The Legend of Jesse Unruh : A DISORDERLY HOUSE The Brown-Unruh Years in Sacramento <i> by James R. Mills (Heyday Books: $17.95; 213 pp.) </i>

- Share via

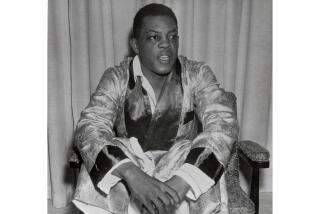

After scorning his leadership for the last 15 years of his life, Sacramento virtually deified Jesse M. Unruh upon his death Aug. 4, with politicians of both parties tumbling over each other to praise the fallen state treasurer. Republican Gov. George Deukmejian named State Office Building No. 1 after Unruh, but Democratic Assembly Speaker Willie Brown went a step further, placing within the 80-member chamber a shrine to Unruh, an 81st desk that, draped in black and forever vacant, mournfully awaits the return of Big Daddy.

Naturally, a strain of opportunism underscored Sacramento’s official sorrow, as speculation over the treasurer’s successor overtook reminiscences of the once-mighty Unruh. Still, for many who knew him when he ruled as Assembly speaker in the 1960s, Unruh’s death in relative obscurity capped two decades of lost opportunity. Unruh never became governor, and California was ruled instead by a succession of slicker but arguably shallower politicians.

And so, James R. Mills’ “A Disorderly House: The Brown-Unruh Years in Sacramento” reads not so much as a history but rather as a tragedy. Mills, a San Diego Democrat who would later become president pro tem of the state Senate, spent his first six years at the Capitol as an Unruh protege in the Assembly. The book is his lively memoir of the years 1961-66, when California’s Democrats, despite their control of both the Legislature and the governor’s mansion, foundered on the rivalry between Unruh and Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown for party rulership.

Told through the wide eyes of an idealistic, young assemblyman, “A Disorderly House” is a politician’s coming-of-age story. It begins with Mills taking the oath of office in January, 1961. He stands enraptured by the classical elegance of the Assembly chamber, only to find his political and aesthetic tempers joined in disgust to see the house ruled by Unruh, who seemed little but a corrupt, corpulent servant of special interests.

Mills had come to Sacramento intent on aiding the owlish, bespectacled Brown in his battles with Unruh, a 290-pound behemoth already known as Big Daddy for his appetites for the wine, women and song provided by lobbyists’ money. But soon after his arrival, Mills switches sides. Brown had excluded Mills from his confidence for what seemed arbitrary, political reasons. Big Daddy, however, appeared to recognize Mills’ intellect and integrity, and gradually welcomed him to his inner circle.

Soon thereafter, Mills comes to see that despite their public reputations, it is Unruh rather than Brown who is responsible for the progressive legislation of the day. From then on, he commits himself to Unruh as the Speaker advances his liberal goals and expands the power of the Legislature.

As a memoir, “A Disorderly House” makes no claim to objectivity. Sketches of characters are telling but often superficial, and Mills frequently oversimplifies issues into what seem to him obvious matters of right (Unruh) and wrong (everybody else).

But in exchange for scholarly detachment, Mills offers the passion of a participant. He casts the battle between Unruh and Brown in heady, even mythic terms. The Speaker emerges as a figure of legend, alternately described as a Lincoln, a Caesar and even a King David. Brown appears as a petty, perfidious nincompoop who mistakenly sees his greatest enemy in the Speaker. Brown’s machinations succeed in foiling Unruh, but it is a Pyrrhic victory that cripples the party and delivers California into the unworthiest hands of all--those of Ronald Reagan.

Although it rings with disappointment at the end, “A Disorderly House” is far from an angry book. Throughout there is a sense of reflective self-mockery; nostalgic rather than embittered, Mills recalls those days with a sense of joy. He doesn’t argue Unruh’s liberal agenda, for he takes as a given that all would support such goals as civil rights, consumer protection and aid for the aged.

Looking back, Mills sees the days of Unruh’s ascendance as an adventure of Arthurian proportions. In this Sacramento Camelot, Unruh was “the most heroic of all,” and Mills was one of that “trusty band of companions who loved to join him in doing battle with the forces of darkness and in coming to the aid of the friendless and afflicted, just as they loved to join him in eating and drinking at tables round.”

But like all heroes of classical drama, Unruh had his flaw; for one hubristic act, Unruh would pay for the rest of his career. It came on July 30, 1963, when the Speaker, enraged at Assembly Republicans for their refusal to vote on the state budget until they saw the text of a school finance measure, locked the minority members in the chamber for 23 hours.

The action tarred Unruh as a tyrant; forever, wrote the San Francisco Chronicle, Unruh would stand “revealed for what he is--a crude political adventurer out to gain totalitarian control . . ..”

To Mills, Unruh locked up the Republicans for the same reason he did anything: because it was right. And because of his courage and candor, Unruh suffered. His enemies--the Brown Administration and the Republicans--exploited Unruh’s unflattering image, portraying him as an amoral despot when in reality he was the most righteous of them all.

For Mills, the tragedy is that Unruh never became governor. Brown rather than Unruh was the Democratic nominee in 1966, and his misfiring campaign sent Ronald Reagan to the Capitol, condemning California to “a dark age of lowered expectations.” Unruh’s fortunes faded as the 1960s wore on. After losing races for governor and Los Angeles mayor, he was able only to capture the ministerial office of state treasurer, where he remained from 1974 until his death last summer.

In an epilogue added after Unruh’s death at age 64, Mills writes that Unruh ennobled every office he held, whether as a legislator or as treasurer. “In whatever role he appeared, there was a Shakespearean dimension to him,” he concludes. In “A Disorderly House,” Big Daddy is remembered as one that led not wisely, but too well.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.