Getting to Be Too Much of a Good Thing

- Share via

In 1919, Babe Ruth hit 29 home runs. That was about 14% of the home runs the rest of the league hit that year. It was 19 more than his closest pursuer (George Sisler) and 17 more than the top slugger in the other league. It was also more than 10 of the 16 teams in the major leagues hit that year.

In 1920, Babe Ruth hit 54 home runs. That was more home runs than any other team in the league. In fact, it was more home runs than all but one other team in baseball (the Philadelphia Phillies had 54).

In 1921, Babe Ruth hit 59 home runs. Only two teams in the league hit more.

As late as 1927, when Babe hit his historic 60, that was more home runs than any other team in the league. That was about 16% of the home runs the rest of the league hit that year.

When you talked about “one-man teams,” you were talking about Ruth.

In 1938, Hank Greenberg hit 58 home runs. That was only about 7% of the number the rest of the league hit and not more than any team in the league.

In 1961, Roger Maris hit 61 home runs. For the record, that was only 4% of what the rest of the league hit and not even half of what most teams hit.

In 1907, there were 100 home runs hit in the American League. Last year, there were 2,290. This year, it sometimes seems as if there are that many hit a week. This season, there were 1,271 home runs hit by the end of June.

Babe Ruth, what have you done? John McGraw, where have you gone? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.

It’s raining baseballs out there. Just when we thought speed and daring and craft had made a comeback, here comes brute strength, stand-around-and-wait for-the-big-inning baseball.

Pitchers are afraid to let go of the ball. Outfielders are getting fence burns backing up for the long drives. The jokes are endless. If you grip the ball tight, you can hear its heart beating. If you run out of baseballs, just drop two of them in a bag and, presto, they’ll multiply.

Ruth’s record is going to be broken by some rookie right out of college. Maris’ record is going to be broken by so many guys they’re going to run out of asterisks.

What has happened? Well, it’s the ball, of course, some say. It’s atomic. It’s wound too tight.

No, others say, it’s the pitchers. It’s mass hysteria. They throw gopher balls out of panic.

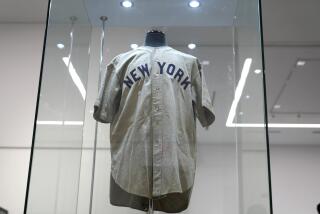

Babe Ruth put the home run in baseball. Before him, it was considered an aberration, not a true product of the game. A fluke--like a triple play.

The Babe wrested the game away from the Ty Cobbs and the John McGraws and the brand of the game now called mockingly, “Little Ball.” Ruth played Big Ball. The game before him had been a kind of bean-bag, hit-’em-where-they-ain’t exercise. The joke went that Babe hit-’em-where-they’ll-never-be.

The home run itself isn’t that exciting. It’s the anticipation of the home run that brings the fan to his feet, that sets his heart to pounding, his throat roaring.

It makes a three-run lead precarious. It makes a routine 4-1 game obsolete. In McGraw’s day, when a team went into the ninth inning leading by three, the game was over. In the day of the home run, it may have just begun. A walk, an error and a pitcher’s mistake and you have a tie game.

It’s not like a triple bounding around between fielders with the bases loaded, but the public likes it. Americans like the Big Game. Pitching duels are for the purists. Home runs are for the hard hats.

But has it gotten out of hand? Do we need a homer every other time at bat? Isn’t there something wrong when banjo hitters start hitting opposite-field home runs?

There was a period when the pendulum seemed to have been swinging the other way. First of all, there were the new ballparks. Round, symmetrical, protected from helpful currents of air, they offered none of the cheap home-run opportunities of the older, more eccentric ballparks whose geometric design had to be molded to fit existing city streets.

The new parks also had carpeted playing surfaces, which encouraged speed, base-running, base-stealing and the small skills that threatened to take the game back to its roots.

The American League was always the league with the big shoulders. With its legacy from Ruth, it scorned the small game, where you stored up runs like squirrels in winter, in favor of its big-inning theory of baseball.

So, the fans might like home runs--but a man might like ketchup, too. But not too much of it. Not to the point where it smothers the meat.

The art of any sport is constantly at odds with the science. You have to keep the man with the smock and the slide rule at bay. He has the power to wreck any game. Golf could make a ball--and a club to hit it with--that could carry 500 yards if it wanted to. Automobiles could go 500 m.p.h.--if you had robots driving them.

Do we want to turn ballplayers into bat-wielding robots? Baseballs into computerized projectiles? John McGraw once complained that the home run took the thinking out of baseball. Well, it might take the sport out of it. A game with nothing but home runs would be worse than one without any.

Baseball has always depended on the delicate balance between offense and defense. Today, it seems beleaguered by modern technology--artificial turf and artificially powered balls--which seems to be cheapening the stolen base and the home run.

Maybe it’s time to put a little sawdust back in baseballs and dirt back in infields. Before someone is moved to start writing, “Home run--as in ho hum.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.