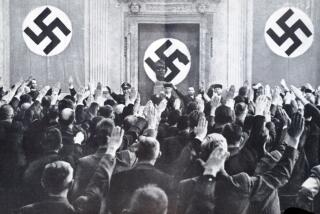

The Last Nazi : THE LIFE AND TIMES OF DR. JOSEPH MENGELE by Gerald Astor (Donald I. Fine: $18.95; 305 pp., illustrated)

- Share via

In a telling phrase, written in 1953, the English historian Gerald Reitlinger described Heinrich Himmler’s background as “depressingly normal.”

Why “depressingly”? Because presumably we should prefer to see a list of huge traumas peppering the background of the major Nazi war criminals, which might account for their subsequent aberrant behavior.

In Joseph Mengele we have another example of what Hannah Arendt once called the “banality” of those who committed crimes against humanity. Mengele was born into the most prominent family of the small town of Gunzburg, about half way between Stuttgart and Munich. There is nothing in his past to suggest that he would become the evil doctor who decided who was and who was not suitable for transfer to the gas ovens at Auschwitz, or that he would earn such nicknames as “Angel of Death,” “Angel of Extermination,” or quite simply, “The Butcher.”

According to Gerald Astor, Mengele “was not a TV type homicidal maniac who lived only for the pleasure of killing,” nor was he “even neurotically impaired by anxieties or phobias.” Further, there is “no indication of sexual problems . . . that would distinguish him from most normal men. . . .”

All of this is written quite unambiguously, and yet elsewhere in the very same book, we read: “internal sexual conflict, hatred of Jews, and obsession with controlling the inmate population combined in Mengele to assign especially harsh treatment for women unlucky enough to become pregnant. . . .”

Which evaluation is correct? And how can the author express such varying views as to what lay behind his subject’s actions?

For me the answer lies in the position within the book at which we read both extracts. The comments suggesting abnormality occur in the center of the book when the author has been describing events so fiendish that he feels driven to suggest causes. The extract suggesting Mengele’s normalcy occurs in the summing up section, at the end, when the author has had the opportunity of distancing himself from the subject.

I think it is important to keep stressing the normalcy of the major war criminals; this is the only way we can continue to be vigilant and look for potential outbreaks of the same syndrome. I shall therefore close with one of the better statements in the book: “Mengele was part of the mainstream of his nation and its prevailing moods. . . .”

Exactly.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.