Oldies but Goodies : Jukebox Turns 100 and Brings Back Memories of Old-Time Rock ‘n’ Roll

- Share via

WAYNE, N. J. — Clink. Charley Hummel drops a nickel into the jukebox.

Plonk. He taps C-1.

Whir. The platter twists onto the turntable.

WHAM! It’s 1958 and--great balls of fire!--Jerry Lee Lewis is on the loose:

You shake my nerves and you rattle my brain!

Too much loving drives a man insane!

You took my will! Oh what a thrill!

Goodness gracious, great balls of fire!

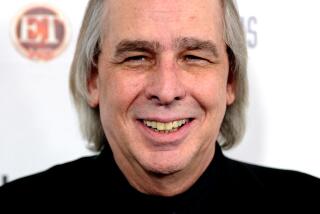

Hummel, an ex-cop with a ruddy, boyish face, stares fondly at his 1961 Rock-Ola Regis 200, which has the sleek chrome lines of a ’57 Chevy.

For a moment, he is transported back to his junior year of high school: The gang is together at the neighborhood bowling alley.

Then he snaps back. And, while “the Killer” wreaks aural havoc from behind the Rock-Ola’s blue metal grill, Hummel discusses the 100th birthday of that most American of inventions, the jukebox.

Hummel, an amateur historian, professional tinkerer and jukebox wizard, has determined that the first jukebox swallowed its first coin on Nov. 23, 1889, at the Palais Royale Saloon in San Francisco.

It didn’t much resemble its flashy descendants, nor did it have the same name--it was called a “nickel-in-the-slot.”

But the operating principle was pretty much the same: When a nickel was dropped into a slot, a wax cylinder began to spin, a needle dropped onto it, and music blared into crude headphones.

The songs were about two minutes long, and there was only one selection per machine. But it was recorded music, and the sound quality was surprisingly good.

Hummel collects jukeboxes, and the family room of his suburban home is a combination warehouse, workshop and museum, crammed wall to wall with vintage jukeboxes, wax cylinders, 78- and 45-r.p.m. records, advertising signs and a bronze bust of the father of recorded music, Thomas A. Edison.

The collection includes a turn-of-the-century nickel-in-the-slot that still works when a penny is dropped in (prices were slashed from a nickel in the 1890s).

After slipping in a penny, Hummel hands over the headphones and a listener hears the imperial strains of “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean” screech through the rubber tubes.

“It’s beyond our age--we really can’t recall these--but these are really dynamite pieces, these early nickel-in-the-slots,” Hummel says. “People couldn’t afford a phonograph, yet, for a nickel, they could go out to a tavern or an arcade and settle into a nice song they remembered.”

Elvis hadn’t been born yet, so 19th-Century hit makers made do with what was available. One early favorite: “Nearer My God to Thee.”

The word jukebox apparently entered the language in the 1920s. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language traces it to “jukehouse,” a Southern dialect word for brothel, which in turn came from a West African word dzugu , meaning “wicked.”

Americans embraced the machines.

The modern jukebox was born in 1927, when Automatic Music Instrument Co. made a machine that had amplified sound and played a variety of selections. It looked like an old wooden radio--but it set the stage for the heyday of the jukebox in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s.

Those were the years when Wurlitzer, Seeburg, Rock-Ola and other companies competed to create the most multicolored and spectacular jukeboxes imaginable.

Jukeboxes became an integral part of the American experience--particularly the experience of teen-agers flush with burgers and the first stirrings of romance.

It was a time when Perry Como crooned:

All your lunchtime money goes down the slot,

You could live on air if the music’s hot....

Jukebox baby, you’re the swingingest doll in town.

Jukeboxes hit an artistic peak in the postwar years, when Wurlitzer came out with its Model 1015, regarded by many aficionados as the most beautiful jukebox of all time. It was wrapped in a rainbow of multicolored plastic tubing, was trimmed with pieces of Art Deco chrome, played 24 songs and sounded sublime. It was an American classic.

“The war was over, there were happy times,” said Don Fairchild, who runs the Juke Box Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. “Money was more plentiful, jobs were opening up and people were getting out and listening to the jukeboxes.”

And along came something else: rock ‘n’ roll.

It’s no coincidence that the most popular jukeboxes at Fairchild’s hall of fame are those that were in use during the ‘50s. It was a golden age, when music and machine united in a marriage made in teen-age heaven.

Fairchild recalls growing up in Tishomingo, Okla., during the ‘50s.

“If you was going with a girl, it seemed like the songs they had back then--it seemed like every song was written about you and that girl. All them by Elvis, Fats Domino doing ‘Blueberry Hill’ . . . the Coasters doing ‘Searchin’ and ‘Young Blood.’ Whoo! They had some good artists back then!”

Charley Hummel remembers, too.

“I mean, God, I can remember the ‘50s. We used to listen to Elvis all the time on the jukebox--it was super--and . . . the Penguins, Clyde McPhatter, the Tokens . . . a lot of those R&B; songs, we used to blast them.

“Normally, kids weren’t supposed to know where the volume control was, but we all knew where it was in the back, and you just took your little screwdriver and you just slowly, slowly cranked it up.”

To demonstrate, Hummel leans behind his 1961 Rock-Ola and makes an adjustment, then slips a coin in the slot. A drum beat sounds and Chubby Checker blasts out a song from the year the jukebox was built:

Come on, let’s twist again like we did last summer, Let’s twist again like we did last year, Remember when we were really hummin’. Yeah, let’s twist again, twistin’ time is here.

That was one of the last good years for the jukebox industry. The industry estimates that 43,000 new jukeboxes were shipped to customers in 1955 and 42,000 in 1960. By 1965, the numbers had slipped to 29,000; by 1975, 17,000; and by the mid-’80s, 10,000 to 12,000.

Jukeboxes were challenged by home stereos, shunned by fast-food drive-ins and threatened with obsolescence by the compact disc and the decline of the 45-rpm single.

There’s been a modest revival in the last few years. In part, the industry has adapted, producing jukeboxes that play CDs and music videos. In part, it is because people yearn for the old times and are buying nostalgic recreations of the old jukeboxes.

“I would say it is going to continue to increase because you are incorporating new technologies into it, which is attracting new audiences,” says Fred Newton of the Chicago-based Amusement & Music Operators Assn., a trade group. “The oldies’ thing is going to continue.”

Not surprisingly, Hummel is bullish as well.

“I think there is a market, especially for the CDs. The CDs are high quality and high-tech. That’s what the public wants; they want good music. And that’s what the jukebox has been doing for 100 years--it’s been getting better quality, better sound and better reliability. So there is a place for the CDs.”

Still, he says, he hopes the record industry continues to produce 45s.

As he speaks, Hummel drops another nickel into his jukebox. “This is one of my favorites,” he says. “Percy Faith. ‘Theme From a Summer Place.’ ”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.