MOVIE REVIEWS : Rossellini and Danson Pair in Americanized Version of ‘Cousins’

- Share via

To add to the long list of translations from the French, we now have our American “Cousins” (citywide), which began as 1975’s vastly successful “Cousin, Cousine.” As directed by Joel Schumacher, what moments of genuine emotion “Cousins” has can be traced directly to Isabella Rossellini; the rest is bustling, prettified, thoroughly bogus but intermittently entertaining.

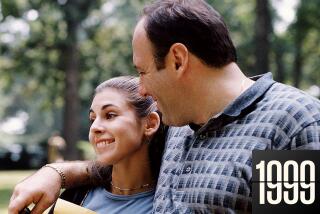

It traces a tender friendship that begins between a couple (Isabella Rossellini and Ted Danson) with nothing initially in common other than the fact that their respective spouses (car salesman William Petersen and cosmetics demonstrator Sean Young) have begun a very public affair. It ignites during the raucous second marriage celebration of Rossellini’s mother (Norma Aleandro) to Danson’s uncle, and at frequent intervals thereafter.

Danson, who drives a motorcycle with a sidecar in preference to a car, is supposed to be charmingly irresponsible about the material world. At present, he has a job as a dance instructor; in the past he’s been an investment banker and a trumpeter in a jazz band. Rossellini, who works as a legal secretary, seems bemused but not particularly disturbed by this thoroughly out-of-step original.

Their partners’ deceptions hurt them both: Danson takes refuge in an attitude that everyone has a right to freedom of choice; in Rossellini’s case, the wound is clearly not a new one. She has chosen to overlook Petersen’s countless affairs in the past because of their little daughter. It’s only when an almost inadvertent (and charmingly written) affection grows between her and Danson that she wakes up to the real emptiness of her life.

“Cousins” has a palpable glow when Rossellini is on the screen, radiating a charm and a pure inviolable honesty that will make you think of only one other actress: her mother, Ingrid Bergman. It’s an aura that spills over to include co-star Danson in its warmth. In their presence you will a lot to work that might, frankly, founder in other hands.

What makes “Cousins” feel splintered is that while so much of it is delicately written, there is also a jarring crassness at times, sure-fire cuteness, “boffo lines” or characters, like fake-wood siding tacked on to a beautifully constructed house.

Since these embarrassments come on the heels of deftly funny lines (like Rossellini’s and Danson’s deadpan zingers when Petersen brings Young back to the wedding site hours late), it’s a peculiar mix. It’s hard to know from simply scanning the credits where the problem lies. Usually it’s with platoons of writers, but in this case, only one screenwriter is credited, playwright Stephen Metcalfe, whose first produced screenplay this is.

Yet Metcalfe has solved the original film’s toughest story problem: how to keep from feeling real pity for the Sean Young character, who was a ditz and a neurotic, but clearly undeserving of the pain inflicted on her. In “Cousin, Cousine,” it was easy to dislike her paramour, the compulsively straying husband, and to feel that he was getting what he deserved, but at some point, the flaunted infidelity of the “wronged” couple (our Danson-Rossellini pair) felt too insensitive, even for the romantically tolerent French.

This screenplay gets around our queasy feelings of cruelty by strengthening Young’s character (nicely played) and by the very gently dawning affection between the odd couple out. Rossellini’s character, with 12 years of marriage behind her, is clearly struggling with moral reservations about dashing into a love affair, and Danson, who has never crossed this line of infidelity before, is in love with her when he finally does. This delicacy of writing and performance is the film’s real plus.

But “Cousins” has its exasperating side too: ersatz ethnicity (to these film makers there are no differences between Italians and Argentines, and a cartoon sense of what a real Italian wedding feels like); the broad obnoxiousness of Danson’s teen-age son (Keith Coogan) and marriages and remarriages that have been made entirely too symmetrical. When Lloyd Bridges as Danson’s father enters the picture with his blunt aphorisms, it’s far too pat to team him up with Aleandro. (The French didn’t push that in “Cousin, Cousine”: Mama sampled what this new widower had to offer, found it wanting and settled for her freedom. Why must tidiness be such a besetting American trait?)

“Cousins” (rated PG-13 for the decorousness of its love scenes) is such a patent fairy tale that it’s impossible to guess in what city or even which part of the country it’s supposed to take place. From the scenery you’d say Colorado/France/Switzerland, although it was shot in British Columbia. It’s no wonder the “Italian” part of its ethnicity comes with all the authenticity of a Chef Boy-Ar-Dee boxed dinner. By the movie’s last, satiric slapstick quarter, in which all production stops are pulled at a nuptial extravaganza palace called Wedding Land, its style has undergone another wrenching change. It remains only for that smarmy, home-movie tableau at the close to signal “Cousins’ ” final bankruptcy.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.