The Triumph of Monkey Business : TRIPMASTER MONKEY His Fake Book <i> by Maxine Hong Kingston (Alfred A. Knopf: $19.95; 339 pp.)</i>

- Share via

“Got no money. Got no home. Got story,” says Wittman Ah Sing in this fantastic novel by Maxine Hong Kingston.

Ah Sing is an unemployed writer who encounters the ‘60s on a cultural rebound, a Chinese American determined to complete an ancestral Gold Mountain trunk with his wild stories. “I can’t die until I fill it with poems and play-acts.” He lives in San Francisco as a splendid incarnation of the Monkey King from the popular 16th-Century fiction, “The Journey to the West.”

Kingston is the author of “The Woman Warrior,” which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and “China Men,” winner of the National Book Award for nonfiction. “Tripmaster Monkey” is her first novel, an eminent brush with a wild romancer.

The Monkey King is the paramount metaphor in these stories; the simian moves are comic transformations, rather than mere imposture. Ah Sing creates the scenes, directs the action and conversations; the author and narrator are obscure mediators in this urban trickster crusade. For instance, the unnamed narrator says to a woman in a restaurant, “Are you the one I can tell my whole life to?” Such narrative intercessions are comic duels; the narrator is the second and the mind monkey the duelist in a dramatic remembrance.

C. T. Hsia in “The Classic Chinese Novel” wrote that Monkey King is “always the spirit of mischief when he is in command of a situation.” His sense of humor “implies his ultimate transcendance of all human desires . . . comedy mediates between myth and allegory.”

The author mediates cultural myths and identities, the political allegories of the ‘60s, and comic themes from classical literature. This new monkey would overturn the world with his coarse beard and bizarre clothes; at least he could enchant women with his imagination. “This is The Journey In the West,” said Ah Sing. “We have the eyes that won the West.” Those “little squinny eyes” that scan the plains at high noon.

Ah Sing marries to avoid the war in Vietnam and then stages the War of the Three Kingdoms in a theater. “Our monkey, master of change,” said the narrator, “staged a fake war, which might very well be displacing some real war.”

Anthony C. Yu, in his translation of “The Journey to the West,” noted that the classical monkey teaches enlightenment, “not simply the illusory nature of experience.” Wittman is a postmodern monkey, a philosopher of coincidence: “Do the right thing by whoever crosses your path.”

This monkey measured his mythic origins on stage, when “one big light blasted me.” Zeppelin Ah Sing, his father, was a theater electrician, and later, a gold miner; his aunties were showgirls. “I was a mad baby from the start . . . a descendant of free spirits.”

Even his surname is a dose of heart gossip from the trunk. People pause at names, ah, “but our family writes ours down.” Wittman explained that an ancestor responded to a schoolmarm, “Ah Sing, ma’am.”

Ah Sing is no moral master, but he is a resplendent commentator on scenes from cinema; in fact, there is more filmic hearsay than allusion to popular memories or political histories of the time. The cinema in this novel could be scanned as a revelation, the new dharma, a revision of classical scriptures. “You know that broken wind-up monkey in the gutter that James Dean covered with his red jacket in ‘Rebel Without a Cause’? We sell them, I wound one up, and put it on top of a Barbie doll.”

When the author encroaches on the narrative she can be hilarious: “Gary Snyder had gone to Japan to meditate for years, and could now spend five minutes in the same room with his mother.” However, some intrusions are unsuitable, the diction awkward: “Anybody American who really imagines Asia feels the loneliness of the U.S.A. and suffers from the distances human beings are apart.”

There is a wild humor and moral distance in the stories; coincidence seems to hinder the characters at times. The narrator bares the ironies in language, but seldom the intimacies; for instance, “Wittman’s English better than his Chinese, and PoPo’s Chinese better than her English, you would think that they weren’t understanding each other. But the best way to talk to someone of another language is at the top of your intelligence, not to slow down or to shout or to talk babytalk. You say more than enough, o.d. your listener, give her plenty to choose from. She will get more of it than you can say.” PoPo is his grandmother.

Ah Sing carries “The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge” by Rainer Maria Rilke; he reads out loud on a bus. Later, the narrator quotes from the prose poems: “He should shut them up with Rilke: It will be difficult to persuade me that the story of the Prodigal Son is not the legend of him who did not want to be loved. “ Indeed, the mind monkey is a contradiction; he is a comic trope, communal in imagination, but separated from histories, the ‘60s, and familial sentimentalism. “O King of Monkeys, help me in this Land of Women,” said the narrator. “He wasn’t crazy, he was a monkey.”

Ah Hong Kingston, she got great stories. Enchanted stories that could fill a trunk.

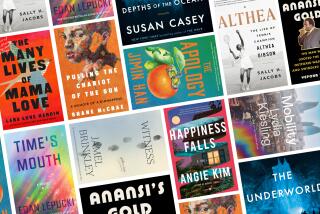

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.