Khomeini Discolors Vision of One World

- Share via

As an incurable optimist (of sorts), I agree that nothing in this world is so bad that some good may not come of it. As evidence, I offer the publication history of Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses.”

The behavior of the Ayatollah Khomeini was outrageous. For an Iranian religious leader to post a $5-million reward for the murder of an author living outside his own country was, to put it mildly, arrogant effrontery. He invited terrorism; he was attacking free speech.

But closely examined, this development throws light on a longstanding dispute about the desirability of One World, a single world state. The roots of this dream go back to the 4th Century B.C., when the philosopher Diogenes proclaimed himself a “cosmopolite,” a citizen of the world. In the 20th Century, Diogenes’ ideal went public with the formation of the League of Nations in 1919, followed by the United Nations in 1945. Today, a liberal is often judged by the enthusiasm he brings to the struggle to create One World, a world governed by the same standard of behaviors everywhere, a world without borders.

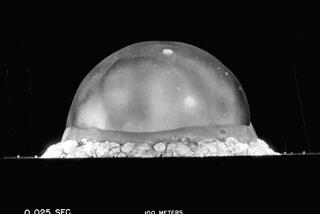

The cosmopolitan sentiment spread more widely when the appalling potential of a nuclear holocaust became undeniable. Surely, many said, we must unite or die. This is a plausible conclusion, but is political evolution taking place in that direction? It seems doubtful. True, the European Economic Community may go into high gear in 1992, but then again it may not. Since 1945 several of the world’s nations have split, but none have combined.

But suppose One World could be achieved; would it have any disadvantages? One, at least, is clear: the undermining of free speech brought about by the disappearance of borders. History makes the relationship clear.

The novel “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” by Englishman D.H. Lawrence was first published privately in Italy. “Ulysses” by Irishman James Joyce first saw the light of day in France. And now Salman Rushdie, raised as a Muslim in India, has brought out his “Satanic Verses” in the non-Muslim countries of England and America. These works vary in merit, but all were born into controversy, and without the option of foreign publication they might have been stillborn. Free speech is never worldwide.

The classic defense of free speech was given more than three centuries ago by John Milton: Let Truth and Falsehood grapple, for “who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?” At no time are all of any society’s beliefs correct. To improve itself--to move further from error and closer to truth--a society must have the guts to allow crackpots to expose their thoughts to criticism. Now and then a crackpot is right: This is the justification of free speech.

Would there be free speech in One World? A priori one might argue that freedom would flourish: Surely a minority that opposed a particular view would have too little power? Not so. Undoubtedly only a minority opposed the works of Lawrence and Joyce, but they prevented publication on the home turf. In each instance, a minority brought passion to the controversy, and passionate people are awfully good at grabbing the reins of power.

Khomeini has given us a taste of what would happen to free speech in a world without borders. He has tried to impose his standard of blasphemy on the entire world. One World would be a monster ruled by innumerable such passionate minorities. The activities of the would-be One World that we call the United Nations are already hobbled by minority interests. When a bureaucrat in the secretary general’s office was asked what archivist kept track of U.N. history, he laughed. “There is no historian at the United Nations, because no two members here could possibly agree on what has happened.”

One World could not protect intellectual works against passionate minorities, and there would be nowhere else to go. Progress would give way to paralysis and a degeneration of the spirit of inquiry.

The poet W.B. Yeats has taken the measure of dreamers: The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity. We would all be thankful to Rushdie and Khomeini for unwittingly reminding us of this deep and tragic truth. To keep Truth bubbling somewhere in this turbulent world, we will always need many separate nations.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.