Henry Aaron Finds a Niche All His Own

- Share via

If you were Henry Aaron, how would you like to be remembered?

It’s not that simple. On the face of it, you would say that Henry hit more home runs than any player in history. Ergo, he’s indelibly linked with this feat. You think of Henry Aaron, you think of home runs.

But, do you? Is Hank Aaron a metaphor for power hitting, overpowering excellence in any field? Do we say of a man “He’s the Henry Aaron of chefs,” for instance? Or do we still say of an outstanding performer “He’s the Babe Ruth of . . . “?

Face it. Even though Babe Ruth hit 46 fewer homers than Hank, he’s still the symbol of the home run hitter, not only to millions of American baseball fans but to other millions the world over who never heard of another baseball player.

Why is this? Racism?

I don’t think so.

You have to look at it this way: Babe Ruth was almost a cartoon character. He was this big, lovable, loud, uncomplicated Fred Flintstone of a man. He didn’t seem any more real than Mickey Mouse or Yogi Bear or Bugs Bunny or Santa Claus or John Wayne. It was almost as if he came walking right out of Disneyland. You didn’t know whether to ride him or pitch to him.

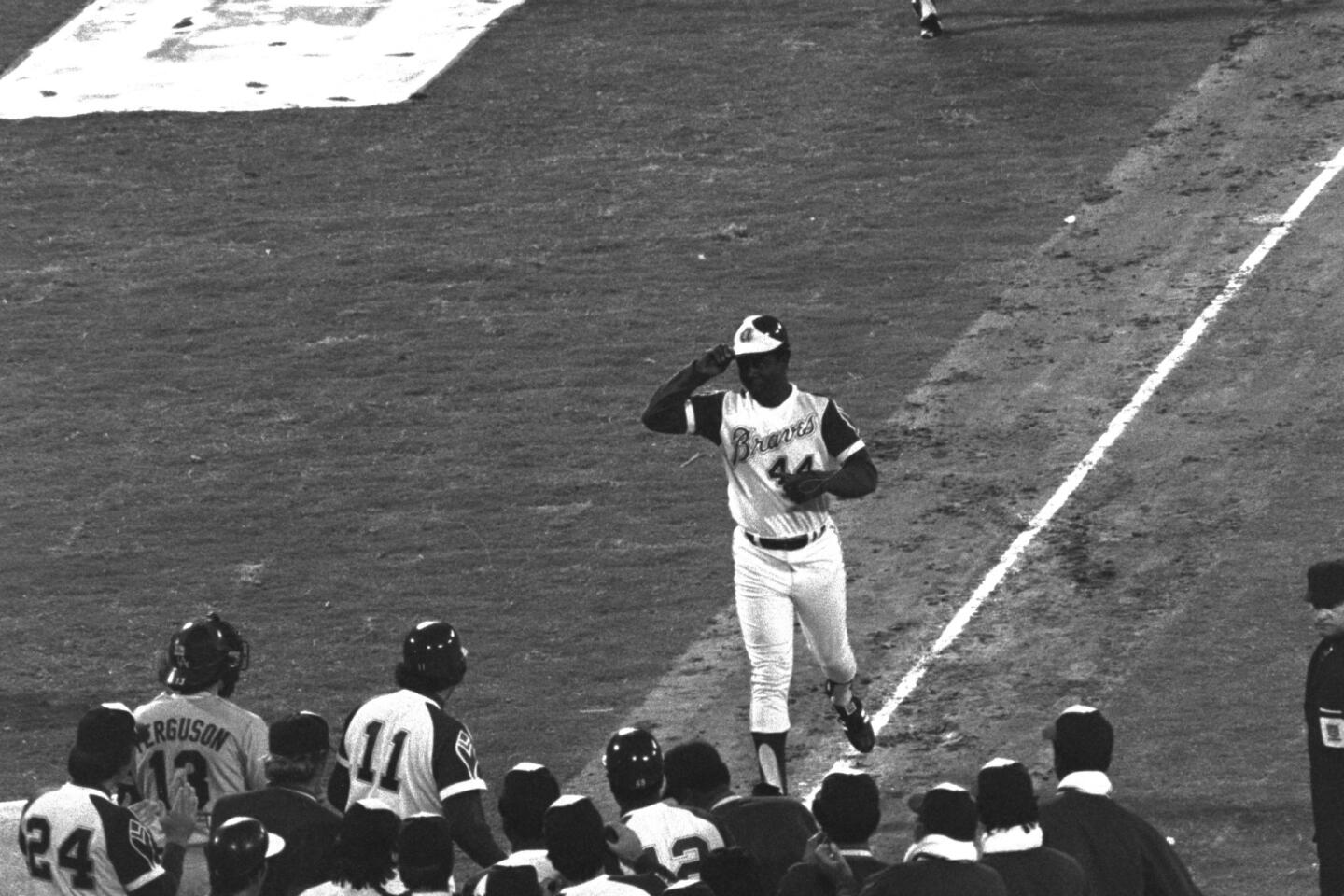

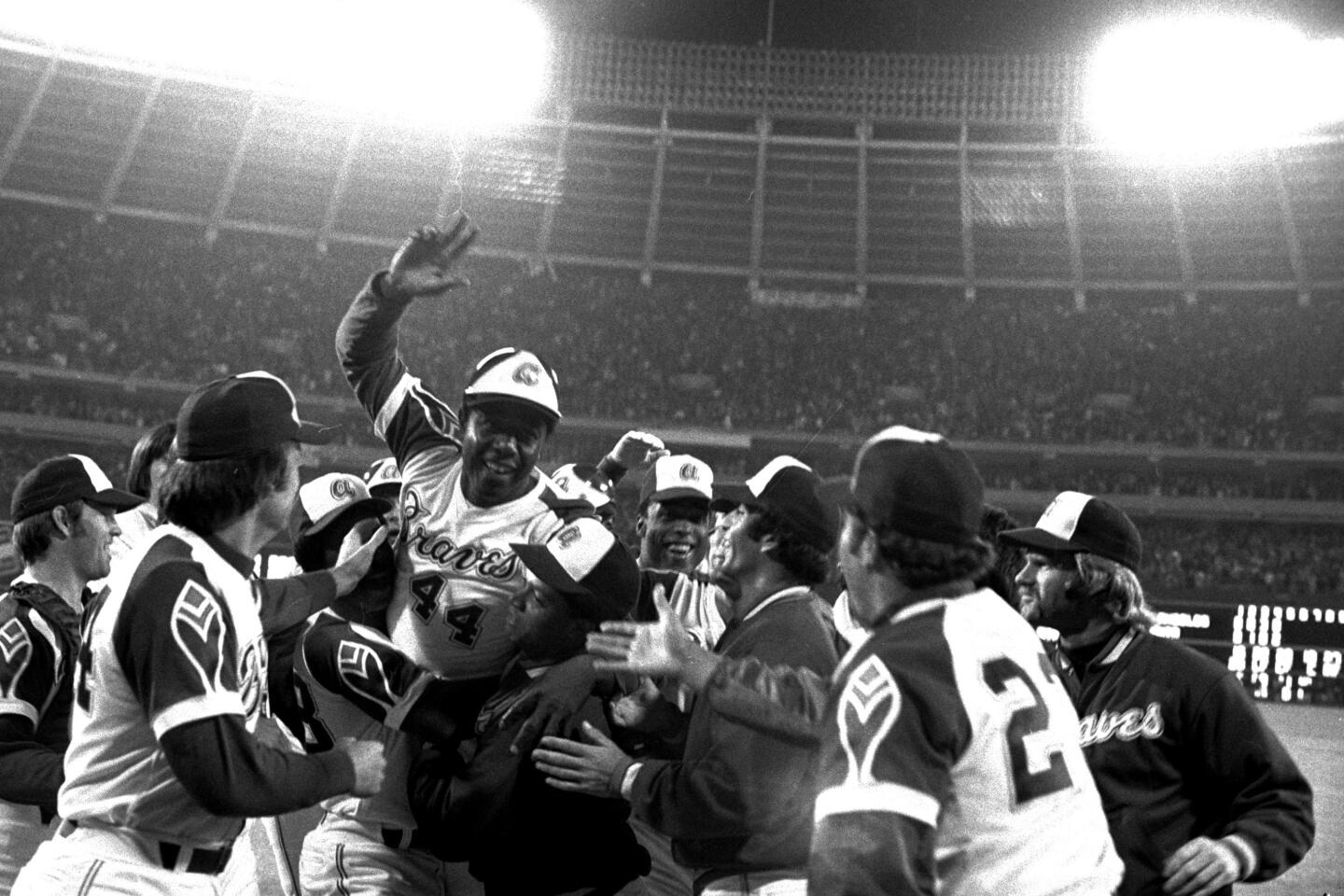

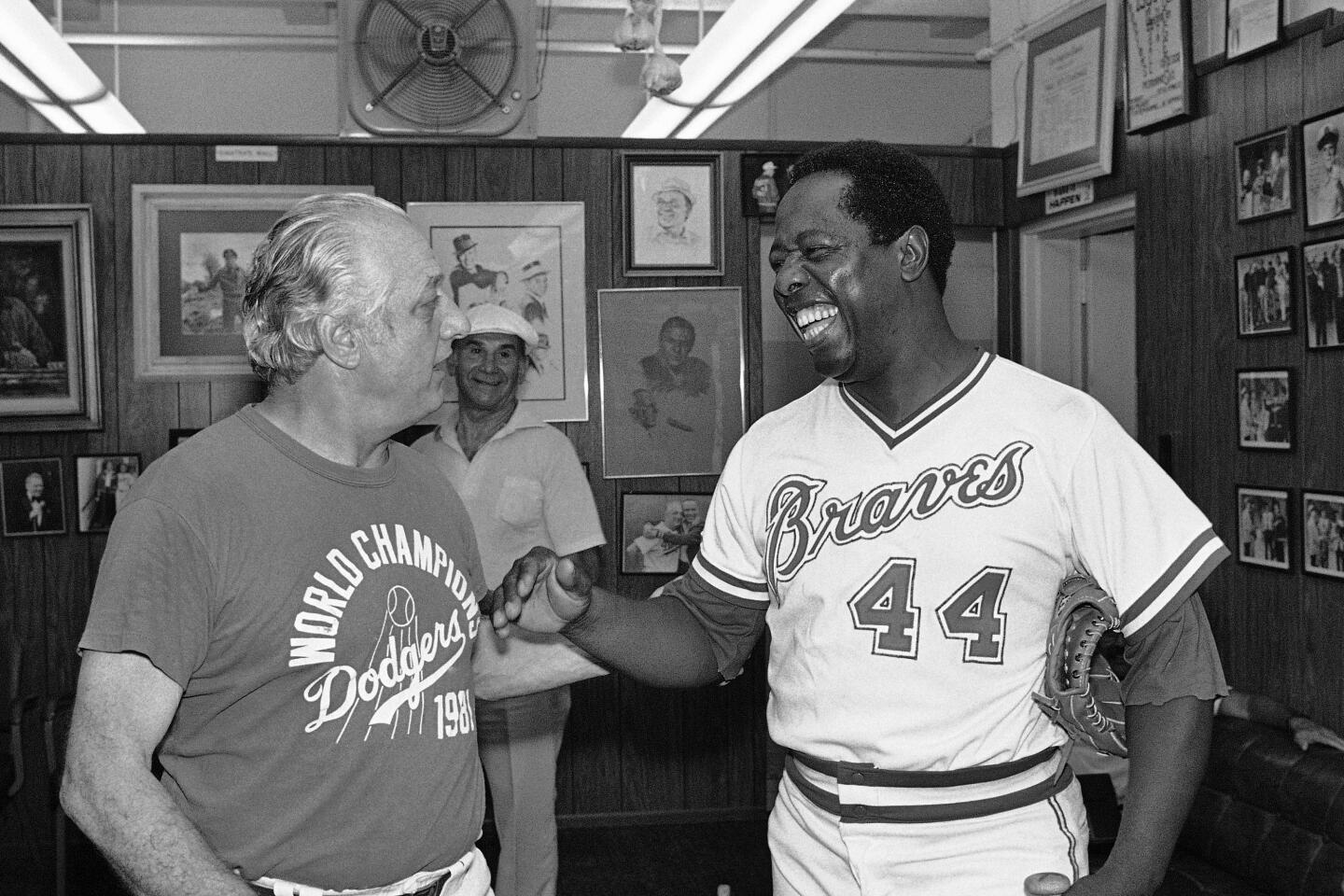

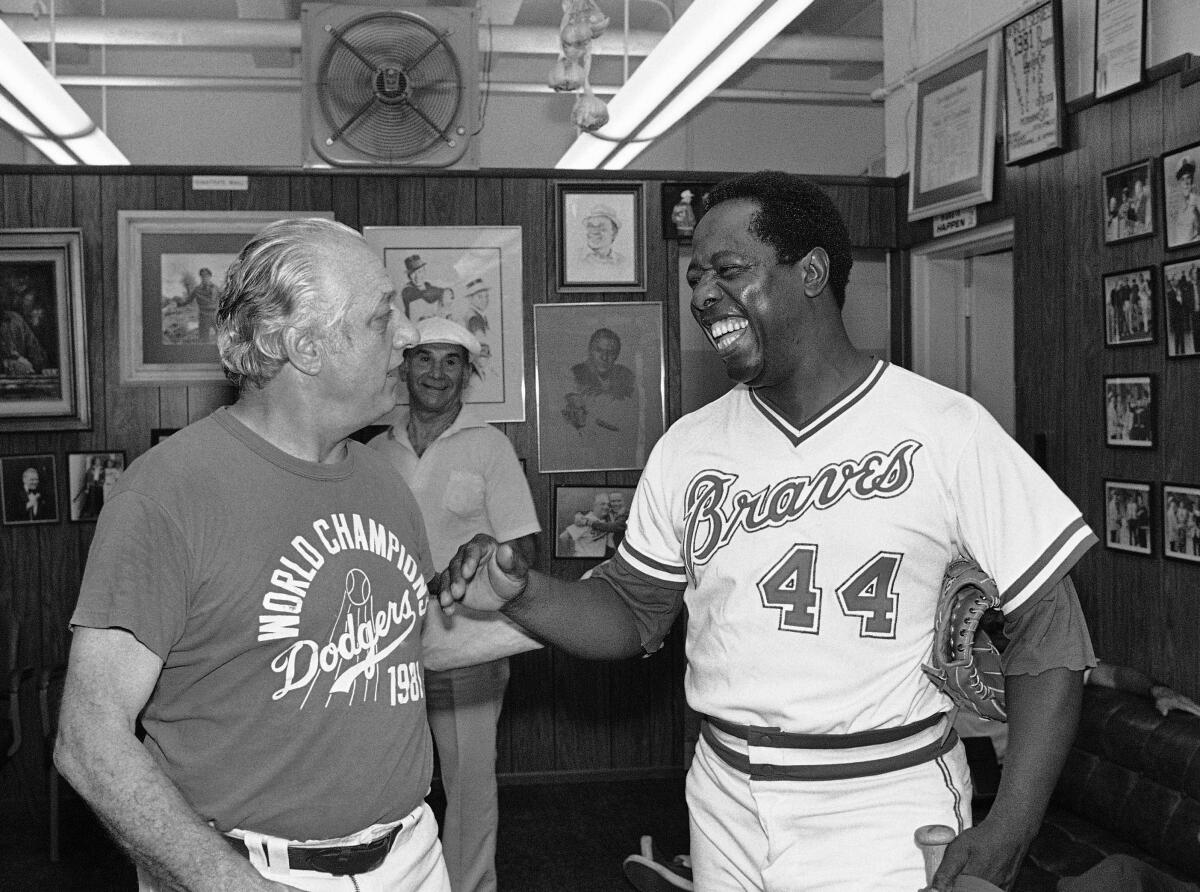

Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record in 1974 despite enduring racism and went on to hit 755 homers in a 23-year career.

Henry Aaron was more like a machine. He was quiet, self-contained, in control, efficient. He inspired more awe than affection. Henry was off nobody’s drawing board. Also, Henry did what he did outside New York. That’s never a good idea. Henry made the plays, too, but Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle and Duke Snider got the ink.

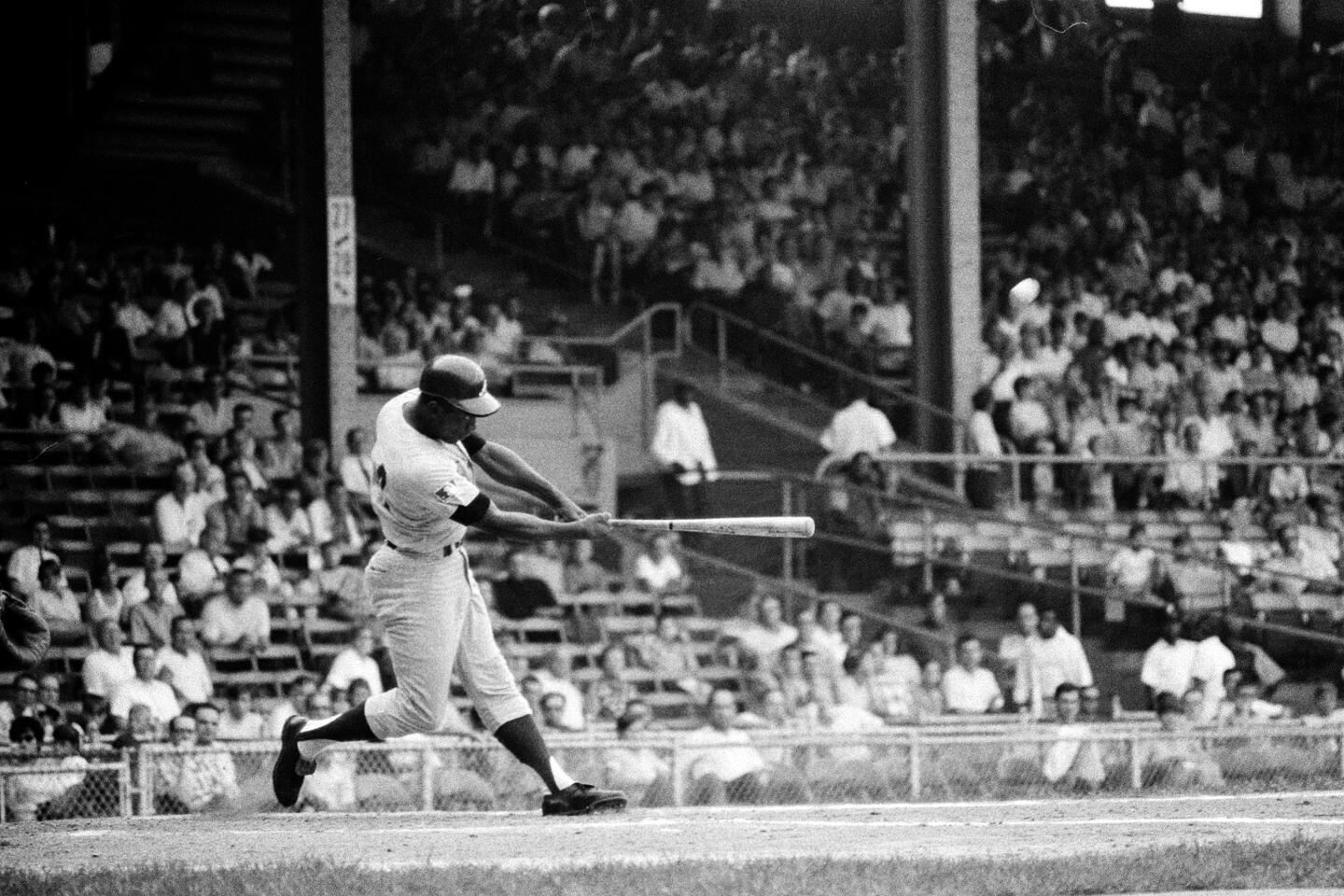

Henry may have been the best pure striker of the ball who ever lived. Rose and Cobb had the hits. But not the home runs. Ruth had the home runs. But not the hits.

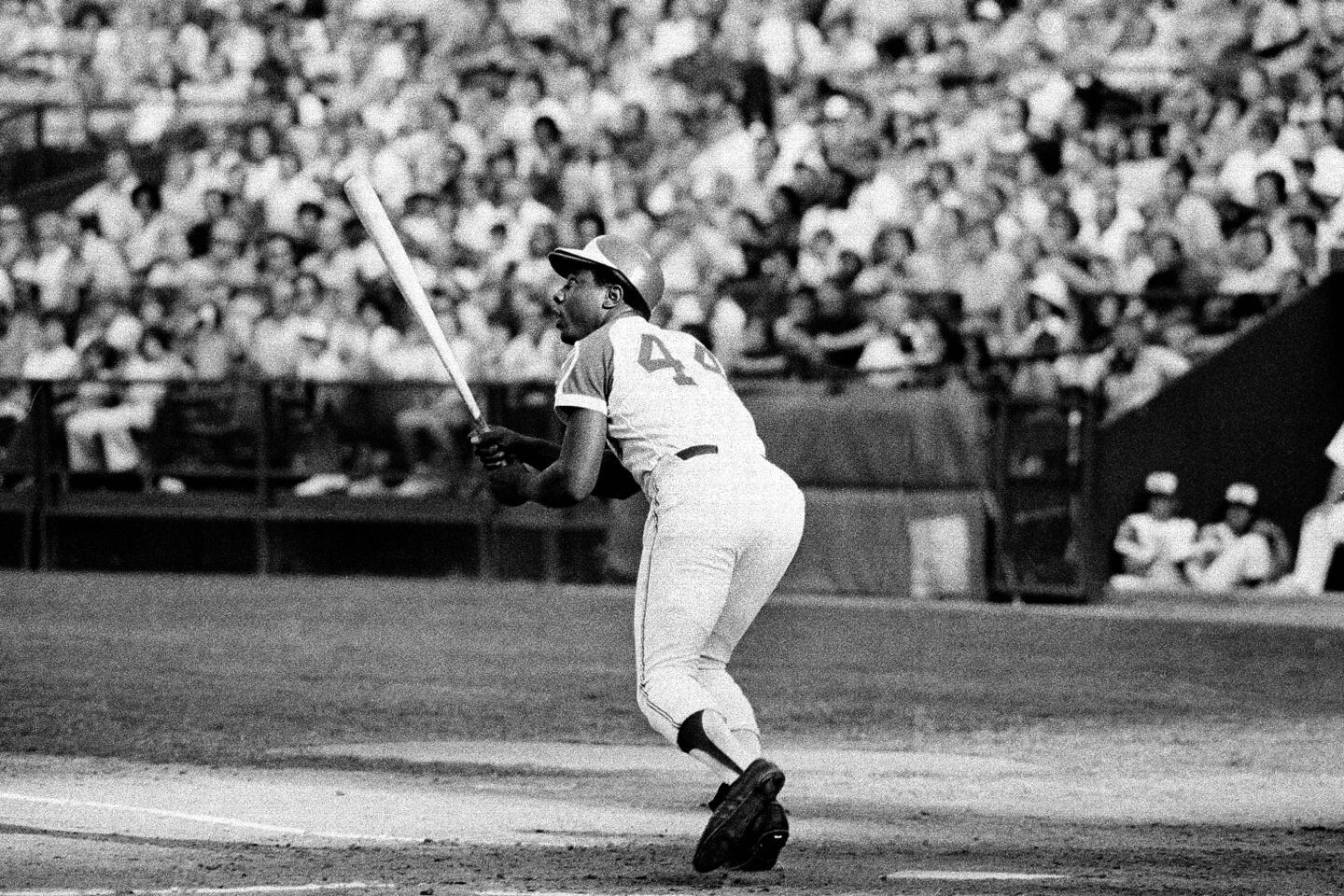

You see, Henry never even thought of himself as a home run hitter. He sort of crept up on the title. He even used to get annoyed in his younger days at being identified as a slugger. Henry thought he was far more than that. And he was.

He hit home runs almost as an afterthought. It’s possible Henry never tried to hit a home run in his entire career. Ruth seldom tried to hit anything but.

Henry was an all-around ballplayer. He could, as the locker room cliche has it, do it all. When he hung up his No. 44, whatever Henry didn’t lead the world in, he was second. Or at worst third. As the late Fresco Thompson used to say “Henry is a streak hitter, he only hits on days ending in Y.”

Henry led the game or was runner-up in so many categories, he almost fell between two chairs in baseball history. Henry had 3,771 hits — but that’s not 4,000. (Ruth never reached 3,000, ending his career with 2,873.) Henry had 755 home runs — but not 60 in a season, or even 50.

Henry was never flashy, just steady. Ironically, he was most like another great player — maybe the greatest — who also played in the shadow of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig. Like Gehrig, he was incredibly productive, dependable, impossible to get out in clutch situations. And, doubtless, one of the most admirable men ever to play the game.

But what does posterity do with him?

Unaccountably, a fast-food chain called, felicitously in this instance, Arby’s, has come up with a solution. They have chosen to identify Henry with that oft-overlooked but super-important phase of the game, the run-batted-in. They have linked Henry’s name — with baseball’s consent — in perpetuity with the Hank Aaron Trophy for annual leadership in RBIs, which just may be the most positive, productive stats in any score book.

RBIs are a measure of a ballplayer’s prowess that may supersede all others. And Henry’s 2,297 — Ruth is second with 2,204 — stand as a mark that will probably sit up there forever, like his 755 home runs or DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak.

“I don’t look for anybody to break it because nobody will play for 23 years day-in, day-out the way I did,” Henry observes. “With the money they’re making today, they won’t have to.”

Henry is pleased with the establishment of the Hank Aaron Trophy for the RBI leader annually because the sponsor awards $1,000 for every RBI posted by each league leader to the Big Brothers/Big Sisters of America. With the Phillies’ Mike Schmidt driving in 119 last year in the National League and the Indians’ Joe Carter driving in 121, the program is enriched by $240,000.

Henry is pleased with the program — “Kids are our biggest problem at any time” — and pleased to find this niche for himself.

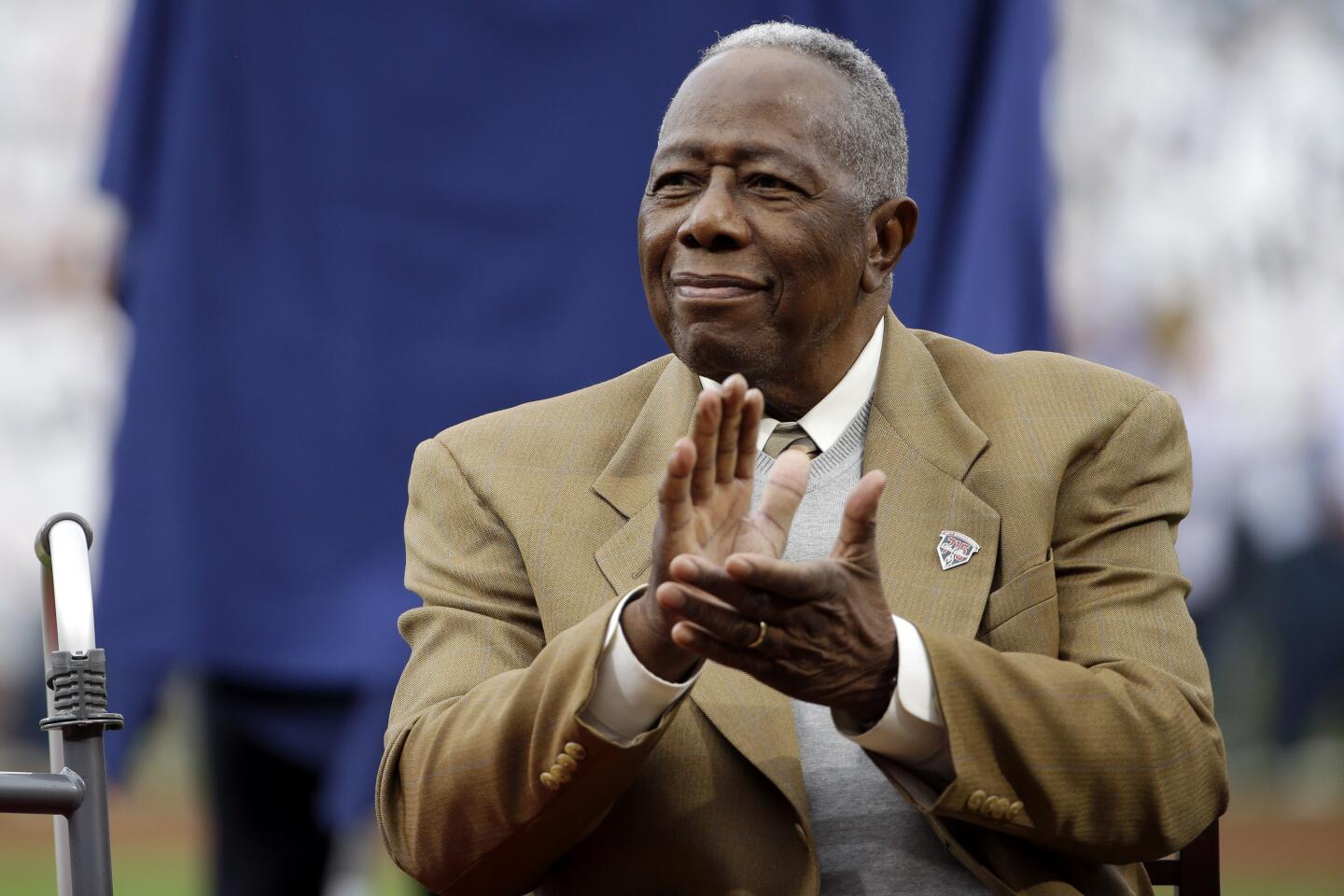

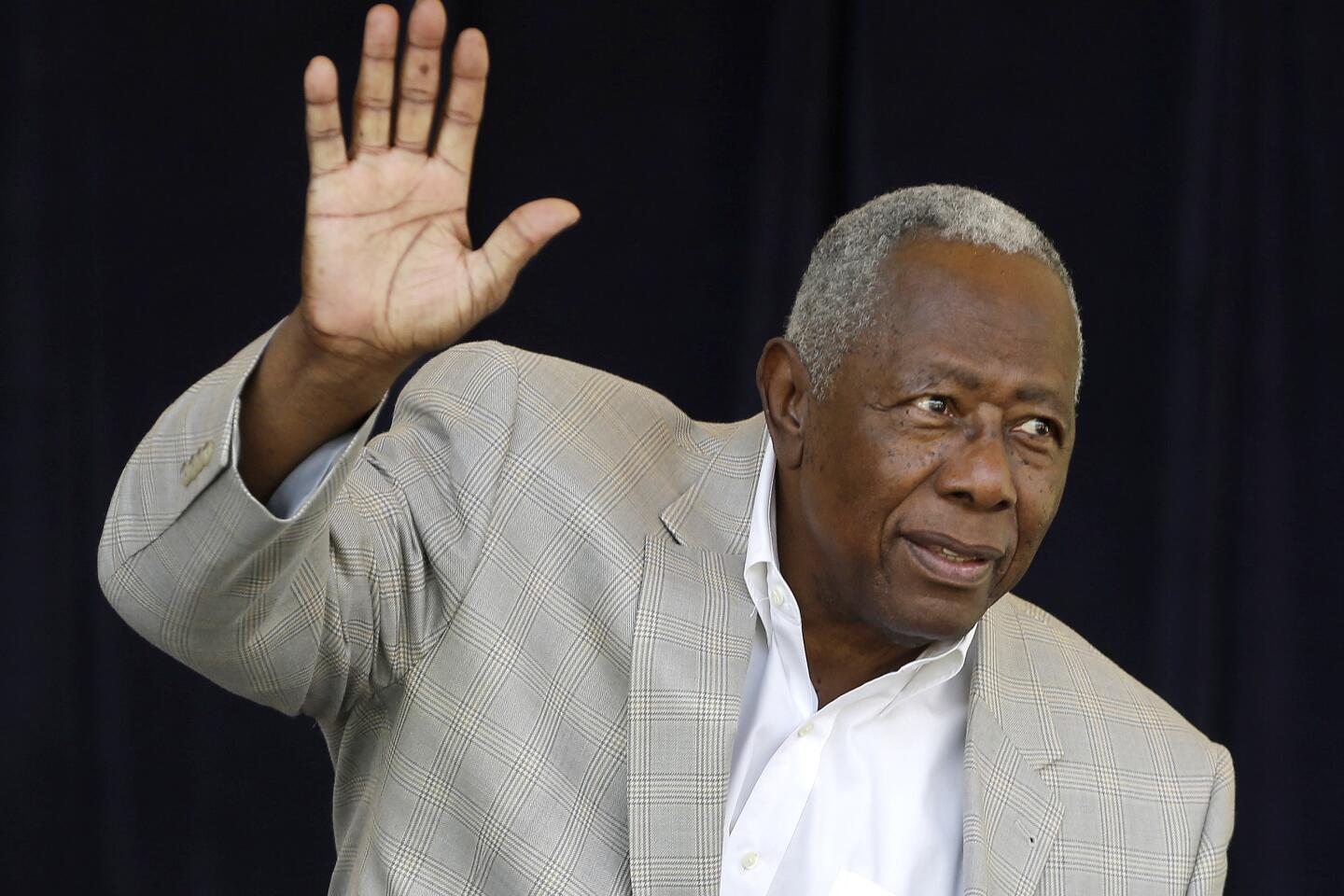

Barry Bonds, Magic Johnson, Stacey Abrams, Barack Obama, Vin Scully and Mike Trout are among those remembering baseball great Hank Aaron, who has died at 86.

“It’s a very positive identification for me,” he says. “You look back through baseball and you find yourself in good company. You find the Lou Gehrigs, Ted Williamses, Willie Mayses, Roy Campanellas, Willie McCoveys as well as the Ruths, Cobbs and Hornsbys.

“I’ve always felt driving in runs was a solid measure of your worth to the team. I know I used to feel embarrassed if I left runners on second or third with less than two out. I didn’t feel embarrassed if I didn’t get a home run in a time at bat, or even a hit, but I always felt ashamed to leave runners on. It’s like you defected on your responsibilities.

“You know, I always felt I could go out and bat .350 every year. You can do that, you know, and you drive in 50 or 60 runs. But I didn’t see that as my function. I was the Hammer. I wasn’t up there to keep a rally going, or get on base for the big guys, I was the big guy. I had to find a way to bring those runs in.”

He did. Nobody did it any better.

Henry did a lot of things better than anybody — homers, ribbies, total bases, extra-base hits. He will be remembered for all of them. But, if you had to single out one, Henry feels they might have picked the right one. An RBI trophy seems to sum up what Henry Aaron was all about. Not just a slugger, not just a hitter, not just a showman — a player.

As the game’s commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, said: “This is the first time in history the real meat-and-potatoes guy has been recognized.”

That was certainly what Henry Aaron was — a real meat-and-potatoes guy.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.