THE DUCK STOPS HERE. . .

- Share via

If Walt Disney could see “DuckTales,” his reaction would eclipse Donald Duck’s most violent tantrums. Disney demanded--and got--better work from his artists in 1934, when Donald made his debut in “The Wise Little Hen.”

It’s not that “DuckTales”--premiering at 5 p.m. Monday on KTTV, Channel 11--is the worst cartoon series ever made, or even the worst of this season. After stinkers like “Hulk Hogan’s Rock and Wrestling,” it’s not even a runner-up.

It is a hugely disappointing series because viewers could legitimately approach it with the highest expectations. No one looks for top-quality animation or original stories on “Jayce and the Wheeled Warriors.”

But a program bearing the Disney imprimatur and featuring Donald Duck implies a certain standard of excellence. The Disney reputation was built on the unsurpassed animation of these characters, and “DuckTales” falls far short of that standard.

The reason is that, for the first time, a foreign studio (TMS, or Tokyo Movie Shinsha) has done classic Disney characters--Donald and his three nephews--in limited, Saturday morning-style animation. The idea seems almost sacrilegious.

When the Disney studio first began producing animation in Japan for the 1985 Saturday morning TV season, many animation fans regarded it as the betrayal of a tradition. There were angry mutterings that the new management team was planning to subdivide the Magic Kingdom into condos.

The high quality of the studio’s first programs, “The Wuzzles” and “Gummi Bears,” defused much of that anger. Although vastly inferior to traditional Disney animation, “Gummi Bears” featured some of the best work done for TV in recent years.

But “Gummi Bears” was a new, self-contained universe: Viewers had never seen Gruffi or Grammi Gummi and accepted their limited motions. Donald Duck is one of the most famous cartoon characters in the world, with a walk as distinctive as Charlie Chaplin’s.

Unlike the stiff, comic-book figures of Saturday morning kidvid, which are intended to look good when they’re not moving, Donald was designed to be animated. His body is constructed out of rounded forms that seem to flow from drawing to drawing. The Disney animators made every movement demonstrate his unique, volatile personality, from the swing of his arms in a temper tantrum to the shimmy of his plump rear end when he walked.

Although the medium is extremely popular in Japan, no tradition of full character animation exists there. The Japanese studios grind out dozens of features and TV shows for the domestic market but the animation itself is extremely limited: Some programs use as few as four drawings per second of screen time, where traditional Disney animation requires 24.

It is cheaper for American studios to ship the work out than to pay union wages here, but Disney Vice President of Television Animation Michael Webster and “DuckTales” associate producer Tom Ruzicka insisted that cost was not the determining factor in the decision to make “DuckTales” in Japan. (At $300,000 per episode, the budget for “DuckTales” is good, but not extraordinary.)

“When we started, the yen was at 240 to the dollar; it’s now at 143 to the dollar, so our costs went up 40% just through shifts in the currency,” said Webster. “It is not cheaper for us to do it over there. But they have a talent pool of fantastic draftsmen that we don’t. We have some talented artists over here, but nowhere near enough to handle the massive amounts of footage we need. And the work ethic in Japan is phenomenal: They all work six-day weeks, and probably at least 10-hour days. Some of them work all night. I’ve gone into the studio in the morning and seen guys sleeping under their desks--it’s unbelievable.”

Initially, “DuckTales” was supposed to be based on an extremely popular series of comic books by Carl Barks. A former animation story man, Barks took over “Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories” during the ‘40s and transformed Donald Duck into a caricature of a middle-class family man--and a reluctant hero. Fantastic adventures interrupted Donald’s attempts to cope with the mundane problems of daily life in suburbia.

The Duck and his nephews met Gu, the Abominable Snowman, while searching for the crown of Genghis Kahn in the Himalayas, fought a gigantic jellyfish for possession of the fabulous Candy-Striped Ruby in the South Pacific and discovered a lost Mayan city in Yucatan. To the Baby Boomers who grew up reading these comics, Barks’ Duckburg was as familiar as their hometown, yet as exotic as anything in “The Arabian Nights.”

The moving force behind these adventures was Barks’ most famous creation: Donald’s uncle, Scrooge McDuck, the world’s richest duck, whose fortune comprised “five cubic acres of money.” The old skinflint used Donald, Huey, Dewey and Louie as a source of cheap labor in his schemes to get even richer.

Barks also created the familiar characters of Gladstone Gander, Donald’s obnoxiously lucky cousin; Gyro Gearloose, a feather-brained inventor; the evil sorceress, Magica De Spell and the Beagle Boys, a gang of incompetent, identical thugs. “DuckTales” brings the entire cast to the screen, with some additions and more than a few changes.

“Barks was never really consulted,” Ruzicka said, “although the show was initially based on the concept of doing Scrooge McDuck and the nephews. We discovered that a lot of stuff that made wonderful comics wouldn’t translate into the ‘80s or into animation, so we started evolving new characters and other things to contemporize the show. As we did that, the stories got further and further away from the comics, although a few episodes are lifted right out of them.”

The biggest change is the frequent absence of Donald: He’s joined the Navy, and his role has been reduced to an occasional cameo. Huey, Dewey and Louie now play under the semi-watchful eye of their nanny, Mrs. Beakley, who’s so plump she looks like a duck-billed pillow. She brings her tag-along daughter, Webbigail--a sort of composite of Daisy’s old nieces, April, May and June--into the McDuck household.

This version of Uncle Scrooge is considerably more generous and kindly than he was in the comics. In the “Send in the Clones” episode, he casually gives his grand-nephews money for movie tickets, popcorn and new bicycles: The idea of giving away that much cash would have given the real Scrooge a coronary.

Although Ruzicka said that McDuck “wouldn’t be a very endearing character if all the depth he had was an interest in money,” Barks’ Scrooge was only interested in money. Readers happily followed his adventures for decades.

Everyone involved in the project stresses the originality of “DuckTales,” but the situations, the timing, the animation and many of the lines all seem very familiar. The comedy-adventure cartoon has been a standard of children’s programming since “Crusader Rabbit” (1949) and “Ruff and Reddy” (1957). “DuckTales’ ” “Sphinx for the Memories” episode is curiously reminiscent of Hanna-Barbera’s “Scooby-Doo, Where Are You.” You see familiar “scary” monsters moaning in familiar voices; the same chases with the villains falling into barrels.

But give “DuckTales” its chance. So far, the series has been exceptionally well-received by broadcasters and will premiere in 150 markets covering 93% of the country. Webster hopes to make additional episodes after the initial 65 have been shown, and is already planning another syndicated series for fall of 1989.

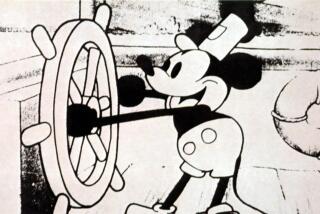

Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and the other Disney cartoon stars owe their popularity and longevity to the fact that they were so well animated they ceased to exist as drawings on the screen and emerged as clearly recognizable characters.

By breaking with that tradition in “DuckTales,” the new management at the Disney studio is risking far more than the $20 million it has invested in the series: At stake is a name that has been synonymous with the best in animation for 60 years.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.