with not being recognized--but they don’t know me. Ran into the Pacers. They were polite and it’s not their fault they don’t know me. They’re young. But they should know, must know. They were bought and paid for by some people. --Earl Lloyd, first black to play in the National Basketball Assn.

The integration of professional basketball has come, like all other integration, at a frightful expense. But in the National Basketball Assn., where it seems most complete, the men who paid the most are largely forgotten and badly compensated, the game’s considerable debt to them apparently written off.

Consider that of the three men to break the color line in 1950, one has passed so unheralded that his death may yet be unreported in some parts. Another, his whereabouts unknown even to the team for which he once played and coached, counsels quietly in a big-city school district. A third, perhaps the best of them, drives a cab.

Yet their legacy is profound. Today, easily three-quarters of the players in the NBA are black. The players are now paid vast sums, and in accordance with their skills, not the color of their skin. Black men coach and attain front-office jobs. Equality, in many of the important aspects, has finally been achieved.

“And you know what I am, after all that?” asks Earl Lloyd, one of the men responsible for that equality. “I’m the answer to a trivia question: Who was the first black to actually play in the NBA? Through a scheduling quirk, I beat Chuck Cooper by a day, even though he was the first drafted and signed. You can win money on that one.” He laughs

It may be difficult now, having experienced a civil rights movement and seen the comparatively rapid reform in race relations, to imagine what it was like in 1950, when the black man first tried to play in the NBA. By then, it is true, Jackie Robinson had broken through to the major leagues in baseball, establishing an inevitability of integration in other sports. Still, that inevitability was small comfort to a black man who walked into a gym of 10,000 white fans, escorted uncomfortably by white teammates. The word “nigger” somehow resounded oh so distinctly above the crowd noise.

Lloyd, who along with Chuck Cooper and Nat (Sweetwater) Clifton, was the first to brave the unknown, admits to all the little injustices, all turned into cliches over the years. “It was all the things you hear,” he says. “You couldn’t stay at certain hotels, eat at certain restaurants. You took your chances on the streets in some towns. Remember, these were the 50s. When we played towns like Paducah, Ky., or Ft. Wayne--well, I wasn’t there by choice.”

Lloyd has vanished from sight as far as the NBA or even his old team, the Detroit Pistons, are concerned. He now works in a youth program that prepares students for employment in Detroit. He seems to have distanced himself from the days when he had to cower in his hotel room and take room service alone. But he remembers.

“Most of it was just isolated instances,” he says. “And it’s hard to be bitter about something that happened all the time. We more or less took it in stride. One year, my second year when I was with the Syracuse Nationals, before we opened in Baltimore, we played an exhibition in South Carolina. I was left behind. I can look back now and say you shouldn’t schedule a game where one of your players can’t play. I can say the players should have stood up for me. But it was different then and I could hardly be bitter. I didn’t appreciate it, I will say that. But I wasn’t bitter then, and I’m not now.”

The black pioneers, to a man, startle by their lack of bitterness. Sweetwater Clifton, who was drafted by the New York Knicks that same historic year, almost apologizes on the fans’ and owners’ behalf. “It was different,” says Clifton, who drives a cab in Chicago after a 10-year career in the NBA. “I had been playing with the Globetrotters, to white crowds, but when you walked in with an all-white team, well, it was different.”

Clifton, when pressed, can recall a few race-related incidents. No, he didn’t always stay with the team, but he didn’t make anything of that. “I knew all the hotels in all the cities from my days with the Globetrotters,” he says. “Some cities I had no problem staying with the team. All over New York, Boston--I had no problem. Other towns, I just moved on over to another hotel. I had more fun that way.

“It was no problem, really. At that time I had no time to be bothered. I had a place to stay and most times friends were looking for me. Life was going too fast to think about racism.”

There was, however, one semi-legendary incident involving Clifton. Once in an exhibition game with the Celtics, Clifton threw a dazzling pass by Bob Harrison. Clifton had been a Globetrotter, remember. “He said, ‘No nigger do that to me,’ ” recalls Clifton with a chuckle. “It was a one-lick fight. I was lucky enough to knock him out.”

That KO, among the three blacks in the league, was a satisfying amusement for years. Lloyd tells the story differently but with the same glee. “Way I heard it,” he says, “Sweets just turned and clenched those two meathooks of his and you could smell burning rubber for miles. Sweets was 6-7, about 230 pounds. Never mind being broad-minded, just think some small intelligence. Why call Sweets anything. It could be detrimental to your health.”

Chuck Cooper, in an account he provided Art Rust’s Illustrated History of the Black Athlete before he died two years ago, claims a fight for himself, though not a one-punch knockout. “I had only one fight in the NBA that was clearly over race,” he recalled in the book. “That one fight was against the Tri-Cities Blackhawks. After fighting for a loose ball, a player said, ‘You black bastard.’ Not looking for a fight, I gave him a chance to back down by asking him not to say that again. He looked me dead in the eye and said it again. So I took my open hand and shoved it as hard as I could into his face.”

A brawl broke out between the Celtics and Blackhawks, bitter rivals anyway, but Cooper was later acquitted of any wrong doing when the commissioner heard the whole story.

But racism mostly worked in silent and less visible ways. It was more than hearing “nigger” or being refused service. Cooper, in his account for Art Rust, said: “There were things I had to adapt to throughout my career that I wouldn’t have had to if I were white. I was expected to play good, sound intensified defense and really get under the board for the heavy dirty work. Yet I never received the frills or extra pay of white players.

“I remember Sweetwater Clifton, the first black on the Knicks, was told to play less of his game.”

Yes, there was something to that, Clifton says. “I realized that, being the first black, I couldn’t do anything people’d notice. So I had to play their type of game--straight, nothing fancy. No back-hand passes. It kept me from doing things people might enjoy. My job was to play the toughest guy and get rebounds and not do too much throwing.

“The fans that saw me play before with the Globetrotters wondered why I didn’t do more. My teammates used to say, don’t play Globetrotter style. So I didn’t do certain things, didn’t play my game. They missed out. I missed out.”

Clifton doesn’t make too much of this either. “I had been in the Army, you know, and I was a disciplined, quiet kind of guy,” he explains. “I was used to following orders. I suppose it was why I was chosen to play in the NBA because there certainly were blacks better than me. Marques Haynes--how could he not be in the NBA?”

Looking back it is possible to say these pioneers went along, got along. But there is no way to know the grinding effect of racism, which is what prepared them for the NBA. Cooper, who played basketball at Duquesne, after all saw a college game flat-out canceled at the last minute when Tennessee learned of his presence. Tennessee refused to come out onto the floor if he was allowed to play. Duquesne did not back down.

Mostly, though, life was a process of backing down, accepting one inequality after another to achieve even a little equality somewhere down the line. It is against this background that the smallest gestures loom heroic.

“Once in St. Louis, I walked across the street to join my teammates at a coffee shop,” Lloyd recalls. “Their food was practically on the table when I was told I wouldn’t be served. They got up and left.

“Something else that impressed me. Hotel in Ft. Wayne said I could stay there but I couldn’t eat in the hotel restaurant. Now what can I do? Am I going to go out looking for a restaurant that will serve me? Not likely if the hotel that’s keeping me won’t serve me. You understand? Room service was all I could have.

“My coach at the time, Bones McKinney, who was described by folks other than me as redneck, came to my room and ate with me that night. Doesn’t sound like much, but in 1950. . . . “

And then there was the matter of pay. Clifton learned about that inequality first hand in his dealings with the Globetrotters of all teams. “We played an all-star game my last year (1949) against a team Bob Cousy was on. After the game, Cousy, who got to be a pretty good friend, asked what Abe Saperstein paid us. He showed me his check for $3,000. I was ashamed to show him mine. It was for $500.”

Of course, by then, Clifton had somewhere else to go.

“It was probably amazing that the color line was broken as soon as it was,” says Richard Lapchick, who directs the Center for the Study of Sports in Society at Northeastern University and who observed the integration first hand as the son of the man who signed Clifton. “The world still hadn’t changed that much by 1950. The blacks had come back from the war and found a country where an anti-lynching bill still couldn’t get through congress.”

Still, Lapchick says, there was no doubt that the NBA would soon be integrated. In fact, there was a meeting in 1948 to consider the addition to the NBA of the Rens, an all-black barnstorming team which was arguably the best team during the 30s. “My father (Joe Lapchick), who had played against the Rens, convinced the league to give them a hearing,” Lapchick says. “It seemed a good possibility because they were bringing teams in that represented large black populations. He brought in Bobby Douglas, the founder of the Rens, and he made a presentation. The owners got up and said they didn’t need the Rens and that was that.”

The problem, Lapchick says, is that, “they just weren’t sure what would happen. It wasn’t like in baseball. The dominance of the Negro leagues in baseball was much greater than it was in basketball, which really just had two teams, the Harlem Globetrotters and the Rens.”

Another problem, incredibly, was one of those black teams, the Globetrotters, who would definitely not benefit by integration. In the early NBA days, the Globetrotters would bring their act to the NBA franchise and build the gate with a double-header. It was not money the NBA teams could afford to lose, which they certainly would if the NBA was integrated. In fact, when the Celtics did finally draft a black player, the Globetrotters struck Boston from its list of destinations, at some cost to the Celtics.

But by 1950 some owners and coaches began to recognize, however slowly, what might be called the competitive imperative. That is best summed up by Walter Brown, the Celtic founder. When he announced that his team had selected Charles Cooper in the second round, the closed door meeting in Chicago fell mute. “Walter,” said another owner, “don’t you know he’s a colored boy?”

Brown’s famous rejoinder: “I don’t care if he’s striped, plaid or polka dot, so long as he can play.”

The Knicks followed by buying Clifton’s contract from the Globetrotters and the Washington Capitols followed by drafting Lloyd out of West Virginia State.

For such an important breakthrough, it was still many years before the number of blacks in the league grew. “In 1954, there were four black guys in the league,” Lloyd says. “That went to maybe seven in 1957.”

Adds Bill Russell, who joined the league in 1956: “I’ll just tell you this, the first championship the Celtics won in 1957, I was the only black player on either team to play for it.”

Even when teams began drafting black players in numbers, it was still years until they would play them in numbers. It was Russell who famously identified the NBA quota system. “The general rule,” he once said, “is you’re allowed to play two blacks at home, three on the road and five when you’re behind.”

UCLA Coach Walt Hazzard, who played for several NBA teams in the ‘60s, says the number of blacks per team was pretty much held to three. “It was unstated,” he says. “Nobody had more than three until the emergence of the American Basketball Assn. Then the owners were forced to go after talent, not color.”

Lloyd says the eventual equality in the NBA was really assured when major colleges began letting blacks into their programs. “How could you deny blacks to the NBA when major universities are taking black kids. Who’s going to draft and leave Kareem Abdul-Jabbar sitting there. Nobody’s crazy. When you get Bill Russell, you can justify playing blacks in the NBA.”

But in the meantime, NBA owners were wary of antagonizing the white fans, who, they assumed, wanted to see as many white players as possible. “It was the old adage that you needed a white star to attract fans,” Lloyd says.

But this, too, was eventually disproved. “I really believe this,” says Lloyd. “They’ll come to see you if you’re winning, and you could be putting gorillas on the floor. Losing? Then you might have a problem.”

The Boston Celtics, largely under the guidance of Red Auerbach, was the team to disprove this adage, not so much by drafting Cooper, but by playing as many four blacks at a time in the ‘50s. “What Red did basically was get the best people for the job, period,” Russell says. “He might have ended up with an all-white team, or an all-black team. Gorillas would be especially good, because he wouldn’t have to pay them but bananas. Is the team any good? That’s what it’s all about for Red.”

One wonders why the Celtics stood out in this respect for so many years. To which Russell says, “One wonders why we won all those (11-of-13) championships.”

Russell, though he came late to the NBA, was a pioneer in his own way. He was the first black superstar in the league and he correctly gauged that, as a superstar of any color, he had some leverage. “In 1961, in an exhibition in Lexington, the black players could not get served at a restaurant,” he remembers. “The black players left, didn’t play that night. Best thing could have happened.”

Why? “Well, let’s just say that without us, it was a different game. We never ran into that again.”

Another pioneer, in another way, was Wilt Chamberlain. “Keep in mind that there are some weird ways to express racism,” Russell says. “The blacks never got a fair hand until Wilt came along. I’m talking about being under-paid, never getting endorsements and weird things like not getting cars. The white players often were given cars, for advertising reasons. The black players got discounts. But Wilt, I have to give him credit. He was the first to have leverage and the first to exercise it. Whether he was threatening to box professionally or play tight end for the Kansas City Chiefs--he was getting his money, I guarantee that.”

Russell, who was the first black coach--for Auerbach of course--still does not see integration in the NBA as complete. Front offices are largely white, for one thing and there are more marginal white players than marginal black players.

Lapchick, who has researched the subject, confirms that. “The league is 75% black, yet front offices are just 5.6% black.” And, he says, the lingering suspicion that marginal white players are retained in favor of marginal black players has some statistical basis. “The scoring average for black athletes was about 2% higher than for whites,” he says, indicating that a black player still has to be better to be equal.

But, as Russell says, “If we didn’t have that to change, we wouldn’t have anything to do.”

It almost seems that when the NBA was integrated there was a kind of grandfather clause for the first blacks: they could always be discriminated against, regardless of reform.

Cooper told Art Rust, “Another thing I’m somewhat resentful about is that at the time, I would have liked to get into coaching. I felt I knew the game and how to handle young men. But there were no opportunities for black coaches then. I got one offer from a school in Piney Woods, Miss., but they were still killing black people down there then. So I declined.”

Lloyd, who did coach briefly with the Pistons, found a similar problem. He was invited to interview for a head coaching job at Wisconsin and was asked such questions as what kind of “balance” he’d have on his team. He didn’t get that job.

And Clifton? It is interesting to look at a roster of a team he played on. “It’s a very tough situation for Nat,” Lapchick says. “He has to know that all his teammates, all the guys that started with him, have been wildly successful. Vince Boryla is vice president with the Denver Nuggets, Ernie Vandeweghe is a doctor, Carl Braun a stockbroker, Dick McGuire’s still with the Knicks. Nat never got those opportunities, which is one of the enduring aspects of racism in sports.”

But the pioneers reflect no bitterness and claim little achievement, which would prove how special they are. Chuck Cooper presumably rests in peace, never having taken, or gotten, credit for what he had done. Earl Lloyd, the answer to a trivia question, secures employment for underprivileged kids who have never held jobs. “I sleep good at night,” he says.

In Chicago, a man asks a black cab driver, a man in his 40s, if he knows a fellow cab driver, a man named Sweetwater Clifton. The cab driver remembers, if so many others don’t. “Yes,” he says slowly. “But he’s Mr. Clifton to me.”

More to Read

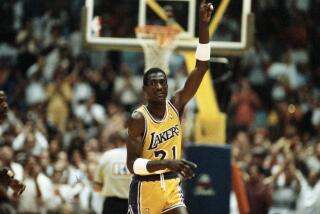

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.