COLLEGE NOTEBOOK : Swimmers Reach Razor’s Edge a Day Before Meet

- Share via

Early next Wednesday, maids will enter the rooms at the Radisson Inn in Orlando, Fla., and commence cleaning. In most of the bathtubs they will find the usual assortment of soaps, shampoos and hair conditioners. But in a couple of rooms, those occupied by the Cal State Northridge women swimmers, the maids might find other things--like clogged drains filled with giant masses of hair.

As they head into the NCAA Division II championships next week, both the women and men--who have piled up 16 NCAA team championships in the past 13 years--will perform one of the strangest rituals in sport. They will take out cans of shaving cream and packages of disposable razors and proceed to slice away at their limbs, shaving off everything that has grown since December, when they last shaved.

They have all gone without shaving for the past eight weeks to maximize the change from hairy to hairless, giving themselves the feeling of having the slickest, smoothest bodies possible as they head into the only meet on their schedule that really matters.

For the men the shaving will mean the beginning of strange days, because when the NCAA meet ends, they will still have no hair on their arms or legs. The 15 talented male swimmers on one of the finest Division II teams in the United States will, for several weeks, appear to be contestants in a female impersonator contest.

But for the women, the shaving will mean a return to normalcy. For two months their legs have gone unshaved. At a final practice session Thursday on the CSUN campus, the parade of women emerging from the locker room could easily have been mistaken for an East German women’s track team. Or an East German beauty pageant, for that matter.

“It’s gross,” said Tina Schnare, a freshman ranked No. 1 in Division II in the 100-meter breaststroke, who has been spared much of the embarrassment by having the good fortune to grow blond, nearly invisible hair on her legs.

“A guy was walking by one of the other girls on campus last week and I heard him say, ‘That’s sick. I should buy her some razors.’ That’s what we have to put up with. You hear things all the time.”

Come on, now. What things? You mean little innocuous quips like, “There’s less hair on my car’s sheepskin seat covers?” Or “Hey, you got feet at the end of those legs, or paws?”

Shaving the body hair is almost mandatory among top-level swimmers. Some say it actually makes them glide more easily through the water, that any hair at all creates drag in the pool. But the real reason for the male and female shaving rituals is far more psychological than physical.

“I guess we all know that it’s mental,” Schnare said. “But the mental part is so important right now.”

Coach Pete Accardy says he can’t remember the last time he saw a swimmer in a national meet enter the pool with any visible body hair.

“It gives the swimmer a completely different feeling,” he said, “a feeling of weightlessness. You almost can’t feel your arms or legs. Hair follicles transmit the sensation of the moving water. When you get rid of all the hair, you feel so much stronger and smoother. It’s a strange feeling.

“But most of it is in the mind.”

Wrong, Pete. Most of it is in the drain.

The women will hold shaving parties at the hotel the night before the meet begins. They laugh, tell each other their legs look a lot like Steve Garvey’s forearms and go about the business of shearing their way to skin.

“After not having shaved for so long, first we have to start with things like barber’s clippers,” said Jude Kylander, a Pennsylvania import who has been going through the ritual since ninth grade. “We pile into the bathrooms with a lot of razors and go at it.”

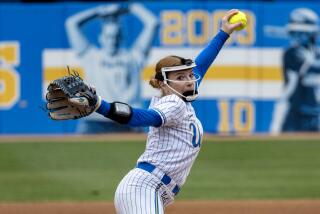

When CSUN’s Kathy Slaten began complaining of pain in her pitching hand recently, a lot of people were concerned. After several examinations, doctors found the problem. And the problem, while certainly not funny to anyone except opposing batters, has a medical name that has to rank high on anybody’s “Why People Make Fun of Doctors” list:

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

It is a slight strain of ligaments and tendons caused by gripping the softball too tightly.

But what Carpal Tunnel Syndrome sounds like is a rare psychological problem found exclusively among fishermen--the unnatural fear of catching a carp too large to fit through New York’s Holland Tunnel.

Despite the problem, Slaten said she will continue pitching for CSUN, which begins its California Collegiate Athletic Assn. schedule Saturday with a game at home against Cal State Bakersfield.

The price is wrong: When Liz Enright found herself on the set of the TV game show “The Price Is Right,” she could hardly believe it. She and CSUN basketball teammate Denise Sitton had obtained tickets for the show and Enright was shocked when she was picked from the crowd to be a contestant.

When her TV hosts rolled out the first item, a gaudy backgammon table, Enright had the first guess at the price. She glanced at Sitton. Sitton glanced at the backgammon table and whispered, “$400.”

Enright figured that sounded about right, and that was her official guess. She was off by a mere $1,300.

“I was so nervous I didn’t even listen to them describing it. For all I knew it was made of gold,” Enright said.

End of Enright’s TV career.

“It looked like a piece of junk, to tell you the truth,” said Sitton, obviously confusing “The Price Is Right” with “To Tell the Truth.”

“Liz looked confused up there, so I thought I would help her out. We were both excited. I guess we blew it. It was kind of humiliating, but better her than me.”

Ah, isn’t nice to see that the old team spirit still lives?

The show, taped last October, finally aired last Wednesday night. Enright gathered friends and relatives around her TV set and awaited her moment of glory. Or moment of embarrassment.

She got neither. What she got was President Reagan, whose live speech on the national budget-balancing battle preempted Enright’s brief TV debut.

In two CSUN volleyball matches last week, the play-by-play announcer--had there been one--might have described the action like this: “No. 12, Ribarich, spikes the ball, but Ribarich, No. 12, digs it out and returns it for a point. Ribarich now serving, and he aces one past Ribarich.”

Who is this Ribarich fellow? Is he the victim of a split personality?

No, there are two Ribariches: John and Tom. John, a senior, plays for the University of Hawaii. Tom, a sophomore, plays for CSUN. In the two matches last week they wore the same number and played the same position. John (Hawaii) defeated Tom (CSUN) in both matches.

The Ribarich brothers played on the same high school team at Pacific Palisades. The used to practice against each other, separated only by the net. Now, they are separated by an ocean. But the rivalry lives.

“It makes me a little more relaxed,” said John. “I know I’ll always beat my younger brother.”

Watching the matches was their father, John Sr., who offered this explanation for having two standout volleyball-playing sons: “We clone ‘em.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.