Path of Pain : Former Cal State cager Roger Coleman battles the years, his own body and the depths of exhaustion to succeed as a bicycle racer. ‘Sometimes,’ he says of training, ‘you just have to make it hurt.’

- Share via

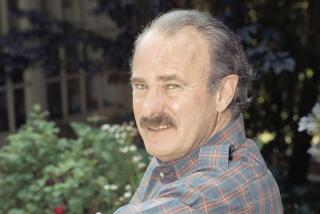

He is a lonely figure in the distance pedaling across barren, muddy fields at Cal State Dominguez Hills.

Long legs straddle a 2-wheel racing machine. Roger Coleman keeps his eyes on the ground.

Dull gray overcast provides a stark backdrop to Coleman’s bright red sweat shirt and pants. It is misting. Later it will turn to rain.

An athletic training major, the 170-pound blond once scored points for the Toro basketball team. Now he is trying to score points for himself. He is training for the road racing season, where he hopes to find a sponsor or earn a spot on a racing team.

It is a lonely, arduous life aboard his racing bike.

Coleman pedaled 16 miles from his Bell home to Dominguez Hills. Soon he’ll rejoin the bike trail along the Los Angeles River, ride it to the Queen Mary in Long Beach, cruise the sand to Belmont Shore. As the mist thickens and the horizon dims, he will ride home, an additional 30 miles, along a bike trail that follows the San Gabriel River.

“There are days when you are just out there and you can take in the scenery,” he said. “Then there are the days when I am training, when I go from Bell (to) here and I can’t tell you what took place along the way.”

Those are the days that Coleman simultaneously loathes and loves. It is racing bicyclists’ paradox, a sadomasochistic ritual that pushes bodies beyond their limits. The threshold where lactic acid buildup in muscle tissue brings on fatigue and blackouts is what Coleman refers to as “the pain zone.”

“Sometimes,” he says, “you just have to make it hurt.”

It is a philosophy recreational bicyclists do not understand, he said.

“The more pain you endure in riding, the better off you will be.”

Listening to the 6-foot-6 former Bell High School basketball star describe his ritual draws a few winces.

There was the time he blacked out on a scorching 110-mile ride up a mountain road to Crystal Lake. He has been attacked by youth gangs on secluded river trails. When his old car broke down in September, he took to the bike trails for transportation to Dominguez Hills.

The Los Angeles River trail attracts truants, and they have pelted him with rocks as he sped by. He points to scars on his left elbow, where he has been clipped numerous times by the side-view mirrors of big-rig trucks as he rode along busy Florence Avenue near his home.

Coleman shrugs off these events as “the monotony of riding every day.” There are bike trails he claims to have ridden so often that he has “worn a hole in the center of them.”

He likes the river trails, despite “the hoodlums.” They can be dark and dank, but they are lifelines away from the seedy decay he sees in Bell.

One of five children, Coleman used to think that his hometown “was the sweetest little city you can have.”

“Over the years, though,” he went on, “the life there has corroded.”

Coleman’s neighborhood has become “Miami Vice every night.” He has watched drug deals and prostitutes. His tuition money was stolen from his home.

The family put up security bars. Though his neighborhood is not a slum, it is “a rough part of town. If I could, I’d move out of there and take my parents with me.”

Coleman hopes that his bicycle can help show him find a way to leave, although at 25, he is considered beyond the peak years for cyclists.

Still, he aims to “ride the coattails,” of his younger brother Tim, 20, who is considered a top road-racing prospect.

Roger Coleman was an all-Eastern League basketball player in 1981. But scholarship offers for an inner-city white center didn’t materialize.

He attended Cerritos College and tried to play basketball there. A knee problem slowed him down. He went on a weight-lifting program and ballooned to 195 pounds. He became sluggish.

“By the end of the season, I could not touch the rim,” he said.

Coleman, a part-time player, quit the team at Cerritos but continued to play in off-season leagues. Dominguez Hills Coach Dave Yanai saw Coleman play in a spring league, and in the fall of 1982, Coleman accepted a scholarship to play at Dominguez Hills.

Two years later Coleman, still a part-time player, quit basketball again, this time to take up road cycling and concentrate on his education. Another two years passed. Then, last year, as classes began, Coleman had a change of heart . . . again. He approached Yanai about returning to play in his final year of eligibility.

“I saw Coach. I saw the team he had,” Coleman said of a group that finished 13-13. “I could see he had a team of guards. His recruiting had not come through. I have a lot of respect for the man. I had one year of eligibility left.”

There was no scholarship money left, but Coleman walked on anyway and became an instant starter.

Still, he averaged only 6.5 points and 4 rebounds a game. Yanai asked Coleman to cut back on his cycling, and Coleman agreed. But there were Sunday mornings, after Saturday night games, when Coleman would mount his bicycle and head off for Laguna Beach or Palos Verdes.

Coleman would like to race for the U.S. Cycling Team, but he realizes that “is a lofty goal.”

“I’m 25 years old,” he said. “It’s not like I can’t do it.”

To do it, however, training is crucial. Over two plates of pasta and marinara sauce, dinner rolls without butter and fresh fruit, Coleman described the importance of eating correctly. He often “carbo loads” on pasta.

“My mom hates it,” he says. “She says, ‘What are you going to have for dinner tonight, Roger, pasta?’ That’s all I eat, and I’m a guy that grew up in a home where every night you ate steak for dinner.”

Testing in an exercise physiology class taught him that he should eat a minimum of 6,000 calories a day during training. He figures he can gain about a pound a week if he bumps that up to around 8,000 calories a day.

Extra poundage would hurt him, however. He is taller than most competitive cyclists, and he already outweighs most of them. He can’t afford more drag than his lanky body already provides.

So Coleman forces pasta into his stomach, then stomachs the pain as he approaches another performance threshold.

“I enjoy making my body perform at its limit. Cycling is the only thing that comes close to it,” he said.

Coleman works odd jobs to make what little money he can. Racing takes much of his time, and without a car, he can’t get everywhere on his bicycle. He was interested in several part-time training jobs, but he needed reliable transportation. At best, he says, he can maintain a 25-m.p.h. pace on the road with his bike, and that is not reliable enough.

His social life is also on hold.

“You don’t date much when you don’t have money,” he said. “But I don’t spend much. Just a little on my bicycle now and then, a tire or something.”

Roger and Tim live with their parents and a younger sister. An older sister is helping Roger buy a new engine for his car. Coleman hopes to install it soon.

But his mind is on his bicycle, which is like an old friend by now.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.