Whittier College Rock Makes Truly Colorful Pet

- Share via

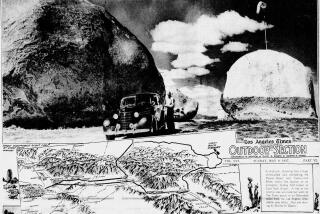

The “rock.”

Alumni always ask about it.

Students pet it for good luck.

And during January and early February, when fraternal societies pledge new members at Whittier College, it changes colors more often than a chameleon. Student pledges paint it sometimes four or five times a day.

“It gets so busy,” said Susan Harvey, the college’s director of alumni relations, “that societies have to make rock reservations.”

The rock is an institution on the Whittier campus. Few landmarks or personalities at the Quaker college, founded in 1887, are more recognizable or remembered. Even the president of the liberal arts school knows his administration is only as solid as the rock, a granite boulder set in the center of campus.

“If it was to disappear tomorrow,” Eugene S. Mills said recently, a thin grin belying his presidential tone, “I’m not sure I could survive the fallout.”

Rest assured that Mills has much more on his mind than the security of the rock. But Mills admits he would be among the first to hear from students, staff and alumni if the rock were missing.

Through the years, the rock has been decorated like a Christmas tree and a snowman. One society periodically plasters it with concrete and then covers it with beer cans. Phantom painters deliver birthday messages and announce parties on the rock’s weathered surface.

One group even advertised its fall dance, the “Fowl Ball,” by coating the rock with pillow feathers.

Legend has it that the rock has even been the target of takeovers by rival colleges.

“The rock has assumed mythic proportions,” said Chuck Elliott, a free-lance writer who is completing a 240-page history of the college for its centennial celebration next year. “Buildings have come and gone, but the rock is still here, a symbol of permanence.”

In recent years, however, several alumni have voiced concerns that the rock is “shrinking away to a pebble,” Harvey said.

Years of paint, plaster and pranks, the worried alumni contend, have left the rock half the size it was in 1912 when three students carried the boulder by horse and buggy to campus.

Photographs from that period show that the rock was about shoulder height when students stood next to it. It weighed about two tons.

Today, it is about waist high and it is no longer the imposing piece of gray-flecked granite it once was.

The state of the rock prompted action several years ago from the administration, which is ever mindful of the value of happy alumni to a private college dependent on contributions.

To prevent further cracking and chipping, the practice of dousing it with a flammable liquid to burn the paint off has been abolished.

Campus officials also require the Franklin Society, a male fraternity, to cover the rock with a plastic sheet before coating it with concrete and attaching beer cans, a semi-annual rite by the group.

There has even been talk, Harvey said, of encasing the rock in a thick transparent plastic and then setting a blackboard next to it for messages.

Fraternal Societies

Among campus groups, the fraternal societies are most closely tied to the rock. About 20% of the student body or roughly 200 undergraduates belong to one of the five female or four male societies.

Societies are Whittier College’s version of fraternities and sororities. Unlike other universities and colleges, where fraternal groups are affiliated with well-financed national organizations, founders of Whittier societies chose to be independent of national groups that could set up discriminatory rules for membership.

The rock plays a significant role during society pledging. Female pledges, in particular, must paint the rock several times a day in the society’s colors to prove loyalty to the group.

The rock was a gift from the class of 1912, which wanted to leave the campus a “lasting gift,” Elliott said.

Despite several attempts to steal the rock, it was missing only once.

One morning in the early 1970s, Harvey recalled, officials arrived at campus and discovered a big hole where the rock had been and a huge pile of dirt next it. For several days, authorities searched for clues, but were unable to find the culprits or the rock. The disappearance made local headlines, and Harvey remembered “a lot of long faces” on campus.

“Then came the decision to fill the hole,” she said. “And lo and behold as they began to shovel the adjacent pile of dirt, they found the rock underneath.”

In his travels to raise funds, President Mills said the rock is often the first thing alumni ask about.

“They always want to know if it’s still there,” he said. “because it holds so many memories for them. Honestly, I don’t know what I’d do if one day the rock was gone.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.