Paton Dies; Alerted World to S. African Blacks’ Plight

- Share via

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — Alan Paton, the elder statesman of white liberalism in South Africa whose 1948 novel, “Cry, the Beloved Country,” awakened the world to the plight of blacks here and won instant and lasting acclaim, died this morning at the age of 85.

Paton had been ill for about three weeks, suffering from inoperable throat cancer, according to his wife, Anne Paton. He died at his home in Botha’s Hill, in the lush, rolling countryside of Natal province near Durban.

A vigorous writer, lecturer and political philosopher, Paton seemed ageless in his energy. When he turned 85 in January, he still had a shock of thick white hair and had just finished the second part of his autobiography, “Journey Continued,” and he still made a few public appearances.

He said it would be his last book. “When one has spent 84 years as a workaholic, one is entitled to become a dropout,” he said at the time.

The son of strict Scottish immigrants in Natal province, Paton was working as a schoolteacher in 1935 when he was appointed principal of Diepkloof Reformatory, a school for black juvenile delinquents near Johannesburg. It was there that his education in race relations in South Africa began.

Twelve years later, on a tour of prisons and reformatories in Europe and the United States, he began a book while sitting in a hotel room in Norway. Filled with “an intense homesickness for my wife and sons and my far-off country” and a powerful anger for the injustice there, he said years later, he sat down and wrote these words:

“There is a lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hills are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond any singing of it.”

Held for Murder of White

And so began “Cry, the Beloved Country,” the tale of an aging black country pastor whose son is arrested for the murder of a white man in a country where Afrikaner nationalism was growing.

Published by Scribner’s Sons, under the tutelage of the respected editor Maxwell Perkins, “Cry, the Beloved Country” became an international best-seller. It has been translated into 17 languages and sold nearly 17 million copies. In some classrooms across the world, including the United States and South Africa, it remains required reading.

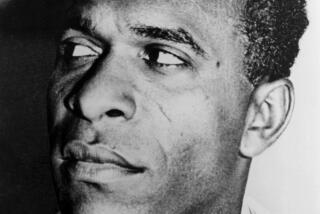

A play and a film, starring Sidney Poitier, were made from the book.

At the premiere of the film, Paton sat next the wife of D. F. Malan, then prime minister of South Africa. Paton described her reaction years later in his autobiography, “Towards the Mountain”:

“She was clearly disturbed and said to me, ‘Surely, Mr. Paton, you don’t really think things are like that.’ I said to her: ‘Madam, I lived in that world for 13 years,’ but I did not add, ‘and you, madam, have never seen anything of it at all.’ ”

More than any other book, “Cry, the Beloved Country” brought the story of apartheid in South Africa to the world. It has been called the single most important literary contribution in the international anti-apartheid movement.

After the book appeared, Paton quit his job at the reformatory and went on to write three novels, a biography and a half-dozen histories, none nearly as popular as his first work.

In 1953, he helped found the multiracial Liberal Party in South Africa and became a contentious critic of the ruling National Party. His passport was confiscated in 1960 and wasn’t returned for 10 years.

The government banned multiracial parties in 1968, and the Liberal Party, rather than kick out its nonwhite members, was dissolved. Paton left politics then, turning again to lectures and writing, and the government left him alone.

Opposed Sanctions

Once considered among the most left-wing of all white South Africans, Paton’s views had been considered too moderate by many liberals in more recent years. He looked kindly on the step-by-step reform process instituted here by President Pieter W. Botha and opposed international sanctions against Pretoria, arguing that outside pressure would have no effect on the pace of government reforms. Paton also considered the idea of one man, one vote for this country “pie in the sky.”

In South Africa, the government is controlled by the white minority, with a population of 5 million, while the 26 million blacks in the country have no vote in national affairs.

Although he once described South Africa as “a country where you hope on Monday and despair on Tuesday,” Paton remained an abiding optimist for his beloved country.

In December, he wrote an assessment of the political developments in 1987 for a South African newspaper. “I don’t believe reform is dead, or even dying. But it is certainly very lethargic,” he wrote.

He saw the situation in South Africa as one of whites “searching for ways to undo their conquest” and blacks doing the same. “The magnitude of the task is impossible to exaggerate,” he said.

Earlier this year, Paton told a local newspaper that he worried that one particular passage of “Cry, the Beloved Country” might be prophetic.

In that closing passage, the Zulu clergyman, Theophilus Msimangu, who the narrator says “had no hate for any man,” confesses: “I have one great fear in my heart, that one day when they turn to loving they will find we are turned to hating.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.